THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY Fridtjof Nansen Institute - READ MORE

100 years have passed since Fridtjof Nansen received the Nobel Peace Prize. Would he have been given it today?

Nansen devoted much of his life to work for prisoners of war, refugees and victims of famine.

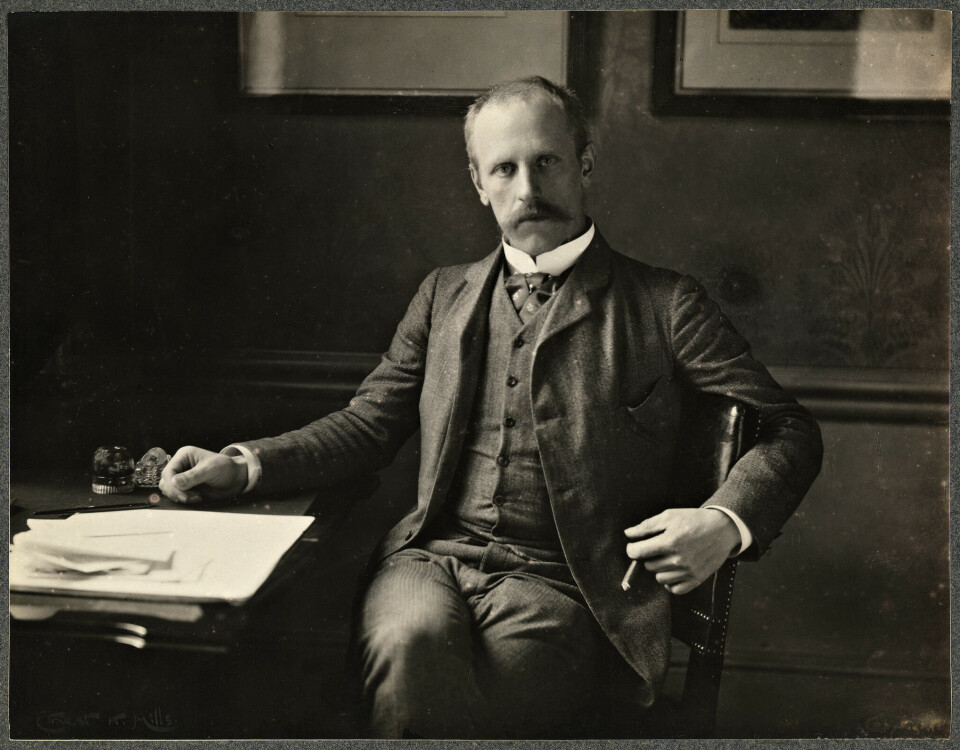

Fridtjof Nansen is perhaps the world’s most famous Norwegian of all time. He was an Arctic explorer and discoverer, a scientist, nation-builder and diplomat. He devoted the final decade of his life to building up major international institutions for inter-state cooperation and humanitarian work.

Again and again, he was brought in by his government to deal with new problems facing Norway and later the international community.

It is now 100 years since the polymath Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In that connection, Iver B. Neumann, who has specialised in the study of diplomacy, turns the spotlight on the diplomat Nansen.

“Nansen was the most influential diplomat Norway has even produced,” Iver B. Neumann says.

He is director of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, and a researcher specialised in the history of diplomacy. Neumann argues that the original motivation for the Nobel Peace Prize is equally valid today as it was 100 years ago.

Diplomatic hero

Neumann notes how, in his capacity as diplomat, Nansen was involved in two important innovations: the establishment of the independent Kingdom of Norway; and what became known as the 'Nansen Passport', which gave refugees and stateless persons the right to move across national borders to safety.

Immediately after the turn of the century, Nansen was deeply involved in Norway and nation-building.

“Nansen was indeed clever in how he paved the way for what he deemed best for Norway," Neumann says.

Getting things done

“As a diplomat, Nansen took risks and went his own way. He was an impatient man, with scant respect for the bureaucratic procedures that had evolved over the years before he himself began to serve as royal emissary,” Neumann explains.

He sees Nansen as a figure who would have been at home in the world of diplomacy in 1700s and 1800s – an aristocrat with plenty of elbowroom.

The government selected Nansen as an emissary, with responsibility for negotiating and entering into agreements on behalf of Norway. However, by the turn of the century, diplomacy was increasingly becoming the extended arm of the state, involving assignments for the nation. But not Fridtjof Nansen – he was, and remained, his own master.

Diplomacy as we know it today was still in its infancy, and not a field in its own right in Norway.

"Norway’s emissaries at that time were generally not professional diplomats. Quite the contrary, they were often professors in various other disciplines, ranging from law to biology . And Nansen himself was only a part-time diplomat," Neumann says.

At that time, Nansen was an old-fashioned diplomat. The world had changed, but he remained in a centuries-old world of aristocracy. All the same, he succeeded in many of his initiatives – so the age of heroes wasn’t over, at least not in the world of diplomacy.

Nation-building

For Norway, the years around the turn of the century were characterised by nation-building and efforts to ensure support for Norway as a new, independent nation.

“When Norway left the union with Sweden in 1905, it was essential to consider how best to ensure that Norway remained independent. Nansen himself favoured a republic, but recognised the wisdom of establishing a monarchy. He travelled personally to Denmark to speak with the Danish Prince Carl and his wife, Princess Maud, in the hope that they would accept the offer to become Norway’s king and queen. Which they did,” Neumann says.

Maud was the daughter of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra of Great Britain. Nansen and his allies recognised the importance of having close links to Britain – the world’s mightiest power at the time

It was essential to ensure British support to Norway’s secession from the union with Sweden, with lasting guarantees of security-political protection from Great Britain.

As noted, Nansen had a background from the aristocracy, and was a much-celebrated explorer and adventurer. All this provided him with a wide-ranging network to draw on when he was sent as emissary for the prime minister of newly-independent Norway .

Looking to the outside world

When Norway broke loose from the union with Sweden, almost all Norwegian diplomats resigned.

Nansen became the first Norwegian emissary to Great Britain, and London is among Norway’s oldest overseas stations. When he was posted to London in 1905, his focus was on Norway and Norwegian interests.

Gradually, however, as he became better acquainted with the wider global order, he became a firmly committed idealist, in line with Woodrow Wilson.

Nansen became increasingly concerned with establishing systems to ensure international cooperation in order to ensure peace and interaction across national borders.

Having been involved in ensuring peace and independence for Norway, he turned increasingly to the realm of international politics and humanitarian work.

One-man diplomat

“After WWI, there were many who had lost faith in diplomacy and diplomats – and Nansen was among those sceptics. Diplomats were seen accomplices responsible for the outbreak of the war,” Neumann says.

Nansen was involved in establishing the forerunner to the United Nations – the League of Nations. And here he was adamant that the League of Nations should be headed by representatives of the people – not professional diplomats and bureaucrats

“Nansen spurned diplomacy as an institution. He himself was notoriously difficult to work with. It’s actually quite a paradox that he became so engaged in international cooperation when he himself was such a headstrong loner,” he says.

Revolutionary ideas in international law

“Nansen managed to achieve an incredible amount in the 1920s. That was a decade of considerable international tension, but he doesn’t seem to have let himself be affected by all this," Cecilie Hellestveit says.

She works at the Norwegian Academy of International Law.

"Against the odds, he managed to achieve amazing results in the field of what was to become International Relations. He appears to have been endowed with self-confidence and horizons that lawyers and diplomats enabled him to break free of the frameworks that constrained lawyers and diplomats,” she says.

In 1922, the Nansen Passport, issued by the League of Nations, was established. This document gave rights to persons who had fled from Russia or had had their citizenship revoked. It was rapidly accepted by 50 countries.

“The Nansen Passport was the first-ever internationally recognised document for the protection of refugees. Even more important: in 1928 he negotiated an expended form of protection, now to Armenian, Turkish and Assyrian refugees. For the first time, refugees were accorded individual rights in an agreement between states. It was a revolutionary idea - that individual had rights under international law. This was a key component in what was to become international refugee law,” Hellestveit explains.

In 1928, Nansen elegantly managed to ensure better legal protection of Syria’s Kurds than the world has done after 2011.

Why was Nansen awarded the Nobel Peace Prize?

