THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY Fridtjof Nansen Institute - READ MORE

Russia pushes for a fossil economy. Can China stop them?

“It's China that has the upper hand,” says researcher.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Western sanctions quickly followed.

Europe cut imports of Russian oil and coal dramatically. Russia had to turn to new markets.

China became the lifeline – at least on paper.

“Russia has become increasingly dependent on China, especially as a buyer of oil and coal,” explains Anna Korppoo, researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI).

She studies Russian climate policy and analyses the developments in energy trade between Russia and China.

“For Russia, China is now the most important market. But for China, Russia is only one of several options,” says Korppoo.

Selling oil and coal to China at a loss

After the EU embargo on Russian coal in 2022, Russia tried to adapt quickly.

According to Korppoo, exports to China became essential to keep the sector alive.

But today, the picture looks grim:

“Two-thirds of Russian coal companies are now running at a loss. Transport costs, weakened competitiveness, and falling coal prices make it difficult to earn money,” says Korppoo.

What worries Russian policymakers the most, she adds, is the lack of alternatives.

“Russia has no plan B. But China has many,” she says.

How green is China’s transition?

At the same time, China has built up the world’s largest renewable energy sector. By 2024, the renewable industry accounted for about ten per cent of China’s GDP.

Still, China relies heavily on coal for energy security. Around 53 per cent of the Chinese energy mix still comes from coal, according to Gørild Heggelund, researcher at FNI.

She points out that China is now preparing new climate measures in its upcoming five-year plan. This will apply from 2026 to 2030.

And for the first time, all greenhouse gases, not just CO₂, will be included in targets towards 2035.

This was announced by President Xi Jinping at a virtual meeting of world leaders organised by the UN and Brazil earlier this year.

This is a positive signal, but it comes with challenges.

“Coal is still regarded as the most secure energy source in China,” says Heggelund.

Although coal consumption has declined by about one per cent annually in recent years, China’s ambitions are high and difficult to achieve. Dependence on coal remains a major obstacle.

