THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

Hidden conspiracies and love stories:

Researchers use AI to decode centuries-old encrypted letters

One of the letters revealed how the former Scottish queen Mary Stuart conspired against her cousin, Elizabeth I of England.

Encryption is crucial for data protection and cybersecurity today. It ensures that unauthorised individuals cannot access the stored or transmitted information. However, the practice of sending messages that can only be interpreted by their intended recipients is not new. It has been around for centuries, long before computers.

Since antiquity, people have used cipher systems to send secret messages.

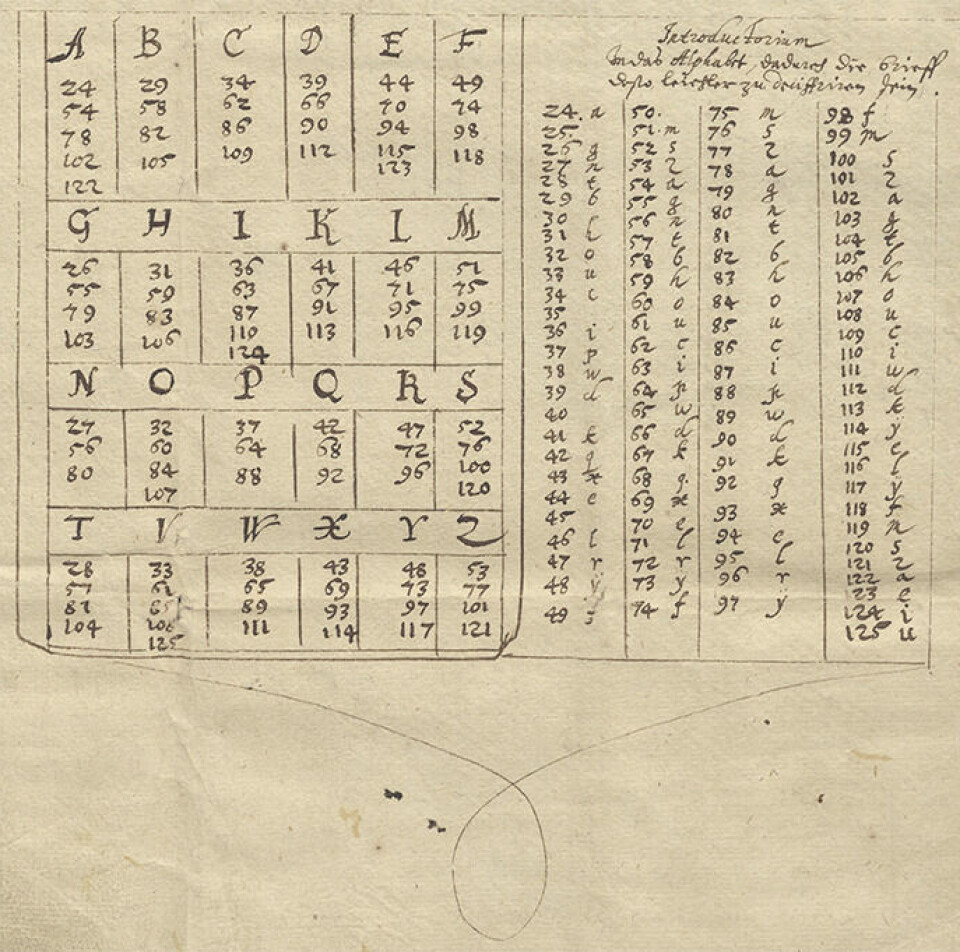

“A cipher system operates on a kind of formula described in a key. The key is shared only among the people who should be able to read it. One person encrypts, and the other decrypts using the key,” explains Michelle Waldispühl, a professor of German at the University of Oslo.

She is a professor of German at the University of Oslo.

In a cipher system, each letter might be replaced with a number. To make it harder to crack, the same letter can be substituted with several different numbers. This makes it harder to identify a pattern – unless you have the key.

Discovered conspiracy letters from Mary Stuart

Without the key, decoding a message is an enormous challenge. But Waldispühl and her research team found another way. Historians, linguists, and computer scientists joined forces to use artificial intelligence to uncover the secrets.

One researcher, George Lasry, made a significant discovery at the French National Library.

“He discovered over 50 letters in the same cipher system that turned out to be written in Mary Stuart's handwriting. No one had understood what they were, so they were archived in a very peculiar way,” Waldispühl explains.

The letters revealed how the former Scottish queen conspired against her cousin, Elizabeth I of England. She was imprisoned in the years leading up to her execution. However, she managed to send numerous encrypted letters from her cell to the French ambassador in England.

The Guardian described the decryption as the most significant new discovery about Mary Stuart in over a century.

Peace negotiations and love letters

Waldispühl and her colleagues have scoured old archives in search of cipher scripts to compile everything into a database.

“The material we now have in the database is primarily from the 18th and 19th centuries, and it mostly deals with diplomatic letters,” she says.

She has personally examined 15 letters sent to Axel Oxenstierna, the Chancellor of Sweden, from his ambassador in Germany during the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648).

