THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Feminism asserts itself in Chinese science fiction

Science fiction is popular at the same time as a new wave of feminism hits China. This leads to more attention for female authors of the genre.

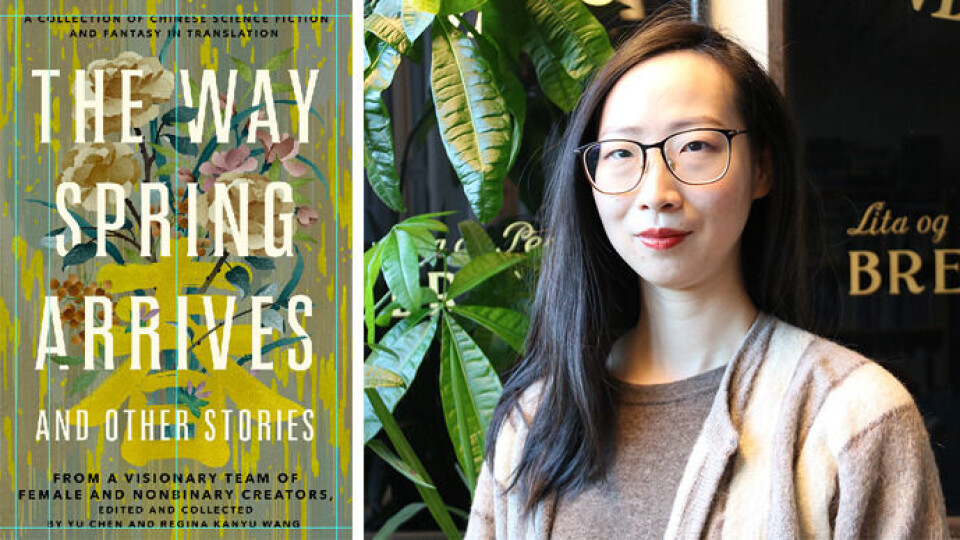

“Originally, science fiction was a hobby for a minority group. Today there are more companies willing to invest in science fiction, and the government is establishing industrial science fiction parks for tourism purposes in China,” Regina Wang says.

Wang is a Doctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, and is doing research on the science fiction genre.

Lately, Chinese science fiction has been getting a lot of attention in China, but also internationally.

Fan, writer and researcher

Wang works within the research project CoFutures: Pathways to Possible Presents, where they look at global science fiction and the non-anglophone tradition, researching science fiction from Latin- America, Africa, India, Arabic speaking countries, and more.

Wang is researching the genre in Chinese. Her interest in science fiction started a long time before it became popular in China. She started out as a fan, then began writing stories herself.

As a researcher, she looks at science fiction texts, movies, TV series and arts.

She gives the book The Three-Body Problem written by Liu Cixin, and Hao Jingfang's novelette Folding Bejing much of the credit for popularising Chinese science fiction. Both stories have won the Hugo Award, in 2015 and 2016 respectively.

This international award is given annually by the World Science Fiction Society for best science fiction work.

Market interest creates more topics to explore

The most popular science fiction author in China, Liu Cixin, writes in the same style as the classic writers within the genre, such as Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert A. Heinlein.

“Liu’s huge success brings attention and market interests to science fiction in China, and thus opens doors to other styles,” Wang explains.

The popularity makes it easier for stories that differ from the classics within the genre to get published.

“A larger market and more platforms on which to publish stories now give science fiction writers the opportunity to explore a larger variety of topics,” she says.

In the past few years, she has seen that science fiction authors are also writing about indigenous people and people of different ethnicities.

“They incorporate more forms of cultural heritage, using mythology stories, folktales and mindsets, in imagining the future,” Wang says.

The popularity of science fiction makes it possible for more people to write, and it also attracts those interested in feminism.

Feminism in science fiction?

While science fiction has gained in popularity, the Me Too movement has contributed to a greater awareness of feminism in Wang's home country.

“When the popularity of science fiction and feminism coincide, like in recent years, it becomes a phenomenon that more people are interested in and talking about,” she says.

