This article was produced and financed by The Research Council of Norway

Virus makes good E. coli bad

Some E. coli bacteria are harmless and some are dangerous from the outset. Then some become dangerous when they meet viruses. Scientists search for tools that will reduce this risk.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A group of Norwegian researchers has investigated whether viral infection can alter the properties of E. coli bacteria. At the same time they are trying out “disinfectants” that may reduce the risk of E. coli outbreaks caused by conditions in food-production facilities.

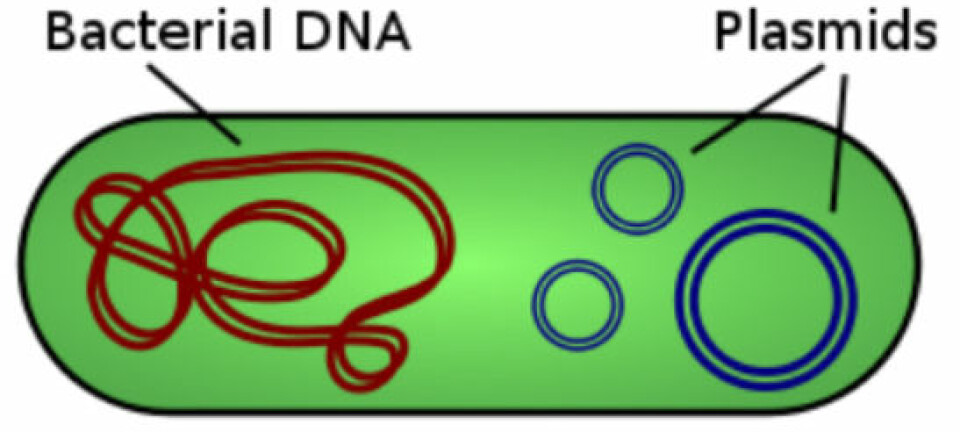

“It is well established that bacteria can obtain new genetic material from viruses. This may furnish bacteria with the genetic material needed to produce the toxins that make them more virulent and harmful to humans than they originally were,” says Anne Margrete Urdahl, a researcher working with E. coli-outbreak emergency planning at the Norwegian Veterinary Institute in Oslo.

Risk posed by biofilm

One source of bacteria in food is from biofilms that develop in facilities in food industries. A biofilm is an aggregate of many different types of microorganisms tightly packed together on a surface, encased in a self-produced layer of slime. This protects its contents from desiccation, disinfectants and the like, and they can survive in this state for a long time.

“Our project has researched the properties of isolated E. coli bacteria in biofilms,” explains Urdahl.

“We have found that E. coli from sheep can form biofilm at temperatures and on surface materials considered optimal for food production. Also, we have learnt how easy it is for different types of E. coli to survive in food-production facilities.”

Disinfectants of the future

Biofilm is one place where E. coli bacteria can infect each other with viruses that makes them more dangerous to humans. Blocking the formation of biofilm in food-production facilities may help to keep food from becoming contaminated with pathogenic bacteria.

“In order for bacteria to form biofilm, they must cooperate with each other. To cooperate, they need to communicate," Urdahl explains.

“If we manage to block this communication, we can prevent bacteria from forming biofilm where food is produced.”

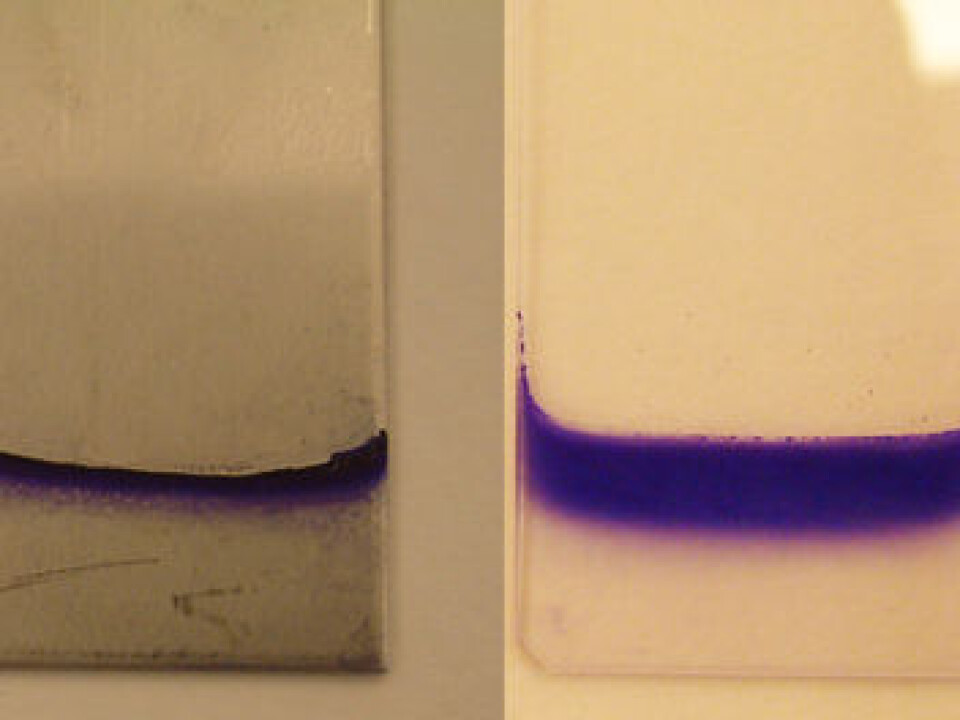

The scientists are currently testing whether communication can be blocked using substances called furanones. These substances were originally isolated from a type of algae.

"We have tested variants synthesised at the University of Oslo, and we see that they have some effect. Substances of this type may become the ‘disinfectants’ of the future," hopes Urdahl.

In the Research Council of Norway there is optimism on how these findings can help to resolve key long-term challenges to Norwegian food industries.

"But the thematic areas of safe food and a sustainable supply chain are very much a global challenge. This research is therefore also of importance in an international context,” says Maan Singh Sidhu, senior adviser in the Council's Food Programme, under which this research was partially funded.

Translated by: Glenn Wells/Carol B. Eckmann