THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

The end of witch trials did not stop religious persectuion of Norway's indigenous Sámi people

When it came to the Sámi people, a persistent fight continued against what was termed the art of witchcraft, and missionaries took over from the judicial system.

The 16th and 17th centuries were characterized by widespread witch hunts against people accused of witchcraft. In Norway, approximately 750 people were accused of witchcraft and around 300 of them sentenced to death, many of them burned at the stake, and many of them Sámi.

Researchers have been able to conduct an extensive examination of what happened in northern Norway, including who was accused, what they were convicted of and what the punishment was. They conducted their review by examining court records.

Of the 91 people sentenced to death in the northernmost part of Norway, Finnmark, 18 were of the indigenous Sámi people.

The South Sámi area

Many questions still remain about what actually happened in central Norway and in the South Sámi area, so historian Ellen Alm has tried to gather as much information as possible. Through court records, she found that three Sámi people were accused of witchcraft: Finn-Kristin, Anne Aslaksdatter and Henrik Meråker, the latter of whom received a death sentence.

Since many Sámi people had Norwegian-sounding names, there may have been more.

Finding new information

PhD Candidate and historian Anne-Sofie Schjøtner Skaar at NTNU is now in the process of studying cases of witchcraft and magic that took place at Inderøy, Namdalen and Stjør- and Verdalen District Court in the 18th century.

By thoroughly reading and studying the court records from Nord-Trøndelag County, she is discovering new and interesting information.

She is investigating how the prosecution of witchcraft was gradually abolished during the 18th century.

“Hardly any research has been conducted into how the prosecution and phenomenon of witchcraft cases came to an end, so it is interesting to investigate. I am also studying whether Sámi people in the South Sámi areas were still being prosecuted in the 18th century,” says Anne-Sofie Schjøtner Skaar.

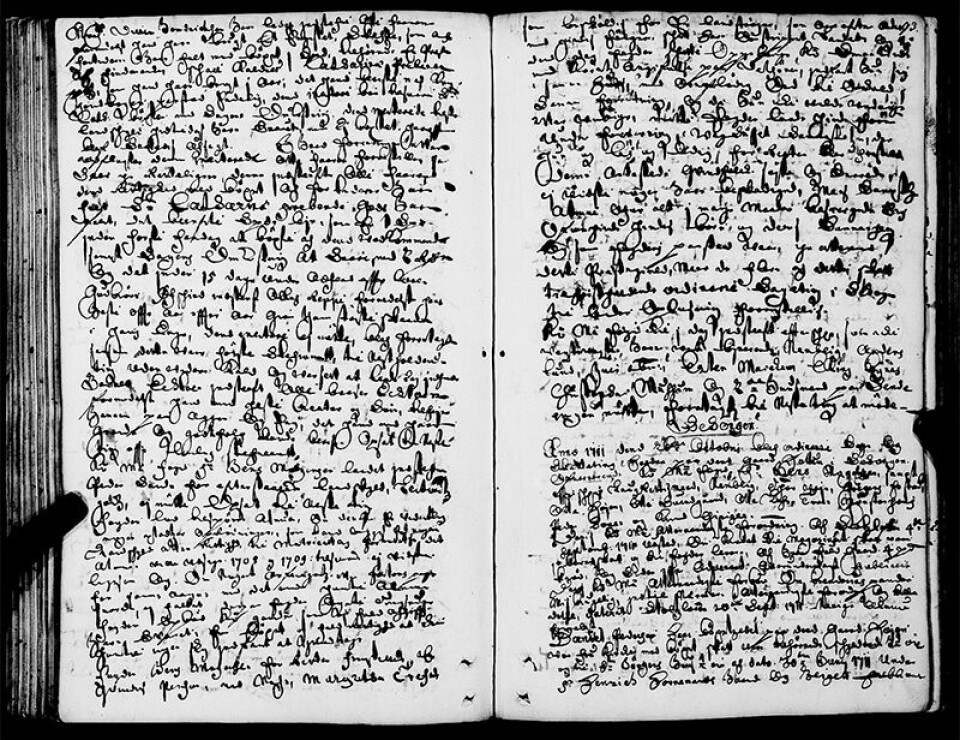

Written in Gothic script

So far, in her review of court records, she has not found Sámi people who were accused or convicted of witchcraft in the 18th century in Nord-Trøndelag, but she hasn’t yet gone through all the records. It is painstaking work; the records are written in Gothic script and each secretary also has their own distinctive way of writing.

