An article from University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway

The Sami never sold their souls

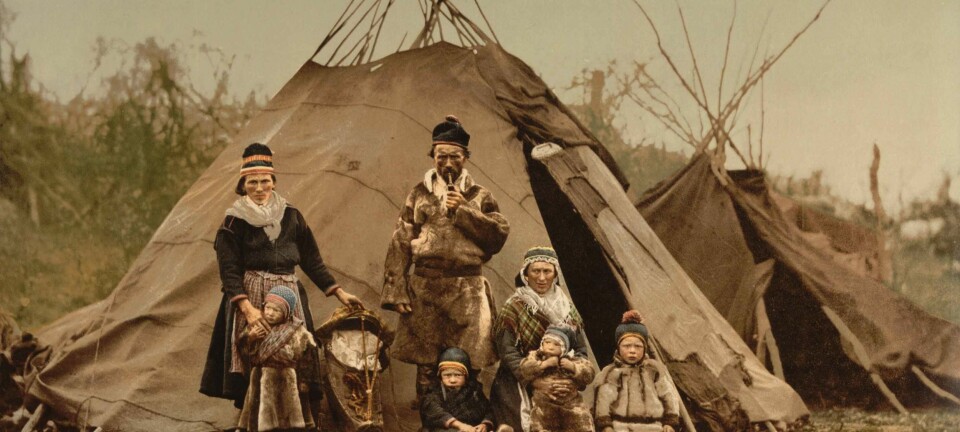

From the middle of the 1800s to the end of the Second World War, it was possible to see living Sami people on exhibit.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Today, live exhibitions of people are seen as a blast from a past, and as something that feels foreign to us now − as one of many historical abuses that society imposed on those who were different.

“It is quite wrong to see this as a history of unilateral exploitation,” says archaeologist Cathrine Baglo.

Baglo recently defended her PhD dissertation, Gone astray? Live exhibitions of the Sami people in Europe and America.

She is quite critical of the image of the Sami as victims, which is the image that is commonly associated with this practice. She believes this simplistic view over time has hindered research on the topic.

"It means that we have basically written the phenomenon itself off in advance, which has made any research or interpretation of the matter seem unnecessary,” says Baglo.

The fact that the exhibitions were often held in zoos or animal parks has been explanation enough for the interpretation for posterity.

She said no one has examined the practice in depth to see what the conditions were.

The fact that the Sami stayed in zoos, for example, was actually just by chance, and was due to the fact that this was the exhibition space owned by one of the largest concessionaires in the region, the German Carl Hagenbeck.

The zoo, with its distinctive combination of gardens, exotic architecture and live animals imparted some of the overall exotic experience Hagenbeck and many other exhibitors wanted to convey.

“There was never anyone who tried to portray Sami as if they were animals,” she adds.

She also noted that many Sami preferred to stay in zoos, because they were veterinarians there, and their reindeer were given proper care.

In Paris in 1933, for example, the Danielsen family was offered a place in a hotel, but they preferred to stay in the Bois de Boulogne, where the zoo was located, along with their reindeer.

Work contracts and first-class hotels

The exhibition of Sami people was part of a larger trend in the Western world that grew during the 1800s.

Representatives of foreign nations, and from what would eventually be thought of as "primitive" peoples, were brought to Europe and America where they showed visitors what their everyday lives were like.

These presentations were held at major world's fairs and expositions and as travelling exhibits in zoos, amusement parks and at circuses.

Baglo has examined and surveyed information from roughly 400 Sami who participated in these exhibitions between 1822 and 1950.

By thoroughly examining the stories of everyone who was on 'exhibit', and by taking an empirical approach, Baglo have found that the Sami had many different incentives for allowing themselves to be put on exhibit, and that they made something of these many different experiences.

“In addition to earning money, many learned foreign languages, which laid the foundation for their later education,” she says.

“They had contracts that governed their work assignments, pay and travel expenses and the medical supervision of both people and animals."

At the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, for example, a group of Southern Sami negotiated a contract that included a clause that provided them accommodation in first-class hotels during the exhibition.

Sad stories, too

But there are also stories of exploitation and poor working conditions, of course. The contracts were not always adhered to, and the conditions were sometimes not in line with what many had been led to expect.

Baglo concludes, however, that whenever you are dealing with living human beings, they will always be involved and will have an influence on the way they are represented − in contrast to wax dolls that came to museums in later times.

The living exhibitions were always characterized by an exchange of interests between the various individuals involved, and Baglo thinks the most accurate way to perceive the exhibitions is as a resource for everyone involved.

There was no lack of critical voices during the period, however, and also from the Sami side.

The question of what and who was a real Sami, and how the Sami people should be represented were central issues. Some Sami participated in the exhibitions out of economic necessity, while others were almost full-time professional actors.

"Many gifted Sami transformed this experience into a means of making a living. And we should also not underestimate the power of these exhibitions as an early forum for indigenous people.”

At the World's Fair in Chicago in 1893, the South Sami Daniel Mortensson stood side by side with the Sioux Indians, something that probably led to subsequent events, such as the Sami political movement in the early 1900s.

Transformed into a tourist industry

Living exhibitions were held over the whole of the Western world, yet they show a fascinating similarity in practice, according to Baglo.

She said there were similar kinds of exhibitions in different areas over a long period.

The high point was between 1880 to about 1910, with the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris. During this period, the practice was seen as a legitimate way to disseminate scientific and cultural information.

“But during the next 10 to 20 years, the exhibitions fell in stature, and the big exhibitioners were quickly criticized," says Baglo.

Around 1930, up until about 1950, the exhibitions ended, but she thinks there was a gradual transition to the ethnic tourist industry we see today, that the Sami themselves control.

Something other than a "Freak show"

The so-called "freak show", where people with various physical malformations were put on display, was also a child of the same times as the exhibition of the Sami.

"But these were something altogether different,” explains Baglo.

A freak show is a display of individual differences, while the exhibitions of the Sami and other aboriginal people was a display of collective differences. An accurate representation of cultures, which showed normal family life, was generally the central goal for many exhibitors.

“The Sami themselves participated in creating the scenarios. They, in no way, sold their souls, but sold exhibitions of their lives and culture, exhibitions that they themselves, through being there, helped to shape,” concludes Baglo.