This article was produced and financed by Institute of Marine Research

Scientists found plastics in a whale back in 1971

A recently discovered report reveals that marine scientists found plastic in the stomach of a whale off Canada almost half a century ago. It pre-dates the famous stranding of a whale on the Norwegian island of Sotra in 2017 by 46 years.

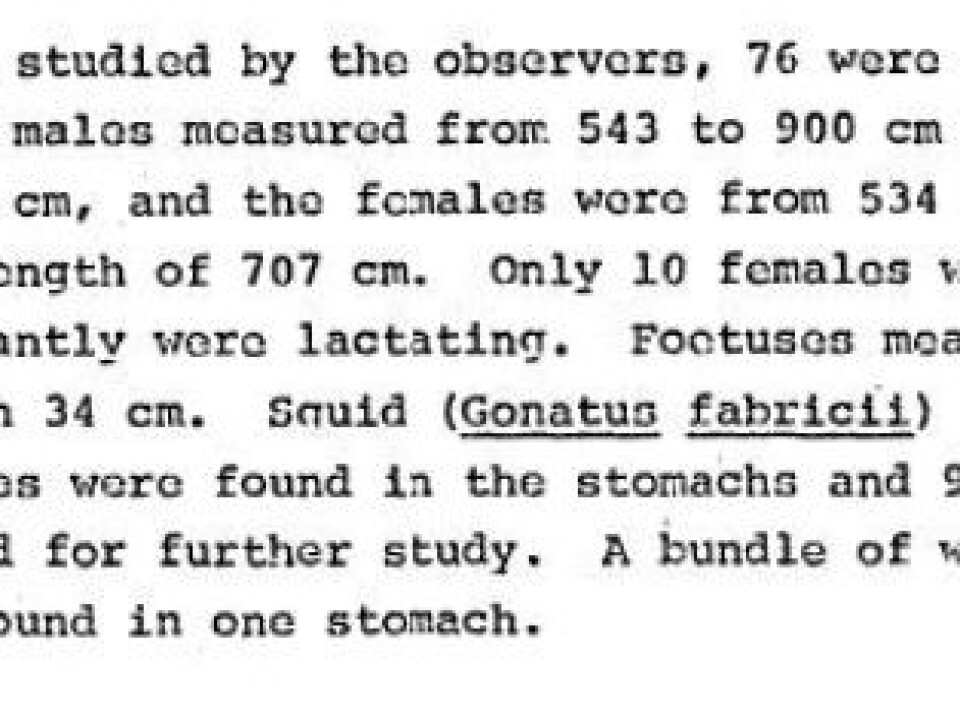

In conjunction with another project this summer, Åsmund Bjordal, a senior director at the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR), came across a document produced by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in 1971. The report, which describes an IMR whale survey off the coast of Labrador in Canada, contains one sentence of particular interest:

“A bundle of waste sheet plastic was found in one stomach.”

So scientists had found plastic in the stomach of a bottlenose whale 46 years before the more famous “plastic whale” stranded on Sotra Island in Norway, last year.

Discovery surprised experts

Bjørn Einar Grøsvik, a researcher at the IMR and expert in marine plastic pollution, was surprised when he heared about the report.

“It’s the first time I’ve heard of plastic being found in a whale so long ago”, he says.

In the 1960s and 70s far less plastic was produced than today, according to the IMR scientist.

“On the other hand, no plastic was recycled, and they were less aware that you shouldn’t throw things into the sea. So a higher proportion of the plastic that was produced in those days was probably thrown into the sea”, says Grøsvik.

Plastic smells like food

Plastic in the oceans cause several problems: First, animals like whales eat it and in doing so destroy their digestive system. That’s what had happened to the whale that stranded on Sotra. It died after eating more than thirty plastic bags.

“Animals mistake plastic for their natural food because plastic left in the water becomes overgrown with a thin layer of bacteria or algae which may emit a smell that animals misinterpret. They think it smells food”, says Grøsvik.

He explains that scientists know of around 700 marine species that are vulnerable to large pieces of plastic.

“These animals can also get caught up in plastic or in fishing gear that has been lost – what we call ghost nets”, says Grøsvik.

Plastic changes animal behaviour

The plastic in the oceans doesn’t disappear, but it is gradually broken down into tiny pieces that are impossible to see with the naked eye. These are known as microplastics, and they can also harm marine life.

“We know too little about the smallest particles, but laboratory experiments on fish using high concentrations of nano- and microplastics have shown that these particles can be absorbed by organisms and affect their behaviour”, says Grøsvik.

Experiments have also shown that microplastics can affect metabolism and cause inflammatory reactions.

The “plastic whale” that acted as a wake-up call

In January 2017, a Cuvier’s beaked whale stranded on the island of Sotra, west off Bergen in Norway. It had become ill after eating more than thirty plastic bags and was ultiamtely put down. The story of the whale moved and engaged people both in Norway and abroad, and helped to raise awareness of the dangers of marine plastics.

“The whale on Sotra played an absolutely key role in moving the problem of plastic up the agenda in Norway. The photos of it acted as a wake-up call to the general public, who responded by organising major beach clean-ups, for example”, says Grøsvik.

“Within a month of the Cuvier’s beaked whale stranding, various volunteer events had collected more than 100 tonnes of plastic just on Sotra”, he says.

New field of research

Back in 1971, researchers probably didn’t realise how big a problem plastic pollution would become, says Grøsvik. The plastic found was only mentioned in a single sentence in the ICES report, which was written by former IMR researcher Ivar Christensen.

“But it was great that they recorded what they found in the whale’s stomach”, says Grøsvik.

A quick search for the words “plastic” and “debris” in an online archive of scientific papers reveals that nothing was written on this topic before 1980. From 2012 onwards there was a sharp increase in the number of papers. If we add the search term “marine”, there was virtually nothing until 2000. Once again there is a marked increase over the past six years.

“So the plastic found in 1971 was an early observation. And it is important for us to know when something was observed for the first time”, says Grøsvik.