“I learned Gothic script at the University of Oslo when I wrote my master’s thesis on witchcraft in Mora and Rendalen in the 17th century. I can now read Gothic script pretty well, but it takes time to go through all the documents,” she says.

In addition to court records, she is also studying accounts written by missionaries from the same period, something we will come back to later.

Witch trials slowly disappear

There are several reasons why the horrific prosecution of witchcraft was finally phased out during the 18th century.

During the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries, it was illegal to use torture to force confessions, and convicted criminals weren’t allowed to be witnesses either. This meant that in theory, a convicted ‘witch’ could not reveal the names of other ‘witches’.

“However, it was not uncommon to turn a blind eye to the law in witchcraft cases: torture was used, and convicted ‘witches’ were forced to name their accomplices. The letter of the law was interpreted and practiced very differently, which led to many witch trials during the period,” says Anne-Sofie Schjøtner Skaar and adds:

“In the late 17th century, the judicial practice begins to change. Several of the law speakers became stricter, required proper evidence and stopped accepting the use of torture. The law speakers also became better educated and professional, and they influenced and taught local district judges.”

Towards the end of the 17th century, more and more judges actually began to follow the law, which is when it became difficult to bring cases of witchcraft to court.

“How can an imaginary crime be proven if it is no longer acceptable to force someone into a confession?”

The practice of forced appeal was also introduced by Christian V’s Norwegian Code of 1687. This meant that strict penalties could be appealed to the appeals court so that the accused could have their case tried in a more professional court.

In the 18th century, Europe entered the Age of Enlightenment where science, reason, tolerance and progress gained a foothold, and this helped change perceptions and attitudes.

Horrible reading

However, when the prosecution of witchcraft disappeared, another mechanism took over to monitor and fight against the Sámi religion and how it was practiced: missionaries entered the scene.

“It seems that the missionaries took over from the judicial system in order to ‘deal with’ the Sámi religion and its practice,” says Schjøtner-Skaar.

There is good evidence of this in missionary accounts from the 18th century.

“Some of these missionary accounts make for horrible reading. We find descriptions of Sámi people engaged in the ‘sorcery of the devil’. The missionary accounts show that the Sámi religion was still being interpreted by some as witchcraft and the Devil’s work, even though the judicial system no longer seemed interested in prosecuting this anymore,” she says.

Priest Johan Randulf, author of the Nærøy Manuscript, writes that ‘the South Sámi have many different gods, but that they all belong to the Devil’.

“I know that he, along with all other [Sámi gods], is the Devil himself.” This is how the priest describes one of the South Sámi gods, and he also describes joik, the traditional Sámi style of singing, as the ‘song of Satan’.

The Sámi Apostle

Across much of the Nordic region and since the early Middle Ages, there were many attempts to Christianize the Sámi, but it was only after the establishment of the College of Missions in Copenhagen in 1714 that the missionary work really started.

One of the most zealous missionaries was Thomas von Westen (1643-1727) from Trondheim. He was nicknamed the Sámi Apostle. In 1716, Thomas von Westen was appointed to lead and organize the Sámi mission, and from then on, Trondheim established itself as a powerhouse for the Sámi mission through von Westen’s education of Sámi missionaries.

Witchcraft amnesty

Thomas von Westen was constantly concerned that Christian education for the Sámi people must take place in their own language – Sámi – and that conversion should be personal and heartfelt.

Thomas von Westen and other missionaries spoke to the Sámi and intensely questioned their beliefs and practices. The missionaries got a lot of information, but they noticed that not all Sámi people dared to talk about their beliefs and practices.

“This eventually led to von Westen introducing an amnesty for the Sámi so that they could not be prosecuted under the witchcraft law no matter what they told the missionaries. This was meant as a kind of insurance for the Sámi people so that they would dare to talk more openly with the missionaries,” says Schjøtner-Skaar.

However, the amnesty did not prevent the Sámi culture from being demonized.

