THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

An event is nothing without the media

100 years ago, the whole world followed the polar explorers' expeditions in the newspapers. Today we follow election results, the spread of viruses, and the development of war in real time.

After two years of pandemic, the summer of 2022 proved that there are many things that bring us together. In Norway, audiences found their way to festivals from Riddu Riđđu in the north to the Tree Boat Festival in the south, and 100,000 people gathered to watch the rap group Karpe in Oslo Spektrum arena.

In the news feeds, images of happy concertgoers were mixed with images from the war in Ukraine and updates about a stray walrus.

For Espen Ytreberg, a professor of media studies at the University of Oslo, it is clear what the funny and the more serious events have in common.

“The media is fundamentally important for large-scale events. That is the way it is today and that is how it has been way back in history,” he says.

In his new book ‘Media and Events in History’, Ytreberg describes how the structure and understanding of major events are inextricably linked to the way the media have evolved.

Regardless of whether it is the telegraph of the past and printed newspapers, or today’s social and digital media, it is through them that an occurrence becomes an event.

From monthly updates to ‘right now’

Today, we are able to follow sports championships and elections, but also unforeseen events such as a natural disaster or a pandemic, in real time. The constant updates are part of new media technology and influence how we experience what is happening.

“Today, simultaneity is extreme. ‘Real time’ is an ideology of absolute updating,” Ytreberg says.

Besides the fact that it is not really possible, the professor believes simultaneity has a downside.

“It is blown up out of proportion because there is too much going on ‘right now’. You can quickly become impatient and frustrated – it feels like you are falling behind if you don’t update all the time. And even if you do, the pandemic or the election still feels uncertain and unpredictable," he says.

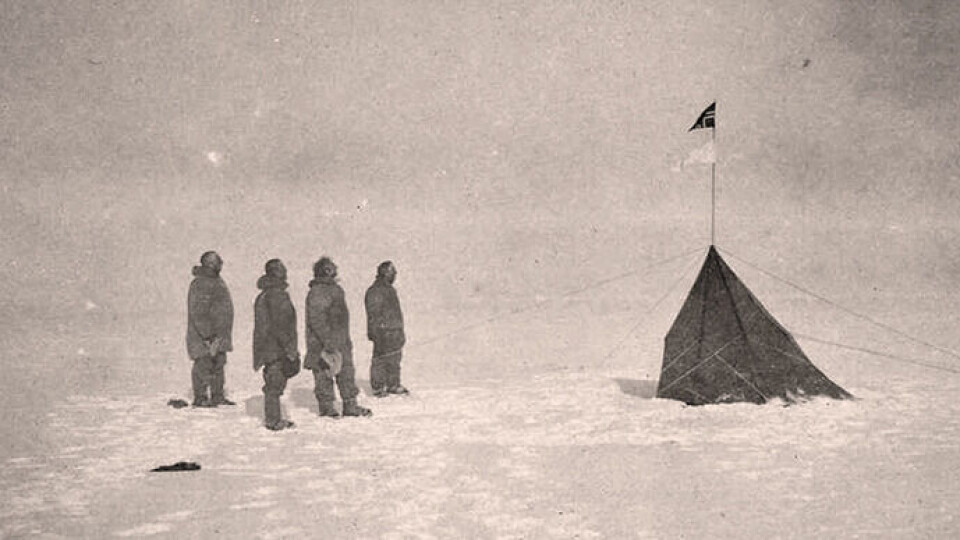

Ytreberg goes back in time and looks at how the influence of media technology has evolved historically. 111 years ago, when Roald Amundsen embarked on his expedition to the South Pole, everyone was following his progress.

“The flow of information was slow. Months could pass between each bit of news,” he says.

Nevertheless, the regular newspaper reports gave a sense of simultaneity.

“In June, one could read that ‘Amundsen has now received funding’. Later that month it was stated ‘he is starting his journey’, and in November ‘he has now arrived on the South Pole continent’. ‘Which route will he choose?’, was printed in March of the following year," he says. “The public knows that while reading this in the newspaper at home in Norway, Amundsen is struggling through the snow. And everyone is wondering about what will happen next.”

According to Ytreberg, this gives a mediated sense of simultaneity – the experience is conveyed through the media.

Pics or it didn’t happen

Amundsen himself was fully aware of how important the media was for the success of his expedition.

“He was obsessed with communicating his conquests, explicitly writing that ‘The fact was that what we had done would have no real value until it was brought to the knowledge of mankind’. Therefore, the race with Scott was not only to the South Pole, but just as much back to the telegraph," he says.

The philosophical question about the tree falling in the forest without anyone hearing it is reminiscent of the quality of an event. If you reach a pole and no one sees it, is it an event?

