This article is produced and financed by the Institute of Marine Research - read more

Bluefin tuna are hard to catch – marine scientists want to help

Hard to catch, may overheat and can’t cope with rough seas – those are just a few of the challenges for fishers targeting the world’s biggest tuna.

This year’s Norwegian fishery for bluefin tuna is over, with only around a quarter of the 239-tonne quota caught. Many fishers have little to show for their work.

Fish capture researcher Manu Sistiaga boarded the purse seiner "Vibeke Helene" to document the fishery and learn about the challenges involved. The aim is to help overcome them through research and development.

Fish on the surface are harder to catch

The fishing expedition started in Måløy at the end of September and covered the area between Værlandet and Sandsøya island. It didn’t take long for them to find some fish, which in itself can be difficult.

“The fishers find that fish which appear on the surface move very quickly. It is mainly fish that they locate with sonar that they are able to encirle and catch in their nets”, says Sistiaga.

He witnessed four unsuccessful casts where the fish escaped from the net and two successful ones. With their first cast, the crew caught 24 bluefin tuna weighting an average of around 230 kilos. The following day they caught 29 tuna with an average weight of 260 kilos.

Carefully laid on a carpet

It isn’t easy to ensure that the meat of the fish retains its high quality, but the quality affects the price obtained by the fishers.

“The fishers pull the net closed and lift the tuna onboard individually onto a thick carpet. That is to avoid damaging their skin. The fish are bled and then subjected to the Japanese ikejime technique”, says Sistiaga.

Ikejime involves threading a steel wire into the spine of the fish to destroy their central nervous system. This causes its muscles to relax and means that it doesn’t produce lactic acid. Rigor mortis is postponed.

“I was impressed by the efficiency of the fishers”, he adds.

Must be cooled quickly to avoid overheating

The fish are then put into a cooling tank. Bluefin tuna need to be cooled down quickly.

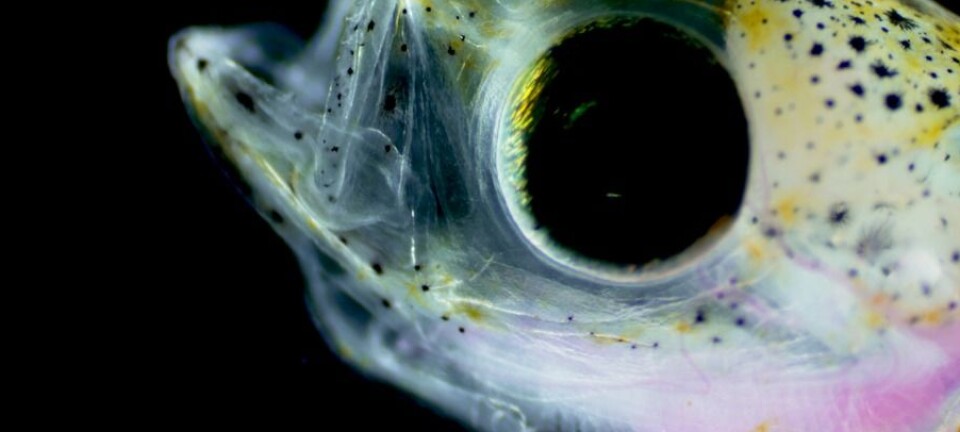

This massive tuna can dive up to one thousand metres and has the entire Atlantic ocean as its playpen. In order to cope with such varied environments, it has an incredibly fast metabolism and a higher body temperature than its surroundings. A bit like a warmblood horse.

“When the fish suffers stress and is taken out of the cooling sea water, there is a risk of it overheating, and of the meat basically being ‘cooked’. At the landing facility, specialists take a sample of the meat before giving it a quality score”, explains Sistiaga.

Can’t cope with rough seas

Once the fishers have the fish in the cooling tank, the key is to avoid rough seas.

“Bluefin tuna cope very badly with rolling. Their skin turns white and their market value falls”, says Sistiaga.

He has noted down his experiences from the trip and his impressions of the fishers’ needs:

- The fishers want greater sharing of knowledge, experiences and equipment between vessels.

- The ICCAT inspector present thought that the Norwegian boats needed to sail faster to surround the fish and avoid unsuccessful casts. In the Mediterranean, vessels targeting tuna travel at 10 knots, as opposed to 7-8 knots here.

- The inspector also considered that it would be better to use a boat than a sea anchor to stretch the purse seine backwards.

- The fishers on Vibeke Helene felt that the tuna nets from the 1970s are not suited to modern vessels and fisheries, and wanted greater cooperation on coming up with modern designs. Their equipment is a big expense.

- In bad weather it is harder to ensure that the fish achieve the desirable quality, and there is a high risk of accidents on board.

- The captain of one longliner told us that they hadn’t caught any fish in spite of trying with various kinds of dead bait. (The use of live bait is prohibited in Norway. It is widely used in commercial angling for bluefin tuna in other countries.)

- Dedicated, new sales channels and complex logistics make it difficult to achieve prices that reflect the resources invested.

Want better storage methods

The bluefin tuna fishery is a seasonal fishery where one big catch can push down both prices and quality.

Researcher Manu Sistiaga believes that freezing would make it possible to supply the market more gradually.

“If the fish is frozen to a temperature of -60 degrees Celsius, it can retain its quality for ten years. At -40 degrees it retains it for one month. But the containers capable of maintaining a temperature of -60 degrees use Freon gas, which is prohibited in Norway. Can we come up with any alternatives?” he asks.

Hope discussions will lead to research

Live storage is another option that researchers are interested in. It can maintain top quality over an extended period.

“We would anyway like to meet the fishers and the Directorate of Fisheries in order to get a better understanding of various challenges before moving onto specific projects”, says Sistiaga.