THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

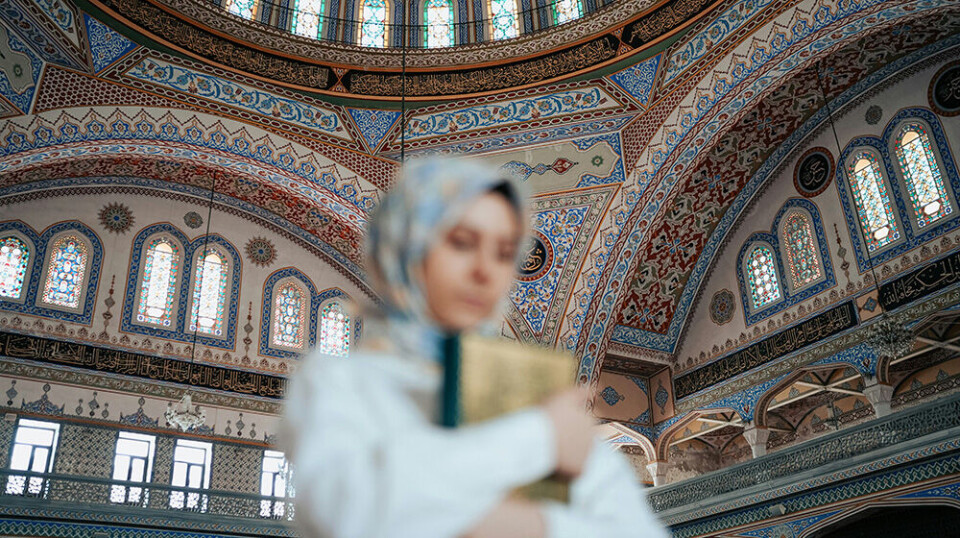

Islamic women's organisations confront Western feminism

They oppose international conventions for gender equality and distance themselves from Western feminism. The conservative network aims to promote women's interests on its own terms.

Several Islamic women's organisations accuse the United Nations of promoting women's rights and development projects that do not reflect the actual challenges in Muslim countries.

At the University of Oslo, Laila Makboul has researched the work and values of these women. It has been almost ten years since she discovered these conservative organisations.

“I wrote my doctoral thesis on female preachers in Saudi Arabia. Here, I discovered a larger network of conservative female professors who were active in transnational networks,” she says.

The network actively opposes UN-based gender equality agendas, such as the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). However, this does not mean they do not work for women's rights.

The networks imitate the UN

Makboul has found several prominent organisations and female Islamic activists who have been at the forefront of the network. The organisations have members from all over the world, and some women are members of several organisations at the same time. All of them are critical of feminism and values that they believe come from Europe and the West.

“The organisations aim to have an international voice. They collaborate across borders, organise international conferences, and even publish their own ‘international charters’ as alternatives to UN conventions. In many ways, it resembles how the UN operates,” she explains.

Makboul has conducted research in Egypt, Qatar, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. In all of these countries, she discovered mobilisation against international laws and conventions, particularly CEDAW.

“Many of my informants described the Cairo Conference as a ‘wake-up call’,” she says.

The United Nations International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 is especially known for putting women's sexual and reproductive rights on the global agenda.

"Subsequently, women's organisations saw the need to ally themselves, to stand together, and have a voice in the UN through activities such as lobbying,” she says.

Campaign against the UN's Sustainable Development Goals

Makboul has examined the mobilisation against the UN's Sustainable Development Goals. The organisations have criticised the goals for being dictated by wealthy countries in the north without considering the conditions in poorer countries in the south.

“When the UN adopted the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, the network launched a major campaign against them," she says.

While some of the women Makboul has spoken to have a nuanced view of the UN and believe they can collaborate on common issues, the most critical voices are uncompromising:

“This faction believes that if you give the UN an inch, they'll take a mile,” the researcher explains.

One of these women has become a sort of figurehead after being active in the UN system for over 15 years. She believes that nothing good comes out of the UN and is focused on exposing what she claims is a corrupt system controlled by Western leaders. Not everyone in the network agrees with her, and intense discussions are going on within the organisations about the best approach towards the UN.

Organisations oppressed by the authorities

The female preachers Makboul first became acquainted with in Saudi Arabia had hordes of fans, both young and old, women and men. The preachers supported the absolute monarchy of the royal family and enjoyed great freedom.

This was in 2015.

When she returned in 2022, the reality she met was completely different.

“The female leaders had suddenly disappeared from the public eye. Political parties have always been banned in Saudi Arabia, and now this form of religious activism was also being monitored and suppressed,” she says.

Makboul encountered the same situation in Egypt, where several former leaders had fled the country. This despite having had strong influence and support among prominent religious authorities at al-Azhar, one of the world's oldest and most prestigious Islamic educational institutions.

“I believe one reason why the regimes now see women as a threat is because they collaborate across borders,” she says.

After the Arab Spring, countries have experienced how quickly movements can spread. Additionally, some of the leaders in the organisations have had roles in the Muslim Brotherhood, which is now banned in the region. As a result, several have emigrated to Turkey and Qatar, where they have greater freedom for this type of activism.

“Recently, organisations in Indonesia and Malaysia have gained a more prominent role. This may possibly indicate that the centre of activism is shifting," she says.

Made Turkey withdraw from convention on violence

An example of the political impact of these organisations came in 2021. Through intense lobbying, alongside other local conservative organisations, they succeeded in making Turkey withdraw from the Istanbul Convention.

The Istanbul Convention is the Council of Europe's convention for preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Makboul explains that the Islamic women's organisations are against it for two reasons:

“One reason is that they believe these guidelines are dictated by the West and therefore controlled by concepts and definitions of gender and violence that are based on a European reality, which they claim is foreign to Turkish culture. The other is that they believe the language used presents values that are greatly respected in Turkey, such as the concept of honour, in a highly negative manner,” she says.

In Turkey, honour is often associated with the family, and how women behave within the family holds significance for the family's honour.

“Instead of the Istanbul Convention, these women aim to learn from positive experiences in other Muslim countries that they believe align more closely with their own values. Malaysia was particularly mentioned as a good role model,” Makboul explains.

Believe Europe holds definitional power

The critical attitude towards feminism has a historical backdrop in Muslim countries. In the past, feminism and activism for women's liberation were largely driven by elite women. Although many of them fought against colonialism, they often advocated for secular values.

In Saudi Arabia, for instance, it was not until the 1960s that access to education was made available to the broader population. The women who began organising themselves at that time often opposed secular feminists, whom they believed did not represent the average Muslim woman.

“Some of the women also view feminism as an example of intellectual colonialism, believing that former European colonial powers still hold the power to define gender and equality,” says Makboul.

Another issue these Islamic women have with Western feminism is that, to them, it is a secular ideology that prioritises individual self-realisation and human-centred values. They see their own worldview as opposed to this, where God and the collective play a central role in interpreting both men's and women's rights and duties.

“They believe that both men and women best fulfil their responsibilities and rights when they have complementary roles. Therefore, in many ways, they aim to preserve traditional gender roles,” Makboul concludes.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family