THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Runes were just as advanced a written language as the Roman alphabet

In the Middle Ages, the Roman alphabet and runes lived side by side. A new doctoral thesis challenges the notion that runes represent more of an oral and less of a learned form of written language.

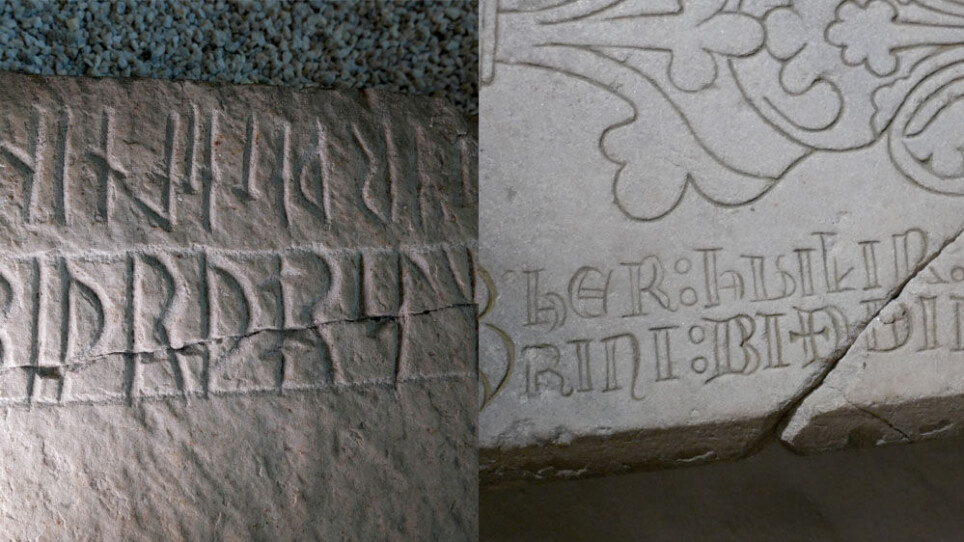

"Here rests Bishop Peter might have been inscribed on a gravestone from the 1200s. Some inscriptions might have been made using runes, others with Roman letters,” Johan Bollaert says.

He is a senior lecturer at the Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies at the University of Oslo.

He has investigated written language used in public inscriptions in Norway from the 1100s to the 1500s. Last autumn, he defended his doctoral thesis Visuality and Literacy in the Medieval Epigraphy of Norway.

Believes runes are no more oral than other inscriptions

The assumption that runes represent a more oral tradition is based on the idea that runic inscriptions are contextually bound and are rarely in Latin – which is associated with a scholarly culture.

“But Old Norse can also be written, and it is not written any worse just because it is the vernacular,” Bollaert says.

Another reason for the assumption may be that researchers have compared runic inscriptions with medieval Latin manuscripts.

“I think this is wrong, because inscriptions and manuscripts have different forms and functions. A manuscript is often written so that it can be read and understood out of context, i.e., in other places and times. A gravestone, on the other hand, was made to be placed and understood locally,” he explains. “While it is easy to write a sentence or two on parchment, it takes time and effort to carve words into a piece of stone. Therefore, the text used in inscriptions will be shorter and simpler out of necessity.”

Visual resources when using both runes and letters

What Bollaert has investigated is called epigraphy, the study of reading and interpreting inscriptions. He has compared letter inscriptions with runic inscriptions in wood, stone and metal. This is the first time research has been conducted on inscriptions of letters from the Middle Ages in all of Norway.

Since the use of written language in the Middle Ages largely took place in an ecclesiastical context, most of the texts are from gravestones and are stored in museums around Norway. The largest exhibition is located in a cellar at Nidaros Cathedral, while a few can still be found in cemeteries. He has also looked at graffiti on church walls.

Bollaert has analysed how points, spaces, figures and images are used, what he calls the visual resources of writing. His argument is that the more the visual resources are used, the more advanced the inscription is in its written form.

