An article from University of Oslo

Inside Guantanamo’s barbed wire fence

A Norwegian researcher on international courts and tribunals wanted to see what is going on in the Military trials at Guantanamo Bay. That turned out to be quite the challenge.

After the attacks on the USA on September 11th, 2001, the mandate of the American military base in Guantanamo Bay changed. From serving as a navy base, it quickly becomes the definition of the war against terror.

Hundreds of people have been sent to Guantanamo to be interrogated and detained under suspicion of participation in the attacks on the USA, or affiliation to Al-Qaeda.

Since 2002, at least 780 people from 40 different countries have been held captive on the American navy base.

As a researcher on international courts and tribunals, Kjersti Lohne wanted to see what is going on in the Military Commissions at Guantanamo Bay. Kjersti Lohne is a researcher at PluriCourts and Postdoctoral Fellow at the Faculty of Law, University of Oslo.

The Military Commissions at Guantanamo are specially established Military Tribunals that prosecute those detained at Guantanamo Bay.

But due to the strict regulations at the base, Lohne's trip proved to be challenging.

No room for researchers

During military commission hearings at Guantanamo, one single plane takes off towards Guantanamo Bay, from a military base in Virginia on the outskirts of Washington DC.

The plane carries all the different participants for the military commissions following 9/11, except the defendants. Selected families of victims from 9/11 are seated in Business Class at the very front of the plane.

With them, the judge, the prosecution and the commission’s support staff. Behind them is the defense, and in the very back, next to the toilets, there are seats for representatives from the media and NGOs. However, there is not a seat for researchers.

Consequently, Lohne also wrote an article, as an independent writer, for a Norwegian media house in order to get media accreditation. However, during her stay at Guantanamo she was open about her dual role as media and researcher.

Strict control from the military

Although Lohne had been given access to Guantanamo, she could not walk around freely. Together with the other observers, she was driven everywhere.

"The military were our drivers, but also our controllers," Lohne says

The different groups are also separated. They live in different tents (victims’ family members stay in apartments), eat separately, and are driven around the base in different cars. Members of the media are in one car, NGOs in another, and families of the victims of September 11th in a third.

"I was not allowed to ride in the NGO-car," says Lohne whose initial aim was to study how the NGOs at Guantanamo work.

When the trial starts, a curtain is drawn between the observers; representatives from NGOs and media on one side, and families of the victims on the other.

"In a way, the curtain also holds a symbolic value, marking the separation of perceptions regarding what the trial is about: justice for 9/11, or torture of the defendants while in US custody," says Lohne.

Throughout the duration of the trial Lohne was accompanied by a soldier who could peak over her shoulder to see what she was writing. Another journalist was reprimanded for scribbling in her notebook. Drawing is not allowed.

Everyday life at Guantanamo

Guantanamo Bay has – among other things - a McDonalds, an outdoor-cinema, and an Irish pub. In warm, Caribbean surroundings, those residing on the base could go to the beach, take a swim, or go snorkeling.

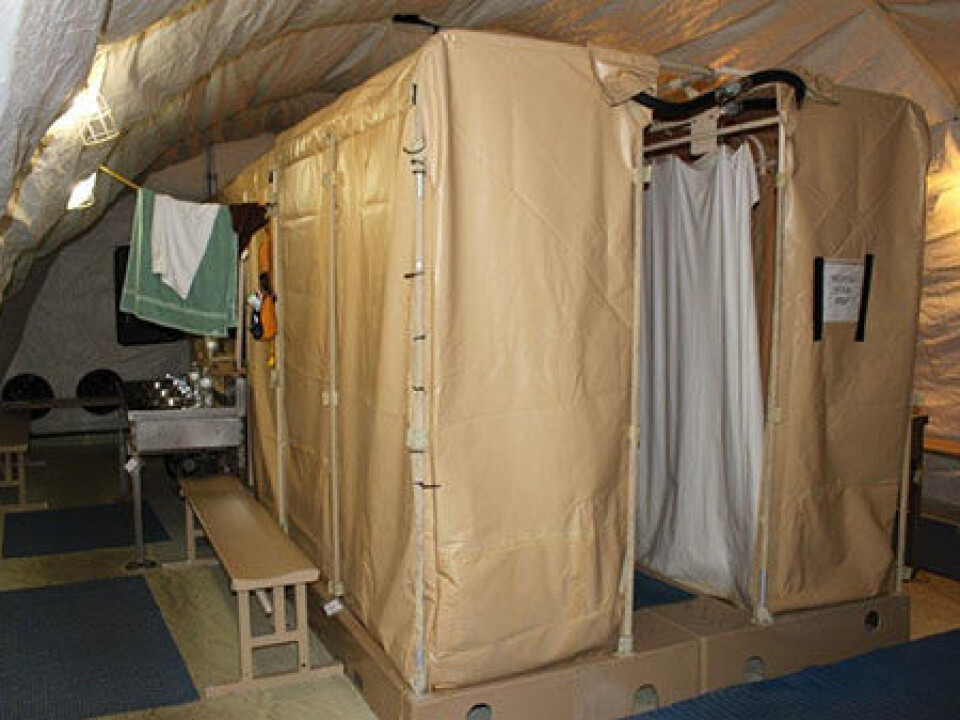

However, despite of this, there is little resemblance to the joys of Caribbean life, and a stay at the base is far from comfortable. The mobile showers were infected with fungus, and one of the issues being litigated in the military commissions during Lohne’s stay was concerns about high levels of cancer-causing toxins at Camp Justice.

The above mentioned conditions could quite easily be fixed, but as the base is considered to be at war, the temporary nature is upheld. It is after all a military base.

"You’re always a little bit on guard, says Lohne while sharing a memory of waking up from thunder in the middle of the night, and for a swift second thinking it is an explosion."

In many ways, the base operates as if it is at war.

"I guess it is supposed to feel this way," says Lohne.

After all, the American government is legitimizing the detention of prisoners and the use of military commissions on the grounds of being in an armed conflict with Al-Qaeda and its associates.

Consequently, the prisoners are to be considered prisoners of war, allowing for a prolonged detention without trial. Because of the interpretation of the conflict, the USA argues that the detainees are to be considered as un-privileged combatants, stripped of the combatant privilege – and protections - under international humanitarian law.

Guantanamo – Space of exception

"Guantanamo Bay operates as a «space of exception» says Lohne. It is a place that defines itself away from the normality of society and the universality of law, where people are placed outside the limits of the law."

"It is the ultimate alienation, or dehumanization," she continues and explains that a well-known definition of sovereignty is the ability to define the state of exception.

By researching the space of exception, one can say something about the intersections of law and politics, and how this friction shapes the constitution of our society.

As a researcher, Lohne had a very special insight. Fieldwork at Guantanamo Bay, as well as New York and Washington DC, will form the foundation for research on how civil society works with the Guantanamo Bay Military Commissions.

Wants to go back

Because it is difficult, costly, inconvenient, and uncomfortable to travel, and stay, at Guantanamo, civil society participation is limited. For example, to the extent that NGOs are represented, it’s through sending young interns who report back to headquarters in New York or Washington DC.

Despite the difficult access and relatively rough conditions for doing research, Kjersti Lohne wants to go back.

"It is an incredibly fascinating place – a microcosm of how order and the state of exception is negotiated in everyday practices."

Lohne is now working on three articles from her stay at Guantanamo.