An article from Norwegian School of Economics (NHH)

Economists call Norway's climate policy hypocritical

More and more economists are critical of Norway's prevailing climate policy and believe that the country should stop exploiting North Sea oil.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The discovery of oil on the Norwegian Continental Shelf in 1969 revolutionized life in Norway. Over more than 40 years, petroleum production on the shelf has created considerable wealth for the country, adding more than NOK 9000 billion to the country’s GDP, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

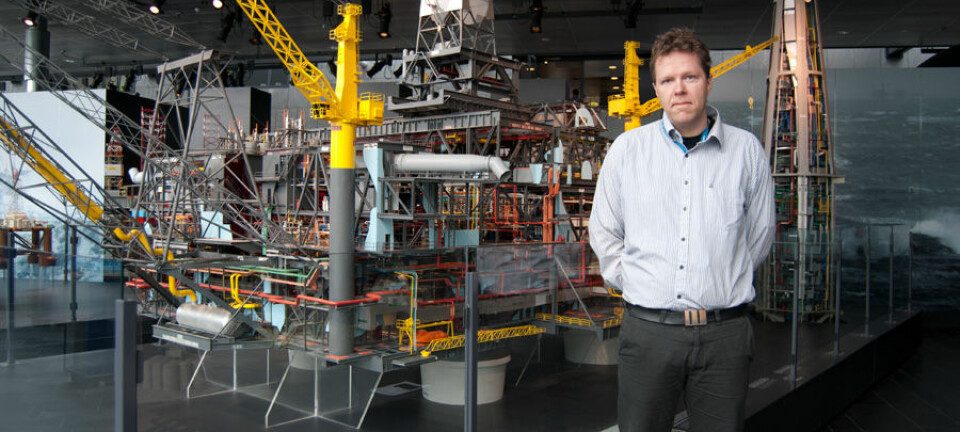

At the same time, the Norwegian government has taken a strong stance on environmental issues that affect climate change. But Professor Gunnar Eskeland, an economist and professor in the Department of Finance and Management Science at the Norwegian School of Economics, says Norway's reliance on oil wealth while pushing other countries to take measures to protect the climate is hypocritical.

"This is a very controversial view, because Norway has become so dependent on its oil revenues," Eskeland says.

Cheap carbon credits no solution

"Let's say that we're carbon neutral in 2030." says Eskeland. "And that the rest of the world is wondering how we managed it. If the answer is that we planted a lot of trees in Guatemala, the reaction will be: 'You're so stinking rich!' How impressive is that? Prime Minister Stoltenberg may be right when he says that these are the cheapest emission reductions, but what we are doing in this field is perhaps mostly of symbolic value."

Eskeland says that even though many economists would argue that the smartest way to reduce emissions is to do it in the cheapest way possible, he thinks Norway shouldn't just buy its greenhouse gas reductions abroad.

Buying indulgences

The climate economist draws a comparison with the Reformation and Martin Luther.

"It is hypocritical if all we do is buying indulgences. It's not OK to commit adultery just because you're rich or friends with the Pope. That's just not acceptable, and it is certainly not earning you a position as a leader in society. Luther probably believed that rich people should be direct role models," he said.

"We can achieve cheap reductions by buying them abroad. But it's just a drop in the ocean," agrees Linda Nøstbakken, who holds a PhD from the Norwegian School of Economics.

"If the world were to reduce the oil recovery rate, that would have an immediate effect on the world's carbon emissions. To reduce the probability of disastrous climate change, much of the hydrocarbons must be left in the ground," she said.

Oil sands in Canada

Nøstbakken is also an assistant professor at the Alberta School of Business in Canada. She has lived for a number of years in Alberta, which is at the heart of the world's oil sands debate, and says she is frustrated by Norway's attitude to the oil sands industry.

"Norway can't go around the world telling Canada to shut down its oil sands industry when we are pumping up oil and recovering gas ourselves," she says.

Nøstbakken disapproves of what she describes as a double standard.

"We Norwegians go around the world telling other nations what to do. But we are doing very little ourselves. The Minister of the Environment recently presented a white paper on Norway's climate efforts. He was asked how these efforts would affect people. We were told that they would benefit us. The measures largely involve reshuffling funds that the state already has. If that is the Norwegian way of being more environmentally friendly, I have a problem with that," Nøstbakken says.

"What are we doing in Norway? Our oil sector is subject to enormous taxes, but this is actually money that comes straight from our own oil fund. That is self-defeating. I am not sure that others take us very seriously in this context," she adds.

Selling oil as fast as possible

Eskeland says Norway would benefit from a debate that challenges the country's distinction between oil policy and climate policy.

"Until now, Norway has managed to shield the development of the offshore sector from its big promises about climate policy, but we might not be able to continue this line in future."

He says that talk about reducing carbon emissions is hypocritical unless Norway explains how its oil production policy is affected, if at all.

"Those who own oil or gas in this century risk losing a lot of their wealth if the world stops using fossil fuels before we run out of them. That means that it is becoming more urgent for everyone – including us - to sell our oil. It seems hypocritical for Norway to tell the rest of the world to reduce emissions while we ourselves are selling our oil as fast as we can," he says.

Dependent on oil revenues

Professor Bård Harstad, an economist from the University of Oslo, also argues that we should do something about the supply side rather than the demand side if climate measures are to be effective. The world would then actually have to put aside fossil reserves, says Harstad.

"That is a controversial proposal that changes the debate," says Eskeland, "because what is happening in Norway is influenced by our dependence on oil revenues."

"But we are seen as a successful country in terms of how we manage our oil assets," says Nøstbakken.

An oil nation to the last drop?

"Others believe that we should save the oil because it will be more valuable in future. But climate policy means that some fossil fuels shall be left in the ground, unexploited. Perhaps some of ours? So there are many different arguments here," Eskeland says.

"Perhaps, in the future, we can use the oil with hardly any emissions," Nøstbakken counters. "We cannot know that at present."

Energy-intensive residual oil

The biggest Norwegian climate project is what is called the "moon landing", a test centre for carbon capture and storage that opened in May in Mongstad. The carbon capture plant should be fully operational from 2020. By that time, the cost of the plant will have reached almost NOK 25 billion.

At the same time, many Norwegian oil fields are nearing the end of their lifetime, and extracting what is left is far more energy-intensive. The emissions from oil and gas activities will therefore remain at about the same level until 2020, even though production will gradually decrease.

A bigger percentage of production will consist of gas, which requires a great deal of energy whether it is transported in pipelines or frozen for shipping.

Carbon capture is the only solution that can justify continued extraction and use of fossil fuel, Eskeland believes.

Journey of discovery

"It should come as no surprise that big oil nations and coal companies are investing a few billion in such projects (like Mongstad), since a solution of this kind could prove very valuable to them. Norway is one of very few natural candidates for a project like this," he says.

If the experts are right about future climate change, the world will need carbon capture, or, at the very least, we need to be absolutely sure that it does not work, Eskeland believes. He says the carbon capture journey of discovery is worth a great deal to the world.

Article updated May 8, 2013