An article from KILDEN Information and News About Gender Research in Norway

Beaten by their wives

Violence is neither a women’s problem nor a men’s problem, it is a human problem. But men who are physically abused by their partners don't talk about it.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

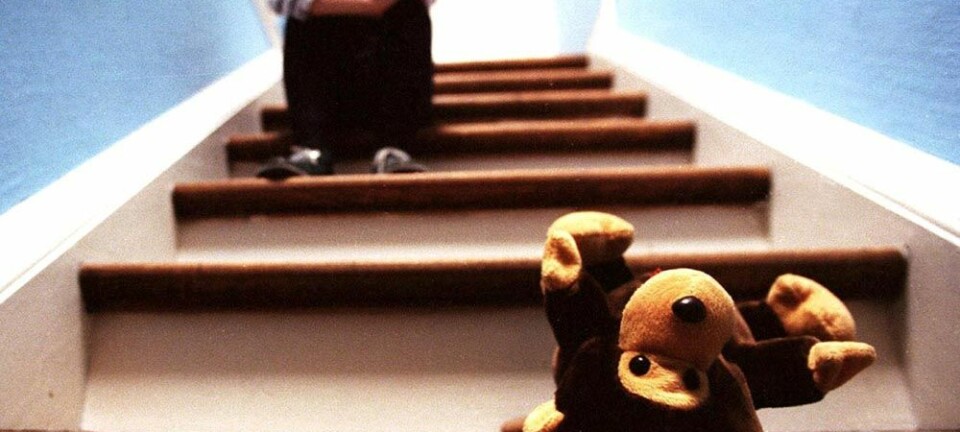

“…so that I fell on the floor, and she sat on top of me and hit me in the face. The children were watching and started to cry.”

This is a statement from one of the ten men interviewed by Tove Ingebjørg Fjell about their life with a violent partner.

Fjell, a professor of cultural studies at the University of Bergen, recently presented her research project “Always walking on eggshells”, which she plans to complete this spring.

Violence happens to both men and women

It was extremely difficult to find someone who would talk, admits Fjell. Many of the men feared their wives would find out and do something, for instance leave with the children.

But when they came to the interview, Fjell almost didn’t need to ask any questions as the stories just poured out of the men.

Fjell thinks the men’s stories about violence by their partners show how important it is to downplay the focus on the gender dimension.

"We have a biased view of the man as the perpetrator on the one hand and the woman as the victim on the other. We need to understand that violence involves human beings,” she says.

"You just accept it"

“I don’t remember the first time. It’s a little strange. It’s as if you lived in a place where it was very dangerous to walk in the streets and every day someone came and beat you up. But you survived and it became a part of your daily life. You go and buy vegetables at the store, but you don’t remember what vegetables you used to buy two years ago. It’s like that with violence too. You just accept it and hope that it passes.”

This is how one of the men Fjell spoke with described the experience of being the victim of violence. It is a common, gender-neutral description. This similarity between men’s and women’s stories about intimate partner violence is one of the main findings in Fjell’s study.

Men’s stories are reminiscent of what we read in the traditional literature on wife abuse, she explains. Men are also beaten, hit on the head with an ashtray or threatened with a knife by their partners. Most of them tell about episodes of psychological violence, such as a wife phoning constantly to check what her husband is doing.

"Or the partner makes threats. She might threaten to file for divorce if her husband has contact with his family. Some women threaten to murder the children,” says Fjell.

Men don't call it violence

During the interviews Fjell found some common features that she believes are typical for men who are victims of intimate partner violence.

According to her, men are able to give concrete descriptions of violent situations, but they don’t call it violence. They often say that they could have thrown their partner to the ground; they just didn’t do it. She puts this tendency in the men’s stories in a historical perspective.

“The concept of violence is changing all the time," says Fjell. "If the men had told the same stories 60 or 40 years ago, it would not have been called violence, but today we recognise it as violence. Quite simply, it takes time to acquire a language that describes the same action in the same way for men and women.”