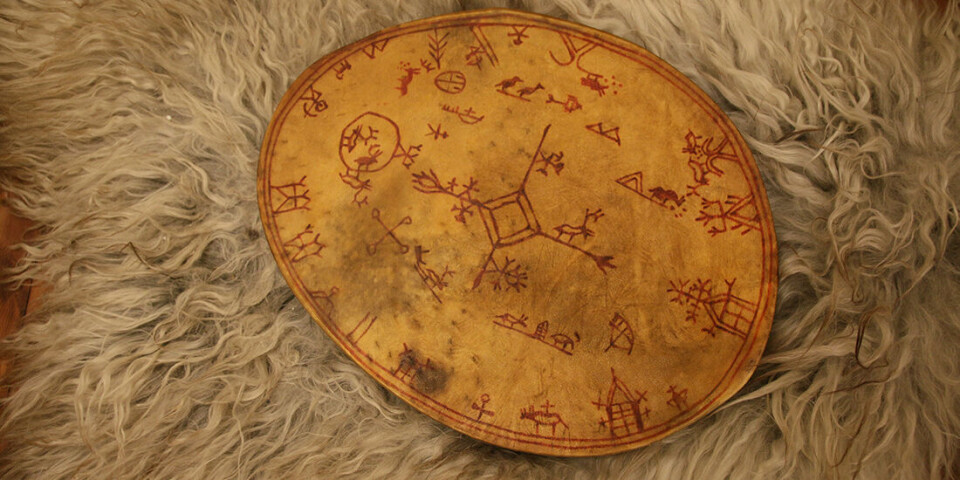

Confiscated ceremonial Sámi drums

Among the more brutal methods used by von Westen and the other missionaries throughout the missionary period were the confiscation of ceremonial Sámi drums and the destruction of sacrificial sites and sacred places in nature. The zealous missionary was responsible for the confiscation of over 100 ceremonial Sámi drums.

Most of the drums were sent to Copenhagen, and many of them were unfortunately destroyed in a large fire in 1728.

However, some of the drums confiscated by missionaries ended up in other museums or with private collectors. One of these was the Folldal drum, which von Westen confiscated in Namdalen.

This drum eventually ended up at Meiningen Museum in Germany. In 2023, it was finally returned to the South Sámi area and is currently on display at the Saemien Sijte Museum in Snåsa.

You can read about the Folldal drum and what the different symbols mean in this Wikipedia article.

The drink of the devil

Thomas von Westen was also a strong proponent of introducing a ban on alcohol.

“On 1 February 1723, the Norwegian missionary Thomas von Westen turned up at the local assembly in Overhalla. He believed that the Sámi consumption of alcohol stood in the way of their conversion to Christianity, and he ordered Norwegians to stop selling them spirits and beer. When the Sámi people imbibed ‘Zathan’s loche drich’, they soon began practising their pagan religion and witchcraft, according to von Westen,” Skaar wrote in this article: Lappernes og finnernis forførelse ved brendevin og øel (Historikeren No. 2 2023 – from page 26).

Thomas von Westen ended his speech by asking for the Sámi ‘pagan’ burial customs in the mountains to be banned, and that all Norwegians who had Sámi children in service in their homes must ensure that they received a Christian education and no Sámi should be without permanent work.

Margareta Mortensdatter Trefot

“As part of the research project, I am also interested in attitudes towards South Sámi religion, which Norwegians often labelled as witchcraft and idolatry,” Skaar said.

Witchcraft charges brought against Margareta Mortensdatter Trefot is one of the cases she wants to study more closely.

“I am somewhat uncertain about ethnicity here, as the accused is called a ‘finn’ by the local district judge, which along with ‘lapp’, was often used to refer to the Sámi. Margareta said she was originally from eastern Finland. This is a known case, but it has not been analysed before, so I am going to include an analysis of it in my thesis,” she says.

Margareta Mortensdatter Trefot was a beggar woman who, according to witnesses, walked around wishing people harm by casting spells on them if they would not give her money, food or accommodation.

The case was first heard at a local assembly in Verdalen and is mentioned in court records in the period 1711–1712.

“Margareta then accompanied the local district judge and the bailiff on their court visits and was presented at several district courts, where many people testify that she wished them harm,” says Schjøtner Skaar.

The source is court record No. 6 from Stjør and Verdal District Court, 1709-1715.

“She was then charged with engaging in evil witchcraft, but I don’t yet know how this case ended because I haven’t found anything more about the verdict from the sources,” says Anne-Sofie Schjøtner Skaar.

She is also studying to what extent and in what form magical practices and beliefs lived on throughout the century. We will find out more about this later on, as well as what happened to Margareta Mortensdatter Trefot.

References:

The Devil Loose in Rendalen – One of The Last Witchcraft Trials in Norway, in Heimen vol. 58 (No. 2).

En rettshistorisk komparasjon av trolldomsprosessene i More (1669) og Rendalen (1670–1674). Master’s thesis, 2019, University of Oslo

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

More content from NTNU:

-

Fish farming is least harmful to the seabed in the north

-

Study: Centralising hospitals has reduced birth mortality

-

Early testing of schoolchildren: “We found absolutely no effect”

-

This determines whether your income level rises or falls

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable