An article from University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway

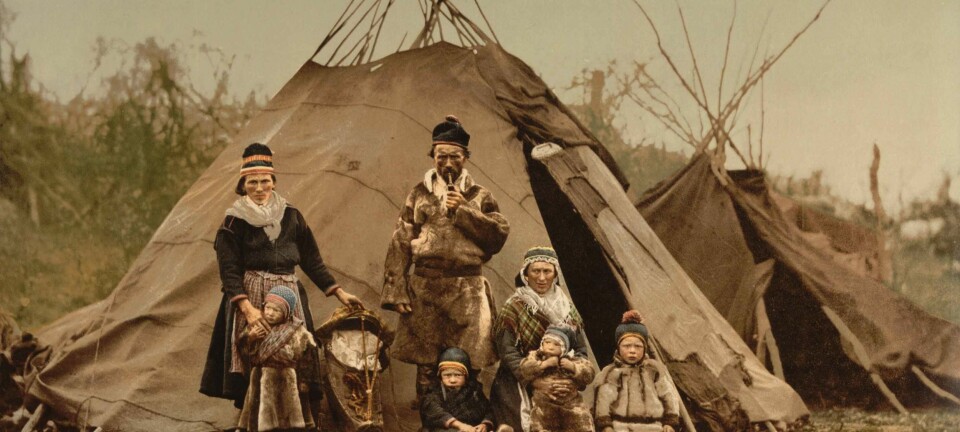

Sami national strategists

The early indigenous Sami opposition at the beginning of the 1900s was not just composed by individual voices on limited political and cultural issues. They challenged established policies and conceptions, with partly alternative social analyses.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Isak Saba, Anders Larsen and Per Fokstad were national strategists for the Sami - the northernmost indigenous people of Europe.

“They felt that their political and ideological project was a part of the Norwegian nation building. It was a project against hegemony, a project that represented an alternative to the dominant social order, which occasionally broke through and managed to establish itself in the national debate," says Ketil Zachariassen.

"Even though the strategies did not succeed with the Sami's demands at that time, it was still fully a part of the nation-building process.”

Longitudinal analysis

Zachariassen recently defended his dissertation in the Department of History and Religious Studies, which deals with the Sami political opposition in Finnmark between 1900 and 1940.

“I have extended the research field by including cultural, political and scientific perspective in a longitudinal analysis over forty years. It is not enough to look at school policy discussions and results of these discussions in the Storting if you want to understand the Sami opposition. In what other venues were the Sami able to break through? Newspapers, fiction - and scientific surveys and research must also be included," he says.

"The backdrop is of course Norwegianization, but I was interested in the Sami actors and how they argued - in the Sami language debate in Finnmark, the Norwegian-language debate in Finnmark and in the national debate.”

Two phases

The political mobilization of the Sami in the first half of the 1900s took place in two phases in particular, from 1904-1912 and from 1917-1924.

In the first period, Isak Saba from Nesseby, a Member of Parliament, and Anders Larsen, a newspaper editor from Kvænangen, were in the lead on the issues – the parliament election, Sami as the language of instruction in schools and their own Sami language newspaper, Sagai Muitalægje.

“They gained ground because they succeeded in creating an alliance with another project against hegemony: fish farmer socialism in the labour movement,” says Zachariassen.

The first Sami congress in Trondheim in 1917 marks the start of the second phase. With Elsa Laul Renberg, a southern Sami, as the spearhead, a more unified domestic Sami movement emerged - with Sami from both the north and south, and a national Sami organization, Sámi Sentralsearvi (Sámi Central Association).

This organizational mobilization nevertheless broke down in 1921.

“Then ideological and cultural issues were put on the agenda, first and foremost by a teacher and later principal and mayor Per Fokstad from Tana, who propelled the Sami opposition forward more or less by himself.”

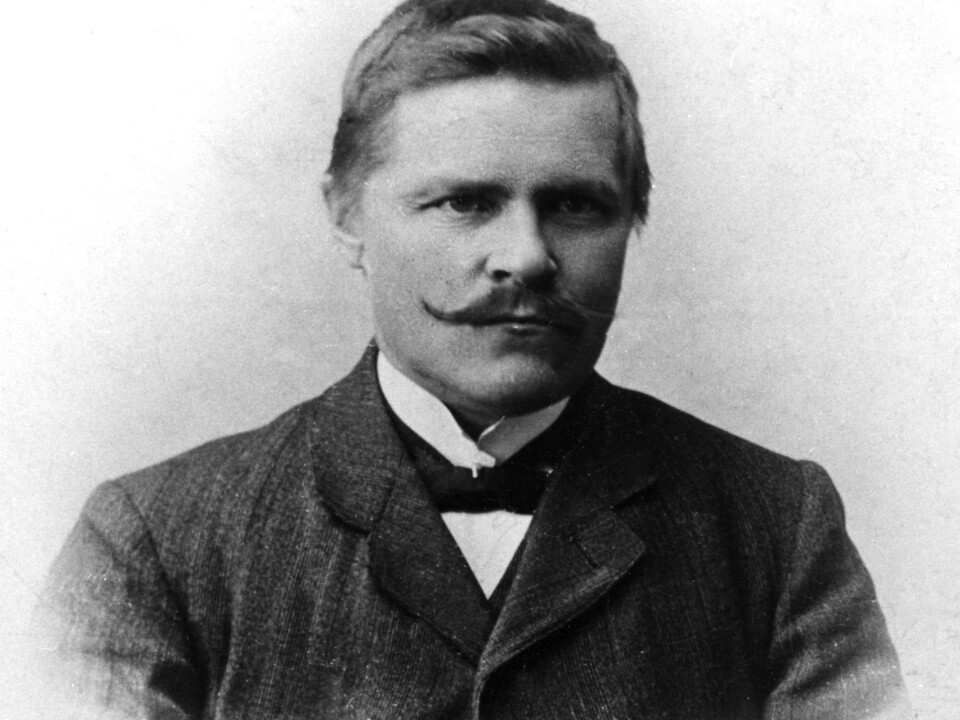

Per Fokstad

Per Fokstad was a man before his time. In the early 1920s, he published a series of articles on the basis for the Sami language, culture and society, and prepared school plans that were based on a societal organization founded on linguistic and cultural pluralism.

He believed that the Sami could also be a civilized nation - and not "just" primitive people - and that the Sami people could be Norwegian without losing what it was that made them Sami.

"Of course Fokstad believed that the Sami had to learn Norwegian," says Zachariassen.

"But he was concerned that they should also have the right to learn their mother tongue - not only because it was a useful auxiliary language, but also because it was a right and a value in itself. A separate people had to have its own language."

This was a modern way of thinking, which Fokstad had developed in part as a result of studying abroad for four years -- between 1917 and 1921, he was in Denmark, England and Paris.

Many counter-arguments

The demand for native language training was met with political, linguistic and educational counter-arguments, and not least, researchers used the issue of security policy as one explanation for the opposition: Assimilation and becoming Norwegian were both seen as important in ensuring loyalty to the new nation.

“But even if Fokstad’s arguments concerning native language instruction did not result in a breakthrough in the 1920s, he laid an ideological foundation that was later was picked up by the Sami movement after the war, and Fokstad remained a leading Sami actor all the way to 1970,” says Zachariassen.