Fridtjof Nansen is celebrated for his work for refugees. Indeed, it was for this involvement that he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

The historian Carl Emil Vogt, who has written his doctoral thesis on Nansen’s work for refugees, notes that, despite the flowery celebratory speeches and the accompanying myths, Fridtjof Nansen did in fact accomplish humanitarian work of the first class, well deserving of a Nobel Prize.

In 1920, Nansen was asked to serve as the first High Commissioner of the League of Nations, a post he retained until 1927.

“The world had entered a period when the one catastrophic refugee crisis followed hot on the heels of the previous one,” Neumann explains.

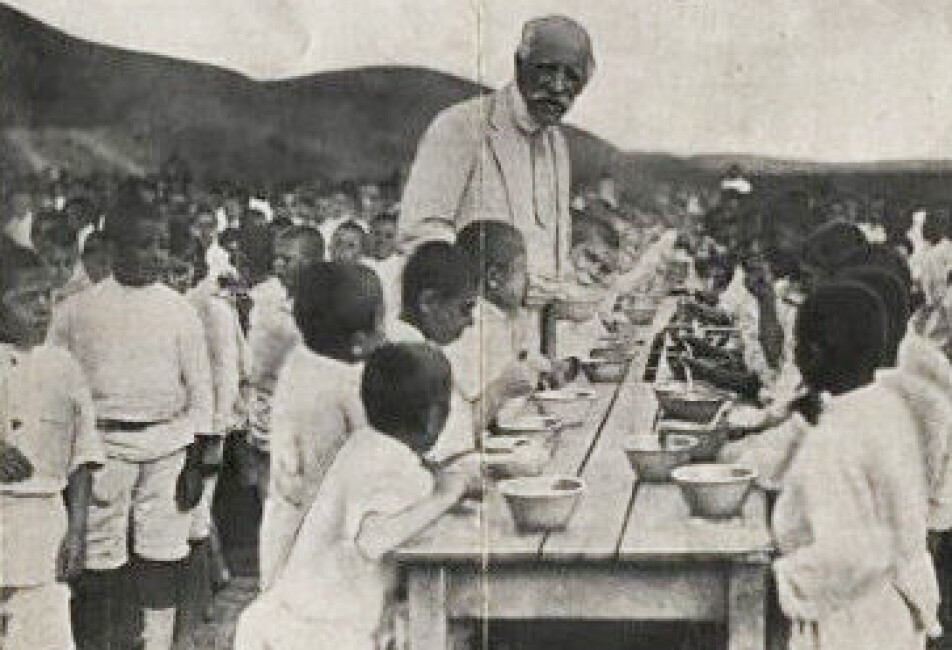

In 1920, Nansen had directed massive efforts aimed at easing the disastrous famine in Soviet Russia. Next came extensive work on getting a system established for the exchange of WWI prisoners of war (POWs). Two years after the peace accords had been signed, many POWs had still not been set free.

“Nansen helped to ensure that several hundred thousand refugees could return to their homes,” Neumann notes.

As if this were not enough, Turkey began its gruesome genocide of the one million Armenians who had been living on Turkish territory, and then proceeded to attack Greece because the Turks were dissatisfied with how the Treaty of Paris had split up the previous Ottoman Empire.

"Even now, Armenians come to lay wreaths on Nansen’s grave here at Polhøgda. Many of them have explained: I wouldn’t be living today, if it hadn’t been for Nansen,” he says.

Reference:

Iver Neumann. Diplomaten som helt: Fridtjof Nansen (link in Norwegian) (The diplomat as hero: Fridtjof Nansen), Internasjonal Politikk, 2022.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

This article/press release is paid for and presented by Fridtjof Nansen Institute

This content is created by Fridtjof Nansen Institute's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Fridtjof Nansen Institute is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more.

See more content from Fridtjof Nansen Institute:

-

“It's been a long time since we've seen so many positive developments in such a short period. We may indeed be entering a turning point for nature”

-

Russia could lose its big chance in the global gas market

-

Russia pushes for a fossil economy. Can China stop them?

-

What does China aim to gain in the Arctic?

-

Where do the metals in your electric car come from?

-

Power struggle in the Arctic Council: Greenland demands a leading role