The last time feminism was a topic of discussion in China was in the mid 1990s, when the UN's Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing.

“At that time the commercialisation of feminism in China stopped women writers from talking about it. You didn’t want to be a beautiful female writer, but a good writer,” Wang explains.

Today, more women are joining the discussion, and because of the Internet, more people are aware of ongoing debates, she thinks.

In those discussions, female science fiction authors receive more attention. Wang has looked more closely at the topics in the genre.

Common topics

“Some of the stories reflect the author’s concerns about reproduction and the female body,” Wang says.

Examples can be found in online novels about reproduction in the future.

“There are all kinds of imaginative stories about women that are required to bear children, like in The Handsmaid’s Tale. But you also have stories about men in matriarchal systems,” she says. “They don’t write about radical feminism or about an oppressive patriarchy, but try to weave in feminist themes in more subtle ways."

She adds: “One way to explore how feminism is expressed in their stories is to look at how they incorporate the concept of Yin, which represents feminine and softer values, in contrast to the masculine Yang."

Moreover, it is clear that female writers in China think about the fact that the protagonist is most often a man.

“In the past we didn’t challenge this idea. The dominant tradition being masculine, it is natural to read science fiction stories with a male as the protagonist. Nowadays, there are more women writers who reflect on these things. They write female astronauts or scientists into their stories about the future. That way, we get more feminist thinking and input in science fiction,” Wang explains.

She believes they still have a long way to go within the genre, and compares China with Korea.

“Korean writers are using the feminist movement more actively in science fiction in order to explore feminist ideas,” she says.

Explores the unknown in various ways

Feminism is not the only topic influencing Chinese science fiction. In the stories, you also find subjects such as environmental issues and the pandemic.

In 2020, Wang wrote the story A Cyber-Cuscuta Manifesto for The Center of Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University, about parasitic beings in the digital world that feed on people's data. Despite the fact that they sustain themselves by imitating data, they do no harm, but on the contrary tidy up our digital world.

“The story proposes that we should coexist with things we do not know that much about yet. Not only in the physical world, but also in the digital one,” she says.

One of Wang's favourite science fiction stories is The Martian Architect, written by Xia Jia, one of China's most famous female science fiction authors. There is a story inside the story about a group of people who live on Mars and are faced with a difficult choice when a spaceship arrives. Everyone aboard has died from a virus, except for a small child.

“So they need to decide: Should they let the child on to the planet and risk being infected themselves, or should they reject it and let the child die alone in space,” she says.

Instead of choosing one of those two alternatives, the protagonist finds a third option. She decides to go live on the spaceship with the child and create a new society along with others who gradually join them.

It is precisely this third possibility that makes the science fiction genre so fascinating, Wang believes.

“Science fiction is about pushing boundaries and suggesting new solutions. I think that is a key feature of the genre,” she says.

Science fiction can also contribute a global perspective on the climate challenges we are facing.

“From an individual perspective global changes are happening at a distance and on a scale that is difficult to relate to our daily life. But in science fiction, you can change your perspective and look at our whole species, planet and universe. So it can provide you with a different way of thinking, and hopefully, it can help people think new thoughts about the challenges we are facing,” Wang says.

A chosen metaverse and the near future

The most popular topics in Chinese science fiction is still artifical intelligence and the metaverse. But the stories have changed.

“In the past, the stories were about people escaping into a virtual world in order to avoid an uninhabitable planet. But in recent years, stories are about people who seek out the virtual world voluntarily, embracing all the alternatives, stimulation and entertainment there because they want to,” Wang says.

She also finds that people are more interested in reading about the near future, from 50 to 100 years forward in time.

“They take advantage of certain tendencies in technology and in the society and try to relate these tendencies to what might happen in the near future. Because it might happen soon, it makes people feel more connected to the story,” she says.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family

-

How international standards are transforming the world

-

A researcher has listened to 480 versions of Hitler's favourite music. This is what he found

-

Researcher: "AI weakens our judgement"

-

New, worrying trend among incels, according to researcher

-

Ship’s logs have shaped our understanding of the sea