“The letters contain reports from the war, details about peace talks, other ongoing negotiations, and the parties involved. They also contain a wealth of personal information,” she notes.

There is no consistent pattern for which parts are encrypted and which are written in plain text.

“When they were pressed for time, it's evident that not much was encrypted. Mainly, place names, personal names, and highly sensitive information were encoded,” says Waldispühl.

Not all encrypted messages revolve around war and peace. Love letters also needed secrecy.

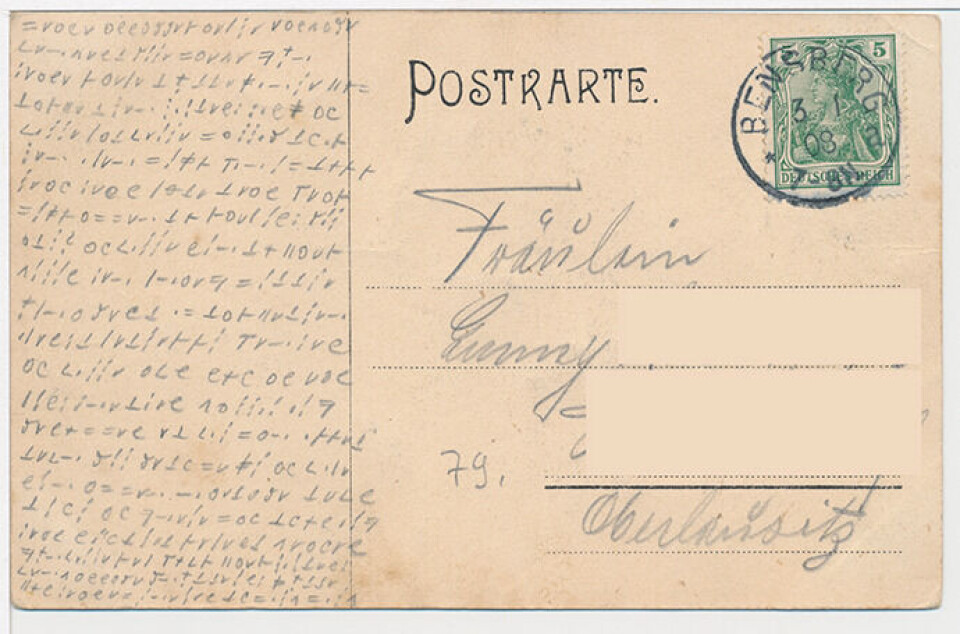

“From a private collector, we have received more than 400 postcards containing cipher script. They are from the late 1800s and early 1900s, and he found them at flea markets across Europe. Among them are love letters,” she says.

One postcard from 1908 begins with '=voevoeeoggvkov/l' and continues in the same incomprehensible way. Only the first couple of lines have been decoded so far. The text is in German and reads: 'Meine innig geliebte einzige herzensgute Miezefrau.' In English, this roughly translates to: 'My dearly beloved, only kind-hearted kitty.'

Deciphering cannot be left to machines alone

Throughout history, codes have evolved to become increasingly sophisticated. Each time a key is exposed, a stronger code is created.

By World War II, machines played a significant role in both making and breaking codes. One of the most famous coding devices from that time is the Nazi Enigma machine. Alan Turing and the British needed machines to crack the code.

Today, artificial intelligence and modern language models could help crack centuries-old ciphers. However, there is one major challenge:

“Conventional language models require vast amounts of material for training, which isn't feasible in this case. Sometimes we have as little as half a page of text to work with,” Waldispühl explains.

This is why the human element, known as the 'human-in-the-loop,' is essential. For instance, when a computer scientist encountered a letter where every part was encoded, the initial step was to transcribe the text. This involved translating the letter's characters into a format the machine could process. The transcription was then sent to the historical linguist at the University of Oslo for further analysis.

“I immediately saw that he missed a comma and a couple of dots over some of the characters. So, I corrected it with my philological eye,” says Waldispühl.

Then they used computer tools to match the code against texts in multiple languages. Despite these efforts, the researcher still could not fully understand the letter.

“So, I did a manual analysis to check what the machine might have gotten wrong. It's like a puzzle where we continuously update the key the machine is working with,” she explains.

The letter turned out to be campaign propaganda from the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. In the 1570s, he was trying to become king of Poland-Lithuania. The letter contained both promises of what those who supported him would receive and threats of military force against those who did not.

Developing tools for more unsolved mysteries

Waldispühl and her colleagues have compiled thousands of coded documents into their database, de-crypt.org. But their ambitions extend beyond just deciphering old, coded letters and postcards.

“We now aim to take a step further, not only by examining cipher scripts but also by expanding our focus to other writing and symbol systems, even those with limited data,” says Waldispühl.

This includes ancient scripts like the early Greek language Linear B and the 4,000-year-old Phaistos Disc from Crete, which remains undeciphered to this day.

However, the primary goal is to simplify everyday tasks when encountering a document of unknown content.

“The main aim is to develop models for transcribing and deciphering, and then to develop tools that can benefit everyone,” Waldispühl explains.

If her vision becomes reality, in a few years, you may be able to upload a picture from your phone and get a complete decryption in seconds.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family