This article was produced and financed by The Fram Centre

Stricter EU rules on parabens

The EU is in the process of introducing a ban on the use of parabens in skin care products for children under six months old because of high levels of parabens in the blood of heavy users of cosmetic products.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Senior Researcher Torkjel M. Sandanger and a group of NILU researchers at the Fram Centre in Tromsø have analysed 350 blood samples from Norwegian women, and have found a very clear link between the women’s self-reported use of cosmetic products and the level of parabens in their blood.

Among heavy users, the level of parabens in the blood was actually higher than levels of all other potential environmental pollutants surveyed.

“This gives grounds for concern, because parabens are chemical substances which can disrupt the hormonal balance in the body. Studies have shown that substances of this kind which cause hormonal imbalance can have an adverse impact on fertility in both women and men. They can also lead to certain types of cancer if used over a long period of time," says Sandanger.

"There is a pressing need for more studies to be done on the effects these substances have on the population”.

Ban in Denmark

Parabens are a class of chemicals used as preservatives in a large number of cosmetic products.

Parabens have been met with increasing scepticism and concern in the past few years. Many cosmetic products also contain other chemical substances which have unknown or harmful effects.

In Denmark, this growing concern caused the government to introduce a ban on 15 March 2011 against the use of propyl- and butylparabens in cosmetic products aimed at children under three years old.

The EU’s Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) had previously taken the view that parabens did not pose a health risk, but the Danish ban triggered a new assessment which led to the SCCS in November 2011 recommending a ban on parabens in products aimed at children under six months old.

The European Commission, which is the executive organ of the EU, has since followed up the scientific recommendations and is in the process of implementing an entire EU-wide ban. The Commission also wishes to reduce the maximum permissible level of propyl- and butylparabens in all types of cosmetic products.

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority follows the EU in such cases, which means that the stricter regulation will also apply in Norway.

Parabens under pressure

NILU’s research into parabens attracted a great deal of attention in 2011. In March, Sandanger appeared on “Schrödinger’s Cat”, a TV programme devoted to science and research broadcast by Norway’s NRK1 channel, in which it emerged that the programme presenter, Hanne Kari Fossum, had twice as high levels of parabens in her blood as Erik Solheim, Norway’s Minister of the Environment and International Development.

Sandanger was also interviewed on NRK1’s health and lifestyle programme “Pulse” in November, at the same time as the Norwegian Consumer Council launched an app which can be downloaded to smart phones to check the contents of cosmetic products. The app, called “Hormone Check” warns consumers if the cosmetic in question contains potentially hormone-disruptive chemicals.

The Norwegian Cosmetics Association criticised the initiative, but the little app quickly climbed to the top of the list of the most frequently downloaded free apps.

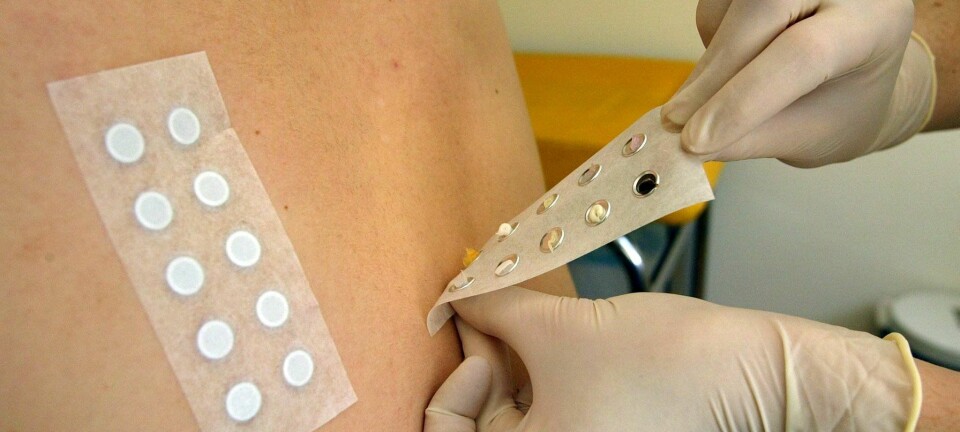

Up until now, it has been difficult to determine whether parabens are capable of causing cancer or hormonal imbalance in humans, but the researchers at NILU took a great step forward when they analysed blood samples from women taking part in the “Women and Cancer Study”. The study is headed by Professor Eiliv Lund at the University of Tromsø, who has gathered data and questionnaires from more than 70 000 Norwegian women.

NILU analysed blood samples from 350 of these women and compared them with the women’s self-reported use of skin creams and other skin care products. NILU’s research showed that parabens are demonstrably present in blood samples from randomly selected women.

“If these substances are in your blood, they’re also in your liver and in every other place in your body,” explains Sandanger.

Pregnant women should be better protected

“It’s positive that both Denmark and the EU are tightening the rules on the use of parabens, but research suggests that we should also be considering a ban with respect to pregnant women,” says Sandanger.

This is a complicated subject, but it has been shown that the exposure to parabens of a foetus in the womb has more serious consequences than exposure after birth. The EU’s Scientific Committee has nevertheless taken the view that there is no reason to introduce such a ban until it has more documentary evidence.

“We humans are exposed to thousands of chemicals every single day, and the basic idea should be that we don’t need even more chemicals in our bodies. Today, researchers must prove that there is a probability that a substance is dangerous before the authorities can ban it, but it would be better to apply the precautionary principle. We know little about how each substance affects the body and the environment, but we know even less about the cocktail effect, that is, the combined effect of multiple chemicals interacting with one another,” warns Sandanger.

“In this area people are of course quite free to make their own choices without waiting for stricter legislation. The Consumer Council’s app and other aids, such as the website of the Norwegian environmental organisation Grønn hverdag [Every Day Green], have made it quite easy for most of us to avoid products containing parabens,” Sandanger adds.