THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Recommends keyhole surgery for cancer of the liver

Those who had tumours removed from their livers with keyhole surgery had fewer complications, a better quality of life and similar long-term oncologic outcomes, a new PhD thesis shows.

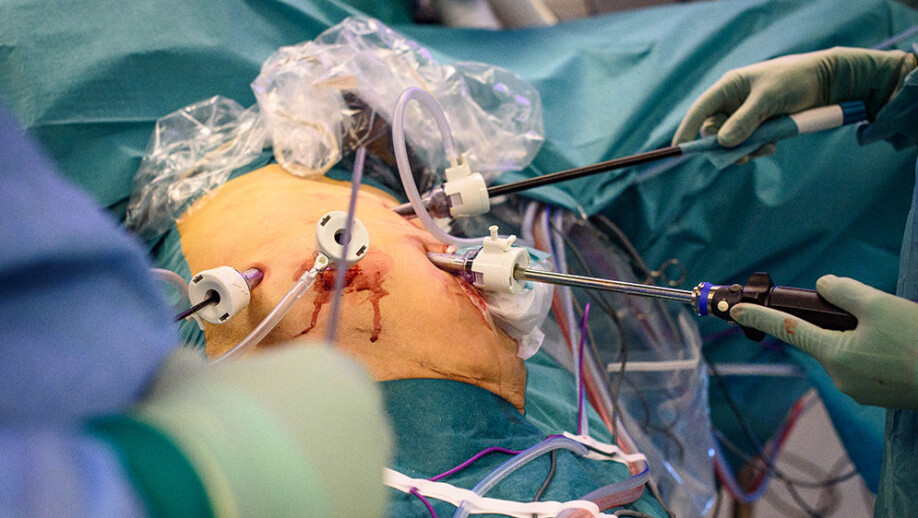

In many patients with colon and rectal cancer, cancer spreads to the liver. Several patients are now being operated on using a technique called keyhole or laparoscopic surgery, where the surgeon merely attempts to remove tumours with sufficient surrounding health tissue. This type of surgery is called a laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing liver resection.

But do these kinds of keyhole surgeries work just as well as operations where the patient is opened up? Does the patient live just as long afterwards? What about complications and quality of life? This is what Davit L. Aghayan wanted to find out when he started his PhD at the University of Oslo.

“On average, those who underwent keyhole surgery for tumours in their liver, only needed to stay two days in hospital afterwards. In addition, they experienced fewer complications and reported better subsequent quality of life. Patients who underwent open surgery usually had with roughly a 30-centimetre incision in their abdominal wall, and, on average, had to stay in the hospital for four days,” Aghayan says.

Similar survival

The findings were revealed in a randomised trial of almost 300 patients at Rikshospitalet. Aghayan stressed that, if the patients would not live just as long as after traditional open surgery, these findings would not be worth as much.

“The median follow-up of these patients was six years. Just as many survived with both forms of surery,” he says.

Neither was there any difference in whether the patients developed new tumours.

Consequently, Aghayan believes that more patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases should be operated on through keyholes with the parenchyma-sparing strategy, although this surgical procedure cannot be applied on absolutely everyone.

Should operate many people with liver tumours to gain experience

Only in the last 20-30 years have surgeons resorted more to using laparoscopy . During keyhole surgery, surgeons make small holes through which they insert a camera and the instruments they are going to use during the procedure. The surgeons then look at a screen while they do the operation .

Keyhole surgery has been shown to have many advantages over traditional open surgery in different types of cancer surgery, such as colorectal, gastric and oesophageal cancer. However, in some studies of patients with cancer of the cervix and the pancreas, it was reported poorer outcomes of keyhole surgery than traditional open surgery. Aghayan thinks that one factor that may have played an essential part here is how much experience surgeons and the surgical team have with these types of operations.

“In Norway, where we have centralized surgery of liver and pancreas cancer. Liver operations are only performed in the university hospitals and these amount to five hospitals. The Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet takes care of patients from the entire South-East Regional Health Authority, which is about 60% of the Norwegian population. In comparison, in Germany such operations are carried out in over 1,100 different hospitals,” he says.

Aghayan has had section leader and Professor Bjørn Edwin at the University of Oslo as a supervisor. Edwin was the first to use keyholes in Norway on these types of cancer patients in 1998.

Until the CoMet trial, there was limited documentation with low evidence level about the patient group being treated with this method of surgery. Recently, Aghayan's successful disputation resulted in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Oslo passing thesis number 5000.

Reference:

Davit L. Aghayan: Laparoscopic parenchyma-sparing surgery in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Doctoral dissertation at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, UiO, 2020.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"