THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

Is there always a contradiction between morality and self-interest?

If we accept the conflict between moral obligations and personal interests, it becomes easier to find ways to live with it, according to philosopher Mathea Slåttholm Sagdahl.

Should I take a week's vacation and fly to Lanzarote because I'm so tired and stressed, or should I rather stay home considering the CO2 emissions the flight causes?

Being able to identify which considerations and actions that are morally relevant, and which are not, is central to moral philosophy. But what if there are other types than moral considerations that play in to what one should do?

This is a question that philosopher Mathea Slåttholm Sagdahl addresses in her research.

What is right and wrong

What Sagdahl and the other researchers involved in the project do is delve into the intricate interplay between moral obligations and personal interests.

This is not something new, but a question philosophers have been dealing with since antiquity. First a clarification:

“What does moral philosophy deal with?”

“The social sciences and psychology explore morality as a phenomenon as well, but are more interested in looking at how people act and think with respect to morality and ethics. When philosophers talk about ethics and moral philosophy, it's about trying to find answers to normative questions: what is right and wrong, and what one actually should do,” Sagdahl says.

Failed to prove the conflict

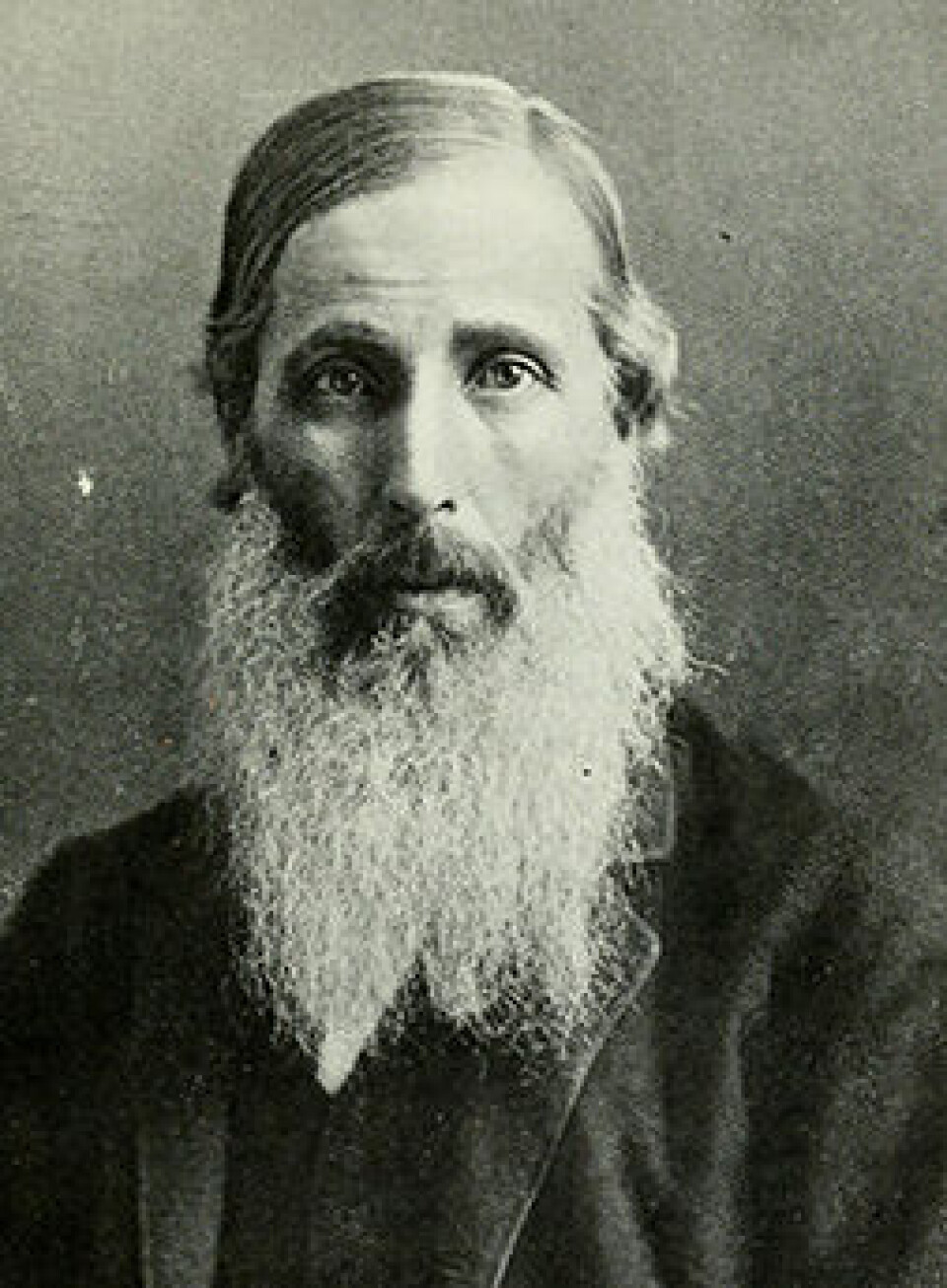

The title of the project, The profoundest problem in ethics, is a phrase taken from the English philosopher Henry Sidgwick (1838 –1900). He wanted to find a rational basis for morality, and he carried out a systematic review of moral considerations in the book The Methods of Ethics.

Sidgwick ended up with a fundamental paradox: He failed to prove that it is more irrational to act in favour of oneself than out of morality.

“The fact that he failed to prove this, is the starting point for this project and much of what I have worked on. Rather than trying to explain away this dualism and conflict, I want to defend that it exists,” Sagdahl says.

She also addresses this in her book Normative Pluralism: Resolving Conflicts between Moral and Prudential Reasons published in 2019.

Looking at reasons

Sagdahl focuses on the reasons behind our actions rather than moral principles.

“Reasons has long been a somewhat obscure part of ethics. But over the past decade, this part of philosophy has gained much more attention. We should look closer at reasons because they are central to how people act and think ethically,” she says.

Simply put, ‘reasons’ are considerations that speak in favour of a particular action, attitude, or feeling.

She provides an exemple: The washing machine breaks down. Instead of fixing it, you want to buy a new one. The motivating reason is that you need a new machine quickly because the laundry is piling up.

There are also other reasons, such as normative or justifying ones. And it's those reasons that moral philosophy is most concerned with. This line of reasoning might lead you to argue that the washing machine ought to be repaired out of concern for the environment.

Is there an overarching value?

