THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

A sudden, liberating thought pops into your mind – but is it really yours?

Do you deserve praise and recognition for good ideas that seemingly just pop into your mind? Yes, philosopher Francesca Secco believes. She wants to provide nuance to what can be considered an action.

Creativity can manifest itself in so many ways. It often requires concentration, effort, and hard work over a long period of time. However, there is no guarantee that you will come closer to finding a solution to your problem.

“I think we all struggle to come up with new ideas from time to time. Everyone has experienced having writer's block that we see no way out of,” Francesca Secco says. She is a philosopher at the University of Oslo.

However, sometimes a new idea just seems to pop into your mind.

“This is something that I constantly experience as a researcher. I can be struggling to think of a good idea for an article or a presentation, and just have to let it go,” Secco says.

But then it comes to you while you're doing something completely different, and while your attention is seemingly somewhere else entirely or nowhere at all – a sudden, liberating thought that may perhaps take you further in your creative work.

We should be praised for thoughts and ideas

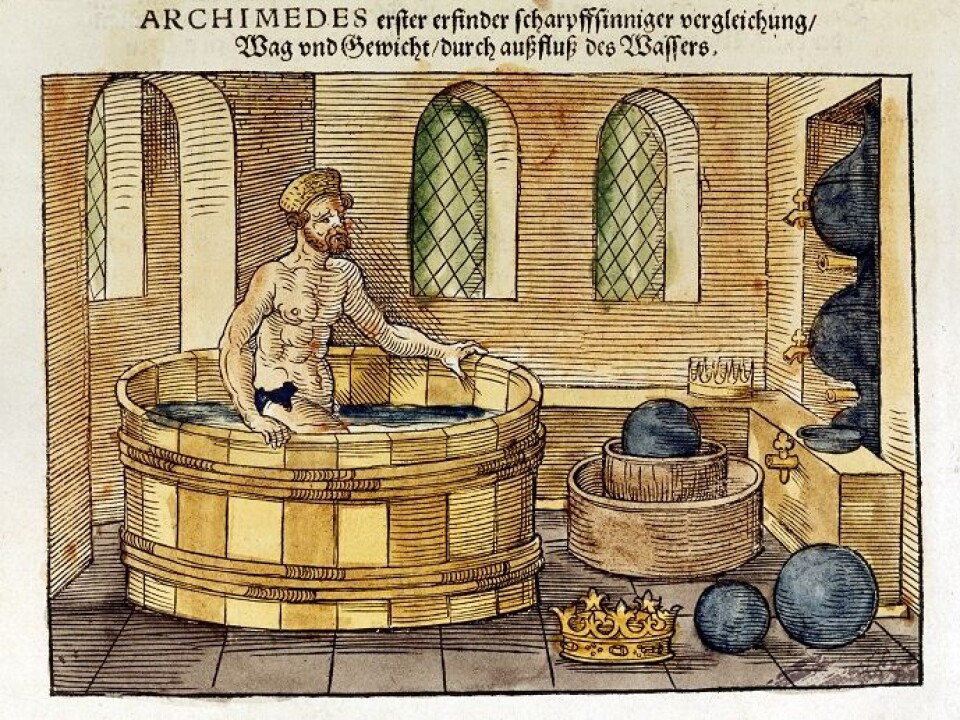

Archimedes in the bathtub and Newton under the apple tree are classic examples. Artists, writers, and scientists, too.

But it could just as well be a carpenter or a plumber facing challenges in building a new house. Or a sudden idea about how to set the table for Christmas dinner.

In the past, credit might have been given to a muse or to God. But Secco argues that we should in fact praise people who come up with ideas in this manner.

Even if they seemingly pop into our heads without warning.

“The fact that we, as individuals, come up with the idea is something we should acknowledge and praise because it happens to us and not to others. The reason that we are in that situation is that we possess the necessary knowledge, interests, and experiences. It is something that can only happen to us,” Secco says.

Furthermore, the creative work is not complete and finished even if a good idea should pop up in this way.

“The creative process obviously goes far beyond an initial thought. In the case of a researcher, for example, a new idea is not enough. It also has to be tested and potentially proven. But that is something we do with intention and purpose. We can control that part of the work,” Secco says.

It is this distinction between intention and idea that interests Secco, particularly what it could mean for what the field of philosophy refers to as action theory.

What you do – and what just happens to you

An action is traditionally defined as something we do with purpose and intent, as opposed to things that simply just happen to us.

Examples of the latter can be getting hit by a ball or, worse, by seagull droppings while sunbathing. Our digestion or a bout of hiccups are not defined as actions either, because these are things that our body does automatically.

But what about these thoughts that seem to pop into our minds without us actively seeking them? They are not intentional. But does that mean they are not actions?

“I don't consider the idea itself as an action. But I do think that the process that gives rise to the idea should be considered an action. It is an action because it is so closely connected to the person who has the idea. It reflects this person's interests, past experiences, and knowledge,” Secco says.

She is therefore of the view that action theory should have a more nuanced view of what an action can be, and it shouldn't be restricted to intentional actions.

“I am not trying to push back against the existence of intentional actions, but I would argue that this is just one way to capture the close relationship between a human being and their actions,” Secco says.

Is reading an action?

Another example of how actions can be more than what we do intentionally is what happens when we see a word or a sentence in front of us.

“When it comes to reading, this is not something you can avoid. You have to look in another direction if you don't want to read a word. If an action is limited to what is done intentionally, then there is a question of whether reading is an action,” Secco says.

If it is not an action in a philosophical sense, reading would fall into the same category as digestion or hiccups. Secco does not find that reasonable.

“Even though reading happens automatically, and it is easy to think that it is just something that happens to us, I want us to realise that we are actually doing something when we read. It is a skill that we have developed over a long period of time and also involves our prior knowledge,” she says.

Secco hopes that providing nuance to the concept of action can open the door to new questions and discussions within philosophy, and perhaps also within psychology and behavioural theory.

“Perhaps there are types of behaviour that we philosophers can look at with fresh eyes and assess differently. Another way forward is to think differently about the individuals performing the actions and bring philosophical ideas closer to what we really are as people who perform actions,” Secco says.

Reference:

Francesca Secco. 'Agency beyond Intentions. On the intimate connections that relate agents to their actions', PhD Dissertation, Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas, Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo, 2023. (About the dissertation)

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family