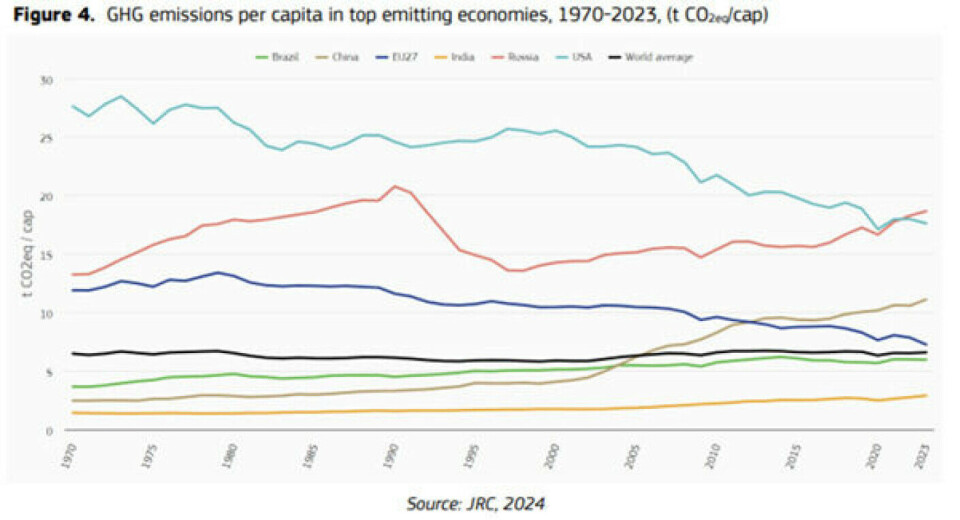

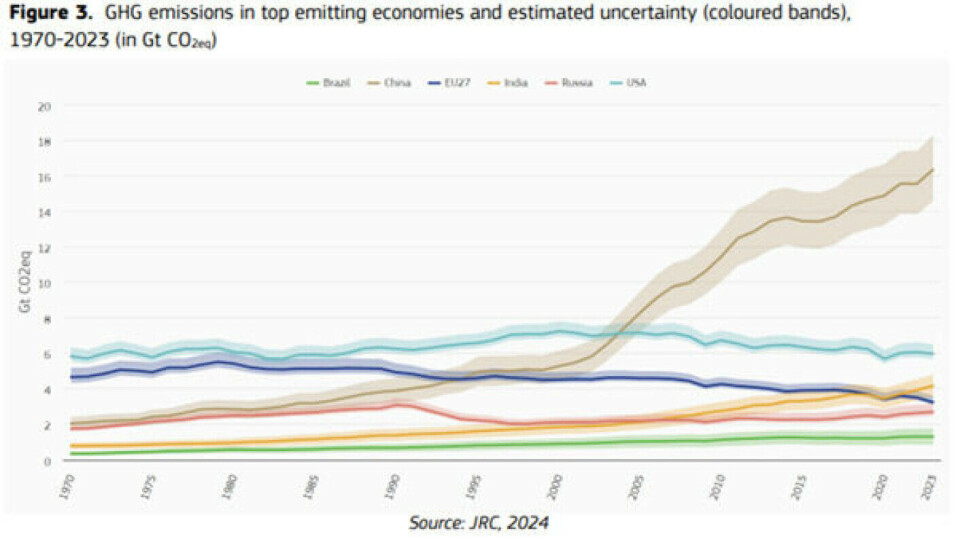

“China is the world’s largest emitter, accounting for over 30 per cent of global CO₂ emissions. This gives the country a special responsibility to cut emissions,” she says.

Is China becoming a climate leader?

“It's easy to get the impression that China is becoming a climate leader, but the country is still deeply dependent on coal. Growth in renewables and the establishment of a carbon market have not yet resulted in real emission reductions,” says Korppoo.

Researcher Iselin Stensdal agrees. She studies China's renewable industry at FNI.

At the same time, China has become a dominant player in the global export of renewable technology, especially to Europe and the global south.

“China’s green shift is not only about the environment. It's also about domestic economic growth and geopolitics,” she says.

A “non-Western climate coalition”?

From the Russian side, there has been talk of building an alternative climate coalition together with China and other countries critical of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

But according to Anna Korppoo, there is little evidence that China wants to integrate with Russia on climate policy.

There is some dialogue in forums such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. But for China, linking its carbon market to Russia would dilute and weaken its own efforts, she explains.

“China’s climate measures are real, while Russia’s climate policy is largely rhetorical,” she says.

“China seeks influence, but not necessarily partners like Russia,” adds Stensdal.

What does this mean for Europe?

The energy shift between Russia and China does not take place in a vacuum.

For Europe, the key is to understand the new rules of the game.

“We expect stricter climate goals, more use of renewables, and an expansion of the national carbon market,” says Heggelund.

China’s green industrial policy is therefore likely to have effects far beyond its own borders.

References:

Korppoo, A & Allisson, A. Russia’s Non-Western Climate Coalition: Genuine Consensus or Just Hot Air? Climate Strategies Report, 2025.

Stensdal, I. & Heggelund, G. (Eds.) 'China-Russia Relations in the Arctic: Friends in the Cold?' Palgrave Macmillan, 2024. ISBN: 978-3-031-63087-3 (Summary)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

This content is paid for and presented by Fridtjof Nansen Institute

This content is created by Fridtjof Nansen Institute's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Fridtjof Nansen Institute is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more.

More content from Fridtjof Nansen Institute:

-

“It's been a long time since we've seen so many positive developments in such a short period. We may indeed be entering a turning point for nature”

-

Russia could lose its big chance in the global gas market

-

What does China aim to gain in the Arctic?

-

Where do the metals in your electric car come from?

-

Power struggle in the Arctic Council: Greenland demands a leading role

-

War in the Arctic? Researchers debunk three myths about the High North