An article from Norut - Northern Research Institute

Rock glaciers gain speed as permafrost thaws

The acceleration of rock glaciers in Scandinavia has been documented for the first time. It can be linked to the thawing of the permafrost in the north.

Scientists have long known that rock glaciers in the European Alps are moving faster than previously recorded. This is related to the thawing of permafrost and it is creating challenges for emergency preparedness in the Alps.

Due to climate change, the permafrost in the north has also started to thaw. And it could have major consequences for people as well as infrastructure.

Rock glaciers as climate predicters

Rock glaciers are unique landforms consisting of a mix of rock fragments and ice. They often look like a tongue-shaped section of scree. Rock glaciers are only found in areas with permafrost and a supply of rock debris, which usually comes from rockfalls and avalanches.

Using remote sensing data from the last 60 years, a Norwegian research group has found clear signs that previously stable rock glaciers are now accelerating.

The movement of a rock glacier complex on the Ádjet mountain in the Skibotn valley, Troms county, Norway, has received considerable attention in the doctoral project of Harald Øverli Eriksen at UiT The Arctic University of Norway and Norut.

“By comparing recent and historical aerial photos, we have documented that the glacier, which moved at an average of 0.5 metres per year in the period from 1954 to 1977, accelerated to around 3.6 metres per year in the period 2006 to 2014,” says Eriksen.

“Data from radar satellite from the period 2009 to 2016 showed that speed accelerated from 4.9 to 9.8 metres per year. The maximum velocity for one year was no less than 69 metres. It’s almost as if you can see the rock glacier creeping down the mountainside,” continues Eriksen.

Results suggest that the lower part of Ádjet is moving the fastest, and is in the process of detaching.

“In all likelihood, the accelerating rock glaciers are a visible result of the permafrost thawing,” says Harald Øverli Eriksen.

Researchers at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI) and the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET) have recently pointed out that thawing permafrost can cause more rock flows. In Svalbard, this is causing problems, including settling damage to buildings with foundations directly on permafrost.

Observed for the first time in Scandinavia

Harald Øverli Eriksen has recently published an article on the findings in the international journal Geophysical Research Letters along with co-authors from Norut, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET).

The study documents for the first time a unique acceleration of a rock glacier in Scandinavia.

“A lot indicates that the increased velocity of the rock glacier may be linked to an increase in temperature and precipitation, which has resulted in warming of the permafrost and increased amounts of water that has made the body of the rock glacier more unstable,” says Senior Researcher Ketil Isaksen at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

What are the consequences of permafrost in the north thawing?

“The social consequences and which measures should be taken are something that are outside our field of expertise. We have now documented that the thawing affects our mountain areas. It is now up to our politicians and operational authorities, such as the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE), to consider and implement any emergency preparedness measures,” says Harald Øverli Eriksen.

“We continue to follow developments by analysing radar satellite images. This data is very well suited for measuring ground movements,” adds Senior Research Scientist Tom Rune Lauknes at Norut.

Remote sensing provides unique information

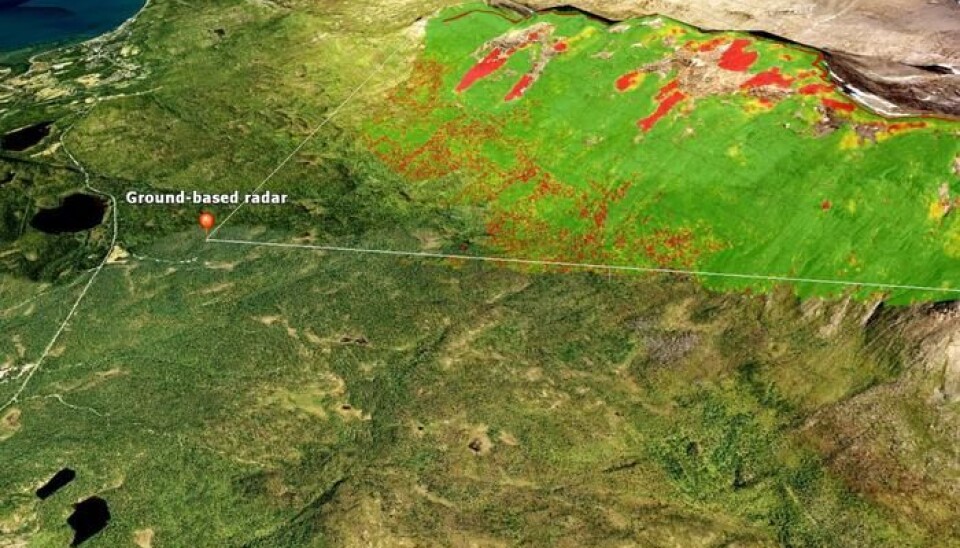

To study the rock glacier at Ádjet in Troms, the researchers used four supplementary remote sensing methods to collect data from a period stretching 62 years. They used old aerial photos of the glacier terminus, radar satellite images processed with SAR interferometry (InSAR) and offset tracking and data from ground-based radar, among other things.

“Using remote sensing from satellite and the ground enables us to follow this type of landform that is often found in inaccessible places with steep and dangerous terrain,” says Tom Rune Lauknes.