She also explains that the men she interviewed have fewer stories of gross violence than you would get from female victims of violence. The men also have less fear of being killed. They might be afraid of being seriously injured, but they are not afraid of being murdered by their partners, like some women are.

Men in crisis centres

A common feature of the men Fjell interviewed was that they were very reluctant to seek help. None of them had contacted a crisis centre, but they did not necessarily rule out the possibility.

One of the men said that he would have gone to a gender-neutral centre: “I think very many women who are abused would benefit from seeing that it is not just women who get hit. We could help each other.”

Wenche Jonassen has for many years studied Norwegian crisis centres. She is a sociologist and researcher at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies (NKVTS). Recently she looked into the situation in the wake of the new Norwegian legislation on crisis centres, which in 2010 required all municipalities to provide the same services to men and women.

Jonassen admits that she reacted with scepticism when she first heard about the new crisis centre legislation. She thought that men could certainly have a need for counselling and advice – but protected overnight accommodation?

“At that time I could only imagine female partners. It turns out that just as many men who use the overnight accommodation at the crisis centres are victims of violence by male partners, and yes, they do need the crisis centre services,” says Jonassen.

Men use the crisis centres for a variety of reasons

Last year Jonassen decided to conduct a pilot study to look into the experiences of the crisis centres after they had been offering their services to men for a period of time. She phoned eight large crisis centres and did an informal survey.

Out of the eight centres she contacted, only five of them provided the same services for men as they did for women. Of these, only three centres had had men living there.

The survey revealed a variety of reasons why the men contacted the centres:

Several of the men came because they were being forced into an arranged marriage. Other reasons were psychological harassment by women or by homosexual spouses. Ethnic minority men also sought out the crisis centre due to cultural conflicts with their families.

The survey showed that fewer men than women sought out the crisis centres due to physical violence.

Like Fjell, Jonassen concluded that there are great similarities between men and women who are victims of violence.

“The staff members at the crisis centres have a great deal of knowledge about female victims of violence, and this knowledge is entirely applicable to men who are victims of violence in intimate relationships," says Jonassen.

But some additional challenges have emerged since men have started using the crisis centres.

"For example young men with minority background have used the overnight accommodation due to their families’ reaction to what is viewed as unacceptable behaviour. This could be that a son has spent time with people from other cultural groups or that he does not practice his religion,” says Jonassen.

Men believe they are the only ones

One of Fjells informants was disappointed that when he told his regular therapist about the violence he experienced at home, she responded by mistrusting him and downplayed his experience. Many of the men Fjell interviewed refrained from telling others about the violence because they were afraid of not being believed. Shame was also part of the picture.

“Men contribute to keeping their stories secret by not talking about them. And the public system of services helps maintain this secrecy by not acknowledging that men can be victims of violence,” says Fjell, who calls for a debate that brings violence against men into the open.

Another question is whether there is sufficient interest in this problem within the health services.

"Men often believe they are completely alone with their experiences. Many years can pass before they develop an awareness of what they have been subjected to," explains Fjell.

“We need the same kind of discussion that we had in the 1970s about violence against women. We don’t need to spend 30 years discussing intimate partner violence against men, but it will be necessary to spend some time and resources on shedding some light on this topic,” says Fjell.

Numbers unknown

Studies of male victims of intimate partner violence are relatively new in Norway, and Fjell and Jonassen both insist that much work still remains.

Jonassen adds that men now have access to crisis centres for the first time, and it is important to find out what they are struggling with, what type of services they are seeking and what differences there are between men and women in this area. She wants to conduct a study on this in the near future.

“Most of the men in my study are in their forties, but violence has no age limit," says Fjell. "Studies can be done that address the entire generational spectrum, including older women and their use of violence. How often does this happen? We know very little about this today.”

-----------------------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Connie Stultz