"A common assumption within the philosophy of reasons is that there exists an overarching value, and that different considerations are weighed against each other with respect to such a value,” Sagdahl says and continues:

"However, there is a lack of systematic proposals as to how such weighing should be carried out. We are trying to move away from the idea of weighing, and to find other methods that enable us to incorporate these conflicting considerations into our lives.”

She is sceptical of the idea that there is an overarching value that can unite these considerations. Therefore, they want to problematise the weighting model in the research project.

“For some it may seem disappointing that a philosophical examination of our reasons cannot give us unequivocal answers to what we should do, but this can also be seen as an advantage. We might argue that this reflects the normative reality we operate within,” she says.

Can be solved politically

Sagdahl argues that the interaction between self-interest, and what is perhaps seen as morally right for society, is also a political question.

“Many conflicts between morality and self-interest can be resolved through the way society is organised. If the social structure provides us with better incentives to cooperate and think about the common good, there will be fewer conflicts of interest,” she says.

Sagdahl explains that for the climate and environmental crisis, for example, it could lead to the values and attitudes of the individual changing. This way, acting in accordance with the environment may better align with one's self-interest.

Some of the researchers involved in the project plan to explore environmental issues.

However, in the project, they mostly look at the individual. A relevant question to explore might be: Can ethicists tell you what you should do?

It has been assumed that moral considerations take precedence and trump self-interest. But this may involve the sacrifice and limitation of personal freedom.

If an individual is not faring well, can it still be considered good for the collective?

“Suppose that you are a person with many obligations and relationships to people who depend on you. But suppose also this life is not good for you, and that you feel that you are obliterating yourself. If you stop, you break with the obligations you have to those around you and let them down. However, it does not seem obvious to me that the consideration towards others should take precedence over your own needs,” Sagdahl says.

Self-interest can be morally correct

Self-interest may sound more selfish than it is. We have people, pets, and maybe also places in nature that we care about. This is also part of our self-interest. These interests are not necessarily in conflict with morality.

“In ancient philosophy, being a virtuous person also entailed being good to oneself. This is a thought that I share to some extent. Both in terms of morality and one's own well-being, there are good arguments for this in order to avoid becoming self-centered, brutal and cynical,” Sagdahl concludes.

Reference:

Sagdahl, M.S. Normative Pluralism: Resolving Conflicts between Moral and Prudential Reasons, Oxford University Press, 2022. ISBN: 9780197614723

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”