THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Slow reading and breaks can fuel your imagination

New research suggests that short breaks help you think more critically and creatively about what you are reading.

Perhaps you read a lot every day. At a brisk pace and with a good flow, you scan page by page and capture the most important aspects of the text.

According to Sarah Bro Trasmundi, this is a useful way to read when the goal is to gather information quickly and find answers to questions.

“But we also want reading to spark creativity and foster imagination and critical thinking,” she says.

Trasmundi’s field of research is cognition and reading. She has studied people’s reading methods and found that there are diverse ways of reading, even if the task and the text are the same.

Yet in one study, she discovered that critical readers had something in common: They took many breaks while reading.

“It was as if they took the time to examine things in the text and reflect on what they read, in a very different way from when they were absorbed in the reading” Trasmundi says.

The value of creativity and imagination

Her research has led her to hypothesise that breaks may have a valuable function when we read.

“Breaks have been seen as a disturbance in reading, but in our study, we could see that this was not the case for the imaginative readers. In general, the ones who took multiple breaks were extremely motivated, committed, critical and reflective,” she says.

She anchors this hypothesis in Japanese philosophy and especially with reference to ‘Senu-Hima’, a concept from the Japanese Noh theatre that means ‘intervals of not acting’.

The term refers to pauses that act as a transition phase that ruptures the flow of prediction. These pauses are thus not viewed as empty, but rather as an opportunity for something new to happen because they force the reader to actively take a stance beyond what is predicted.

“Creativity and imagination are important. Society is built on new ideas and new ways of thinking, organising, communicating, and so on. And that means we have to be able to think in different ways than those before us,” she says.

In Japanese culture, breaks are crucial for skills such as creativity and imagination, but they also relate to well-being.

“The slow down mechanism enables us to engage with things in meaningful and critical ways, because we question norms, rules, and we do not just go with the flow. We allow time and space to impact our thinking in ways that increases the feeling of agency. That feeling can increase well-being and make us open-minded in our opinions and assumptions,” Trasmundi explains.

Meaning arises during reading, not only afterwards

When looking at imagination, Trasmundi works at the intersection between cognition and language; her aim is to examine what happens when the reader makes sense of the text they are reading.

She believes that when we read, we ascribe meaning to the text along the way, and that imagination does not necessarily come into play only after we have finished reading.

“There may be small impressions in the text that make us feel something about it, such as syntax, peculiar words, or something that reminds us of something. Impressions we usually forget when we’re done reading,” Trasmundi says.

Creating openings that leave room for critical thinking

“Today, we teach children to read first, and then give them methods to unlock the text. But that’s analysis, not reading, or one could say a kind of reading the already read” Trasmundi points out.

She believes reading goes beyond understanding what words mean and extracting information.

“It also means engaging with what you read in interesting ways and using it for something valuable, for instance when a reader starts reading aloud, or repeating a word or passage several times to feel comfortable with the text,” she says.

But this way of reading is more time-consuming than scanning the text to extract information.

“To be critical, you must reflect, think and engage with knowledge beyond the text. To do that, you have to create openings while reading that allow you to simultaneously absorb the content of the text,” she explains.

Thinking several thoughts at the same time

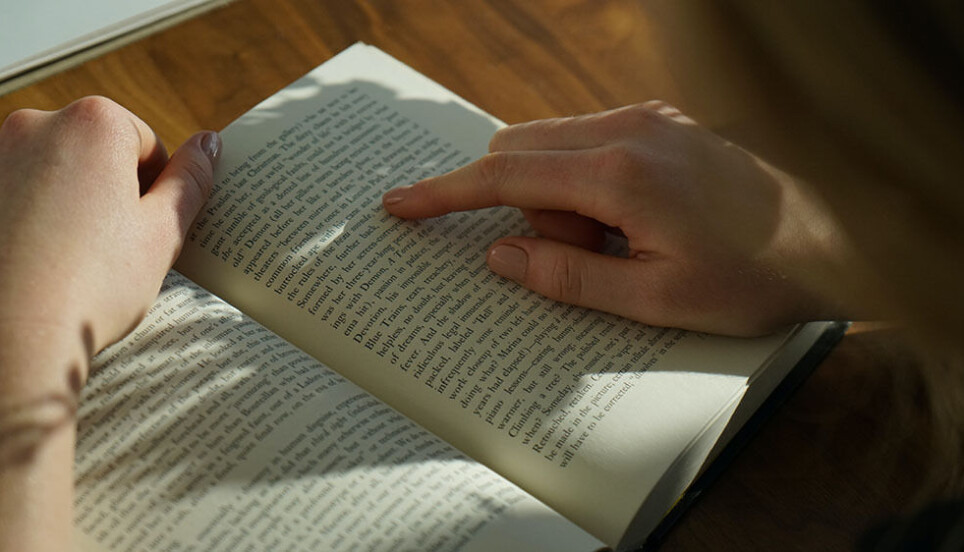

In the study, Trasmundi saw how the imaginative readers created temporal room while reading by holding their finger somewhere in the text, or by freezing to hold on to the ideas that arose along the way.

“It’s commonly believed that people read quietly inside their heads, but we observed that reading is a very physical activity,” the researcher says.

She sees the body as a cognitive scaffolding resource that can help provide structure to several simultaneous thought processes.

“We use gestures to hold on to something while exploring something else. The body helps us out when we engage in several tasks at once,” Trasmundi says.

Calm down to open up a space for the imagination

The current tendency is that the new generation of readers’ reading skills are in decline and many young people dislike reading. Trasmundi’s starting point was therefore to explore the reading patterns of people who do not like to read.

“In the United States, the curriculum has changed so that students are presented with shorter texts and fewer complex and philosophical texts in higher education. This adjustment tendency is a result of a decrease in reading skills,” Trasmundi says.

Her goal is to develop methods that increase the joy of reading for students. This involves showing them that the value of reading goes beyond the ability to answer exam questions.

Trasmundi believes that changes in our approach to reading starts in primary school. When children practice reading, the focus should be on enjoyment, with an emphasis on imagination and creativity.

“When children first learn to read, we see that their reading is full of interruptions and rich in imagination. They often go in and out of the narrative and link what they read to all sorts of ideas, events, and emotions. But then, they are constantly reminded to go back to the text and to focus and concentrate. But by focusing on reading as a narrow, decoding process, we take away the joy of reading from the very beginning,” Trasmundi says.

She adds:

“Of course, we should train speed, fluency and vocabulary, but there should also be room for imagination.”

Reference:

Trasmundi et al., Human Pacemakers and Experiential Reading, Frontiers in Communication, 2022. DOI: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.897043

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

"Fascism must be countered with knowledge"

-

Asian leaders on social media: Share stories about their love lives, offer advice on radio shows, and play with cats

-

Demonstrations: Meeting face to face may be more important than ever

-

"Everyone knows it, everyone’s seen it. Most people have a perception of nightlife chaos”

-

Music in film and TV: “It's a form of manipulation”

-

Can you take antidepressants while pregnant?