THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Norwegian authorities have earned the public's trust through openness about their COVID-19 strategy

Communications researcher Øyvind Ihlen finds it more than likely that the Norwegian government's communication concerning COVID-19 may have saved lives.

When a pandemic occurs, public confidence is at stake: both trust between people and the people's trust in the authorities, according to Øyvind Ihlen, media researcher at the University of Oslo.

Good communication becomes paramount.

In 2019, Ihlen and his colleagues had started a research project on risk communication in pandemic situations. Could the researchers help the government communicate well, should such a situation arise? COVID-19 made the project highly relevant.

For the time being, Ihlen finds little to criticise the Norwegian government for.

“Much of what they do is right,” he says.

The research is ongoing, and Ihlen and his colleagues will eventually be able to identify clear points of improvement. But in terms of communicating candidly about COVID-19, he thinks the Norwegian authorities have done very well.

Openness is not merely the opposite of concealing facts

Being open and honest is an established ideal of democratic governance. This has also characterised communication relating to the pandemic in Norway. In 2020, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health was awarded awards for openness from both the Norwegian Press Association and the Norwegian Communication Association.

Ihlen and his colleagues wanted to study what openness entails. They also wanted to study openness in Norway and the other Scandinavian countries.

“We often have a notion that openness means we don't conceal anything, such as revealing the data that we have. But this understanding is incomplete,” Ihlen says.

He points out that if one merely releases data, it might result in confusion and unrest. Openness is linked with

- people understanding the data

- responsible communication, for example that objections are presented and criticism is accepted

- dialogue with your surroundings

In the ongoing study, researchers are discussing how these three points have been maintained by health authorities in Scandinavia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research is based on interviews with the health authorities’ communication personnel, observational data, analyses of television appearances and focus group interviews.

More caution in Sweden

The researchers have noticed that there are differences between the kinds of openness shown in Norway, Sweden and Denmark during the pandemic. Whereas the Norwegian authorities have been praised, Swedish authorities have been criticised for their lack of openness.

At a press conference in March 2020, the Swedish state appointed epidemiologist Anders Tegnell was asked about why the authorities couldn’t be open and share numbers like other countries do.

“He replied that ‘the people who need numbers will get them’. This mirrors a slightly different view of openness in the Swedish government apparatus than that of Norway,” Ihlen says.

The research conducted by Ihlen and his colleagues shows that the Swedish government, at an early stage, before the pandemic came to the country, was anxious that they might create fear. This may have made them cautious about going public with the disease scenarios, Ihlen believes.

Different spokespersons

The researchers have seen other differences in pandemic-related communication in the Scandinavian countries. For example, different government agencies have spoken officially in different countries.

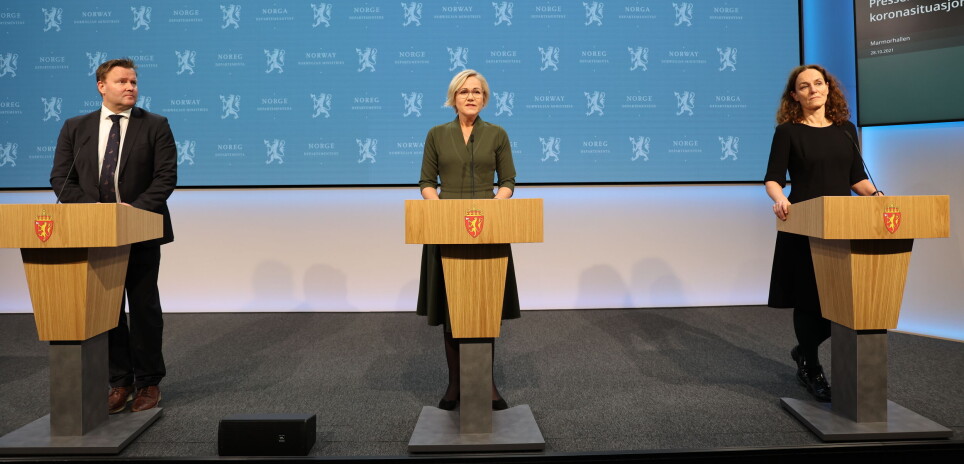

In Sweden, the prime minister stepped aside, and the health authorities handled communication. Thus, experts were given greater responsibility. In Denmark, the prime minister took charge, while the health authorities were assigned a role on the sidelines. In Norway, both professionals and politicians made public announcements, but the politicians had the final say.

In some cases, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health gave advice based on their expertise, but the politicians chose not to follow it. This was the case, for example, in the decision to close schools and kindergartens in March 2020.

“In these cases, it was important for the Norwegian Institute of Public Health to communicate that they had given different advice. They also stressed that this was all right, that it was the politicians who should be responsible for the handling of the pandemic.”

Open about uncertainty

In 2021, the Norwegian Corona Commission praised the Norwegian authorities for being open about uncertainties and differences of opinion.

“In the specialist literature, there are differences of opinion about such communication. It may be risky, but it doesn't necessarily have negative effects on people's confidence in those informing the public. Instead it may have the complete opposite effect, namely that it boosts confidence. At least we see that in the case of Norway,” Ihlen says.

In Sweden and Denmark as well, spokespersons were open about uncertainty and differences of opinion. But while this primarily came to light through interviews, Norwegian spokespersons frequently appeared on discussion panels. They were ‘extremely available’ to the media, according to Ihlen.

Trust makes countries better equipped

In all three Scandinavian countries, the authorities enjoyed a high level of trust from the people when the pandemic started. According to Ihlen, this made these countries better equipped to deal with a pandemic than many others.

However, he notes that there are at least two other factors that determine trust in the authorities during a pandemic: how they communicate, and the experience that the pandemic is being satisfactorily handled.

In Norway, according to the Norwegian Directorate of Health, about 80 per cent of the people say they are highly confident or very highly confident that the health authorities have handled the pandemic in a satisfactory manner. This percentage has remained relatively stable during the pandemic, with the exception of a dip of around 20 per cent in February 2020, before the introduction of strict measures.

In Denmark, too, confidence has been high, but more marked by political scandals and fluctuations. In Sweden, confidence has fallen quite sharply since March 2020 but still remains high when compared with countries such as the UK, France and Switzerland.

May have saved lives

All the Scandinavian countries have emphasised openness in their pandemic communication, especially in terms of releasing numbers and information, according to Ihlen. Nevertheless, interviews with Swedish communication spokespersons suggest that the attititude toward the openness strategy varies more among Swedish institutions.

It seems that Sweden has been less open in pandemic communication than Denmark, which in turn has had less open communication than Norway.

Can one conclude that the Norwegian authorities have handled the pandemic better than the government officials in neighbouring countries?

“The numbers speak for themselves. There have been fewer deaths per million inhabitants in Norway than in neighbouring countries. This makes us think that Norway has done a good job,” Ihlen says.

He stresses that the numbers are not related exclusively to the authorities’ communications efforts. For example, Norway is sparsely populated, and this may have slowed the spread of infection.

“But people have been cooperative about accepting the advice and recommendations of the authorities, too. Trust plays a significant role in that respect, as well. So it is possible that communication may have saved lives,” he concludes.

References:

Truls Strand Offerdal et.al.: Public Ethos in the Pandemic Rhetorical Situation: Strategies for Building Trust in Authorities' Risk Communication. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research, 2021.

Jens Elmelund Kjeldsen et.al.: Expert ethos and the strength of networks: negotiations of credibility in mediated debate on COVID-19. Health Promotion International, 2021.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family