“For those at the forefront of events, mediation is rarely secondary. Politicians, for example, are very much aware that if they make a decision behind closed doors, the reality of it lies just as much in the communication," Ytreberg says.

Events bring society together

When Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole, Norway had been an independent nation for six years. The country needed something that would unite the people.

“Much of what was happening in Norway at that time can be explained by Norwegians’ need for acceptance that we have a place in the world as a nation. The nationalistic project was important to Amundsen, and even more important to those who financed him,” says Ytreberg.

Whether it be a pandemic, a polar expedition, the Eurovision Song Contest or an election, the events we care about play an important role in society.

“We are united by and live in the events. Whether it is a planned celebration or a sudden crisis, there is an outside and an inside, and there is a sense of community among those who participate," he says.

This is also the key to why he, as a media scholar, is researching the topic.

“Large-scale events make complex, modern societies possible. Therefore, the research is about looking at what binds us together, on which terms we are bound together – and who controls the instruments that make it possible," he says.

‘Eventification’ – the amount of events has exploded

In his book, Ytreberg goes back to industrialisation in the 1800s to look at how events come about. This is also the time when media becomes an industry.

“The media industry reproduces and creates several types of media. It does the same with events, which can now be produced in series. Therefore, this is goodbye to the notion that events occur organically – it is clear that they are created," he says.

In the 1800s, several Western societies became more democratic, and rulers could no longer expect people to participate in their events under duress.

“A softer power gained importance,” says Ytreberg.

Participation is achieved to a greater extent by capturing attention and creating excitement.

“The more you can map and channel people’s participation, transform them from passive spectators to active participants, the more power you have. This applies to the media industry, to Zuckerberg, to politicians and to anyone who wants to influence. This soft power is real — it isn’t necessarily gentler," he says.

This has intensified since democratisation during industrialisation, and two things have drastically changed in the way events capture our attention: The amount and the pace.

“There are many media technologies, and new roles and professions have emerged around events, not least communicators and PR people. Today, events are orchestrated on multiple platforms," Ytreberg says.

The media scholar devotes a chapter of his book to media-planned events, where the media themselves are in the driving seat when the events are planned, such as with large advertising campaigns or the Eurovision Song Contest. He also explains that many theorists have been critical of media’s active role.

“Although one may well find something vacuous in large orchestrated events, it is usually not the case that one can distinguish between events that are artificial and created by the media on the one hand, and ‘real’ events where the media is not important on the other. The media is more fundamental," he says.

Development in media changes events

A key point in Ytreberg’s book is that it is not possible to distinguish a large-scale event from its mediation. With a trend towards more and more media platforms, this is becoming more advanced.

“Both the physical and the mediated side of an event develops rapidly, and in interaction. But it is not the case that media development means that everything takes place in the media," Ytreberg says.

At a large festival, the essence is the large physical gathering of people. It is documented and reinforced simultaneously through news media and not least social media – the participants show that they were present on Instagram and Snapchat, while the newspaper publishes descriptions of the atmosphere and reviews. In addition, the festival lives in the media both before it physically takes place, and afterwards.

There are examples of events that do not take place physically – such as e-sports championships, or digital launches of new technology. But is it possible to call something an event if it doesn’t take place in the media? Ytreberg believes the answer is no.

“There are many historical examples of large crowds of people gathering and important things happening there and then – but they need to find out about it in some way or another. So, in one form or another, the media must always be involved in important large-scale events," he says.

The pandemic was a unifying event

The development of the media landscape has meant that everyone is no longer paying attention to the same things. While some people are interested in the Olympics, others are waiting for the Eurovision Song Contest or the next election campaign.

Planning major events has become more complex and requires expertise on multiple platforms. This does not mean that it is impossible, Ytreberg believes.

“Despite the fact that not everyone watches public broadcasting anymore, it does not mean that the era of major events is over. And we need them, so that large-scale societies can exist,” he says.

The media scholar also points to the COVID-19 pandemic as proof that it is still possible to attract everyone’s attention.

“It revived the sense of an event being a common experience, in the sense that it affected everyone, albeit not in the same way. There is no doubt that the media will continue to create arenas where catastrophic events are discussed and given meaning, whether it be a storm or a new virus," Ytreberg concludes.

Reference:

Espen Ytreberg: Media and Events in History, Polity Press, 2022. Overview.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

"Fascism must be countered with knowledge"

-

Asian leaders on social media: Share stories about their love lives, offer advice on radio shows, and play with cats

-

Demonstrations: Meeting face to face may be more important than ever

-

"Everyone knows it, everyone’s seen it. Most people have a perception of nightlife chaos”

-

Music in film and TV: “It's a form of manipulation”

-

Can you take antidepressants while pregnant?