“The biggest difference between oral and written language is that oral language can only be heard, while the written can only be seen. That is why the visual aspects are so important in written language. An inscription that has detailed punctuation, a carefully planned layout and ornamentation shows better use of the writing’s visual possibilities than a text without punctuation and spaces,” he explains.

Here, he has found that the visual resources are used to the same extent on runic inscriptions as on those involving letters. However, there are some differences.

Letter inscriptions are more standardised

Runes are the oldest known form of writing in Norway and were in continuous use from the 200s to the late Middle Ages and into the 1400s. The Roman alphabet was introduced in Norway at the same time as the introduction of Christianity, gradually taking over from the runes.

An important difference between the findings of letter and runic inscriptions is that the letter inscriptions are associated with cities and episcopal seats, such as Nidaros, Oslo, Bergen and Hamar, while the findings of runic inscriptions have also been made in smaller places around the country. Most letter inscriptions have been found in Trondheim.

“The letter inscriptions are more standardised and similar to each other, for example they begin with a cross and Here rests. The explanation may be that they were produced in workshops affiliated with the dioceses. The runes were made locally and there is a lot of variation,” he says.

Dots indicated spaces

Another difference is the material that was used. Softer and lighter coloured types of stone were used for letter inscriptions, such as marble and limestone. Runes, on the other hand, are also found carved into hard types of rock such as granite and quartzite.

“In Nidaros, they primarily used marble that came from a quarry approximately 70 km north of the city. The stones used for the runes were local, they took what they could find in the local community. However, this does not mean that the runes represented less knowledge, or that they were executed more sloppily,” Bollaert says.

In inscriptions, it is common to place dots between the characters instead of spaces. In letter inscriptions, two dots were most often used, while several dots could be common in the runic inscriptions. The more important a word was, like a name of a deceased person, the more dots there were after the word to denote the spaces.

The enigmatic history of runes

The oldest runic alphabet consisted of 24 characters, and each character represented a sound. There is a clear similarity with classical alphabets, and it is therefore assumed that those who created the runic alphabet knew about other alphabets – such as the Roman one, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia.

But who mastered runic writing, and how was it taught?

Bollaert says that not much knowledge exists here; the runes have an enigmatic history.

However, he has made an interesting discovery indicating that it was expected that a good proportion of the population could read runes.

There are two reasons for this:

- He has found runic writing inscribed at church entrances through which most people would move.

- Letter inscriptions on gravestones often have a large image of the deceased, while runic inscriptions do not.

“The lack of drawings in the runic inscriptions shows that a high degree of literacy is expected, while the drawings found in the letter inscriptions may indicate that they were adapted to illiterate people,” Bollaert says.

What was the tradition of gravestones?

Gravestones with runic inscriptions are a tradition that dates back to proto-Nordic times, long before the Viking Age.

“Before Christianity was introduced, the stones were placed where people could see them, such as along a road, and not on the burial mound. Common men and women didn’t have gravestones erected in their memory, they were meant for the upper classes and other people who held high rank. Towards the end of the 1100s, it became more common to place gravestones in cemeteries,” Bollaert says.

In addition to ‘here rests’, there were often verses of prayers on the stones. Work and status were common, such as child, bishop, lord, or doctor. Family relations were also mentioned, such as ‘Anders’ wife’. The place someone lived was often mentioned as well, such as ‘Brynjólf of Ága’.

Bollaert says that Scandinavia differs from the rest of Europe in that no date was written on the stone. It wasn’t until the late Middle Ages that dates of death became more common in Scandinavia.

“We are now working on creating a database of both runic and letter inscriptions. It will be freely available online and I hope it will make the inscriptions more widely known,” he says.

Reference:

Johan Georges P. Bollaert. 'Visuality and Literacy in the Midieval Epigraphy of Norway', Public defence at the University of Oslo, 2022. Summary.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"