An article from University of Oslo

Norwegian law protects those who pollute the Russian coast

Norway does not take responsibility for oil spills that are transported with the ocean currents and hit the northern coast of Russia. Ecosystems may be destroyed as a result.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The Barents Sea is one of the last clean, rich and highly productive marine ecosystems in the world. It is teeming with life: huge stocks of cod, herring and capelin, sea mammals and some of the world’s largest colonies of seabirds.

This large, biological production is the result of a fortunate combination of favourable ocean currents and shallow waters; the Barents Sea has an average depth of 230 metres. The most food and the greatest productivity are found at the polar front, where warm water from the Atlantic Ocean meets cold water from the Arctic Ocean. But the ecosystems are vulnerable. In fact, there is less biological diversity here than farther south, and the food chains are shorter.

Critics have pointed out how catastrophic the results of an oil spill in the Barents Sea can be, especially near the sea ice cap in the Arctic.

“Fortunately, the compensation rules are rather strict. The polluter must pay. The marine life must be safeguarded. But the law’s good intentions have their geographic limitations,” says Professor Erik Røsæg of the Scandinavian Institute of Maritime Law at the University of Oslo. “The philosophy is clearly to safeguard Norwegian, not foreign, interests.”

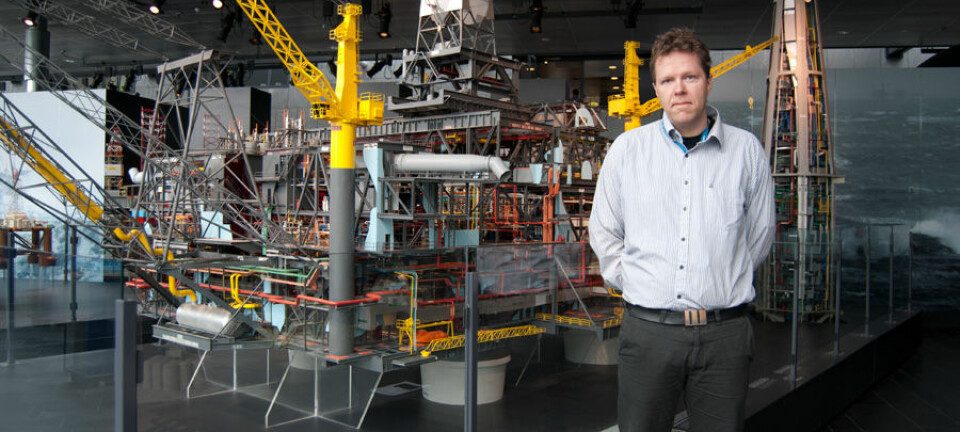

Røsæg is referring to the Norwegian Petroleum Act, which regulates how the authorities manage Norwegian oil and gas resources on the Norwegian continental shelf. An entire chapter is dedicated to rules for compensation when an accident has occurred – when oil gushes uncontrollably from platforms and other installations in the Norwegian sector.

“According to legislation, it doesn’t matter whether the oil company responsible for an oil spill is Norwegian, Swedish, American or Mexican, for that matter. What matters is where the damage occurs,” says Røsæg to the research magazin, Apollon.

Røsæg has thoroughly analysed the Norwegian rules on liability and the legal issues related to compensation that may arise.

“It’s important to understand the consequences of what the law says. What if the oil spill flows into other areas? What if the oil simply does not respect the Norwegian-Russian border?”

He asks us to imagine that an oil spill has occurred from an oil platform in one of the Norwegian fields located very close to the Russian border, that is, along the new demarcation line.

“The case is clear-cut for any injured parties who are Norwegian: Hotels and cabin owners whose beaches are spoiled, fishermen whose nets are ruined, and others can sue the licensees. The licensees are those who have been awarded the concession to extract oil, for example, whether they are Norwegian or foreign oil companies,” explains Røsæg.

The compensation rules are strict – much stricter than in many other countries.

“The injured party will receive compensation on objective grounds, without fault and without limitation, as the law stipulates. This means that it is not necessary to show an error has been made. And whereas an oil tanker that leaks oil is liable only up to a certain amount, there is no ceiling on liability for pollution from oil activity.”

Does not apply to Russians

But what if the oil flows eastward and hits the vulnerable coastal environment on the Russian side?

“If I were Russian, I would get a rather different response: ‘Sorry, but the Norwegian Act applies mainly to damage that has occurred on the Norwegian continental shelf. The damage you want compensation for, however, lies outside of our area of responsibility. Therefore, you cannot demand compensation under Norwegian law.’ The Act also explicitly states that the licensee can only be held responsible for pollution-induced damage under the provision of this law.”

It was when Røsæg was working on a chapter in his book Offshore Contracts and Liabilities, which was published last year that he gained a full understanding of Russia’s unfavourable position.

“I was quite surprised,” he says to Apollon.

“How do you interpret this?”

“I look at it like this: Although Norwegian authorities have taken the initiative on oil activity in the north and have recognised the need for strict compensation rules, they have chosen not to safeguard Russian interests.”

Does not recognise a court judgment

Røsæg notes that if he were Russian, he could of course approach a Russian court and sue the polluter via that route.

“This is very usual, and it happens in Norway too: When a foreign ship pollutes our coast, we sue that ship in Norway.”

But according to Røsæg, the problem does not stop there.

“There is every reason to believe that you, as a Russian, would get a judgment in your favour in a Russian court,” he asserts. “The Russian compensation rules are extensive, and they will often award a greater amount of compensation than the corresponding Norwegian rules.”

“But if the licensee on the Norwegian side does not recognise the judgment, and thus refuses to pay the compensation, a problem arises. In fact, there is no way to force the polluter to pay. We have no agreement with Russia, like we have with most other European countries, on mutual recognition and execution of court judgments.”

“Why doesn’t Norwegian law safeguard Russian interests in a better way?”

“First of all, I think the Norwegian authorities have thought that the most important thing, after all, is to look after our own interests. Secondly, the intention has probably been to try to push through bilateral treaties, meaning agreements between two parties, in this case Norway and Russia. In fact, the law allows for this. Norway has several treaties with its neighbouring countries in the east on the pollution issue. But no treaty on compensation arising from an oil spill that crosses the demarcation line exists.”

Røsæg does not think it is by chance that the rules are so restrictive.

“On the contrary. The Norwegian legislator has consciously sought to limit the scope of the law. I see at least two clear indications of this: The law contains special provisions for damage to fishing equipment and the like outside the continental shelf. But the rules apply only to Norwegian fishing equipment. Here we see our fierce nationalism coming to the fore,” says Røsæg.

Røsæg finds another clear indication that the Norwegian compensation rules are not intended to apply to Russia in the Nordic Environmental Protection Convention from 1974 between Norway, Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

“The convention ensures equal rights for Nordic citizens, so that citizenship is not significant for the right to compensation. It would have been natural to interpret the convention on this point to mean that it applies to the continental shelf of the Nordic countries. But in Norway we don’t see it like that. No, in the Petroleum Act the legislators have chosen to interpret the Environmental Protection Convention in a restrictive manner, so that it only applies to the countries’ land mass and territorial waters, that is, up to 12 nautical miles from land. Outside, on the continental shelf, Danes and Swedes are treated like Russians.

There is nonetheless an important difference between our small Nordic brethren and our big brother to the east:

“As mentioned, the Nordic countries have signed treaties on mutual recognition and execution of court judgments. A judgment against a Norwegian licensee in these countries can be enforced in Norway. As an injured party with Russian citizenship, you will still find yourself at a disadvantage,” states the legal scholar.

Spoil things for ourselves

Erik Røsæg reminds us of something we might not think about, but that may be relevant in this context: A Norwegian court does not always use Norwegian law. For example, when taking a decision as to whether or not a marriage is valid, the outcome cannot depend on the country in which the legal proceedings are brought. When lawsuits regarding compensation for oil-spill damage come before a Norwegian court, it may be said that the case has a closer connection to Russia and that we therefore will apply Russian law.

“Such a provision was originally incorporated into the Act, but it was removed. This small loophole was closed again in the new Petroleum Act of 1996,” says the professor.

He thinks Norway’s restrictive attitude is extremely unfortunate – including for Norway. The ocean currents in the Barents Sea where oil extraction is planned flow eastward. It is therefore likely that a spill on the Norwegian side will end up on the Russian side. The vast, marine ecosystems in the Barents Sea straddle the demarcation line. One of these systems lies north of Norway and Russia.

“When an oil company on the Norwegian side does not pay for pollution-induced damage that affects the Russian part of the Barents Sea and the coastal environment there, the risk is high that it will not be cleaned up. In this case, we are also destroying our own ecosystem.”

Assessment of environmental damage

“How does the oil industry view this?”

“Compensation liability under Norwegian law is strict, and it is recognised by the industry. But Norwegian law only addresses the strictly economic damage of oil spills. The Russians, however, have added ecology to their calculations. If an oil spill results in the death of fish fry, yes, compensation must be paid. A large amount. The Russians have formulas for calculating this. This is why it is probably better for the oil companies to be sued in Norway than in Russia.”

Røsæg mentions another thing that means oil companies that have polluted the Russia coast might prefer to have the lawsuit heard in Norway. “The procedural rules in Norway make it attractive to bring a lawsuit in Norway. Here the rule is that all cases must be heard in a single court, and deadlines for bringing a case to court may be set. In addition, all responsibility from the licensees that operate an oil field and from those who have made an error is channelled to one individual operator. When all the claims are combined in this way, they are much easier to deal with.

Røsæg points out that it is also better to file a lawsuit and know what you are getting than to risk a potentially long, uncertain process in Russia. “I think the oil industry views this like I do, that they would be better served by expanding the Norwegian rules.”

“Must be adapted to the reality”

Apollon contacted the Norwegian Oil and Gas Association, a professional body and employers’ organisation for oil and supply companies on the Norwegian continental shelf.

“How does the oil industry view a possible expansion of the Norwegian rules?”

“The Norwegian Oil and Gas Association complies with the current legal compensation rules as they are laid down in the Petroleum Act, the Pollution Control Act and international conventions,” says Oluf Bjørndal, Manager of Legal Affairs, to Apollon.

“We are concerned that the framework at any given point in time is adapted to the reality we are living in,” he emphasises.

“Petroleum activity in the northern areas makes it natural to discuss this situation with the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.”

International

Can Norway afford to be so selective in terms of who it gives the legal right of compensation to? What does international law say about this?

According to Erik Røsæg, there are no clear, international rules on this.

“Most countries, and Norway above all others, build on the principle that polluters must pay. The line of thinking is this: It should not be free to pollute, because then there is even more pollution. The compensation rules in the Norwegian Petroleum Act contradict this principle,” he points out.

“Are there any rules in international law that make an entity liable for compensation?

“That would be a bit difficult, and the rules apply regardless of the state’s liability. If the state has allowed an activity that should not have been allowed, it may be held responsible. But it would be better to have effective, international rules regarding liability for those who carry out oil activity. The UN International Law Commission has prepared draft rules on this issue. In fact, the commission refers to the Nordic Environmental Protection Convention, and has said that companies must be on equal footing with the local populations. But this has not yet been recognised as an international principle,” says Røsæg.