THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

New study reveals how your brain organises experiences in time

Researchers in Norway have discovered a pattern of activity in the brain that serves as a template for building sequential experiences.

“I believe we have found one of the brain’s prototypes for building sequences,”

says Professor Edvard Moser. He is part of the research team at NTNU's Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience.

He describes the activity pattern as “a fundamental algorithm that is intrinsic to the brain and independent of experience.”.

The breakthrough discovery was published in Nature December 20, 2023.

The ability to organise elements into sequences is a fundamental biological function essential for our survival. Without it, we would not be able to communicate, keep track of time, find our way, or even remember what we are in the process of doing.

The world would cease to present itself to us in meaningful experiences, as every event would be fragmented into an erratic series of random happenings.

The NTNU researchers' discovery of a rigid sequence pattern in the brain provides new insights into how we organise experiences into a temporal order.

The sequential nature of memory

Have you ever heard memories described as snapshots? That is not a very faithful description, according to Edvard Moser.

“It's more helpful to think of memories as videos,” he says.

“All your experiences in the world extend over time. One thing happens, then another thing, then a third,” Professor May-Britt Moser says.

Your brain has the remarkable ability to mentally capture and organise selected events into the chronological order in which they occurred, and to link them together as meaningful experiences.

This sequence building activity takes place on the timescale in which you interact in the situation. When you recall this memory, the process of reliving the sequence of events in your mind also takes time.

“How is the brain able to generate and store all these unique and lengthy sequences of information on the fly? There has to exist a foundational mechanism for sequence formation there,” Edvard Moser says.

“There is a mismatch in neuroscience between the timescales at which brain activity is typically studied, in the millisecond regime, and the timescales at which many of our most important brain functions occur, in the tens of seconds to several minutes range,” Soledad Gonzalo Cogno says. He is a Kavli research group leader and first author of the paper.

The experiment

The team set out to identify this fundamental mechanism for sequence formation, which occurs on very slow timescales, like most of our brain functions do.

To uncover how neurons coordinate at the slow timescales, the researchers focused on the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC). The MEC is an area of the brain that supports brain functions that depend on sequence formation, such as navigation and episodic memory, which unfold very slowly in time.

The sheer volume of information about the outside world being processed in the brain at any one time posed a challenge to the pursuit. Any baseline signal from structured and recurrent neural algorithms would risk drowning in the 'noise' of incoming experience.

To get around this, the researchers created an experimental environment that was almost devoid of sensory inputs. They let a mouse run in complete darkness, with no task to complete and no reward to earn. The mouse could run or rest as it pleased, for as long as the session lasted.

At the same time, the researchers recorded what was happening in the entorhinal cortex of the mouse’s brain while its orchestra of nerve cells remained in this standby position.

A fundamental brain mechanism for sorting information into sequences

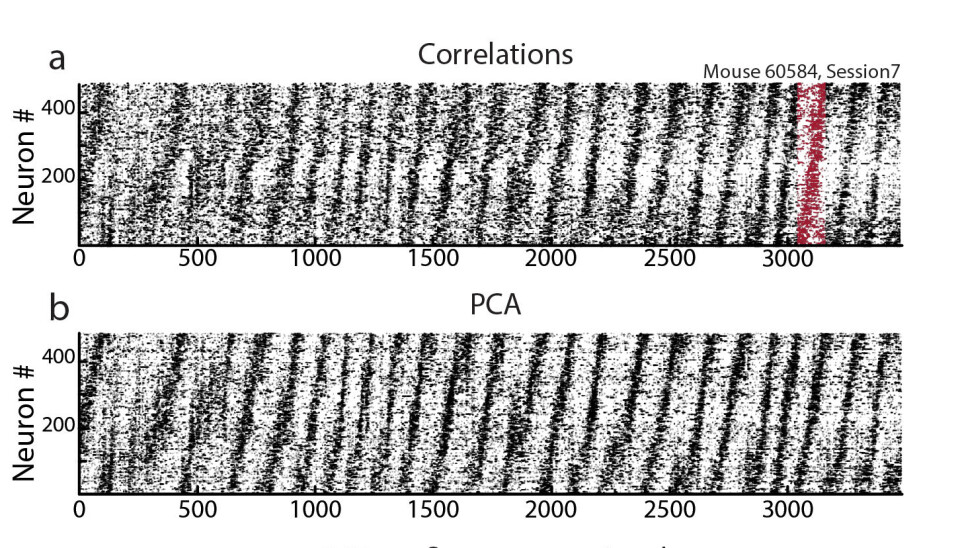

“This is what we found,” Cogno says, pointing to a zebra-striped figure in front of her.

The pattern is made up of thousands of dots clustered together. Each dot is a neural signal. We can see that the neural activity moves through all the cells from bottom to top along the Y-axis as time progresses along the X-axis.

The clustering tells us that the activity is coordinated as waves running through the network, like rhythms in a symphony. The sequences are ultra-slow, meaning that it takes two minutes for the wave to travel through the neural network, before the whole process repeats again, sometimes for as long as the duration of the test session, over periods of up to an hour.

The figure shows several hundred mouse entorhinal cortex neurons oscillating at ultra-slow frequencies, spanning time windows ranging from tens of seconds to several minutes.

The dynamic that excited the researchers even more is that as each cell oscillates, the cells also organise themselves into sequences, with cell A firing before cell B, cell B firing before cell C, and so on, until they have completed a full loop and return to cell A, where the cycle repeats.

This highly structured activity overlaps with the timescale of events that we encode into our memories and provides the perfect template for building the sequential structure that forms the basis of episodic memories.

These waves of coordinated activity did not travel in a straight line from one end of the brain tissue to the other. Instead, the waves travel along the thin synaptic connections between cells that talk to each other in the network.

Cells can talk to other cells far away as well as their nearest neighbours. The anatomical tangle makes it difficult to see coordinated activity with the naked eye without first having located the cells from the raster plot.

The video below illustrates this:

Zebra-stripes, spiral, and ring

The zebra-striped raster plot shows the slow waves of activity through the whole network over a period of time.

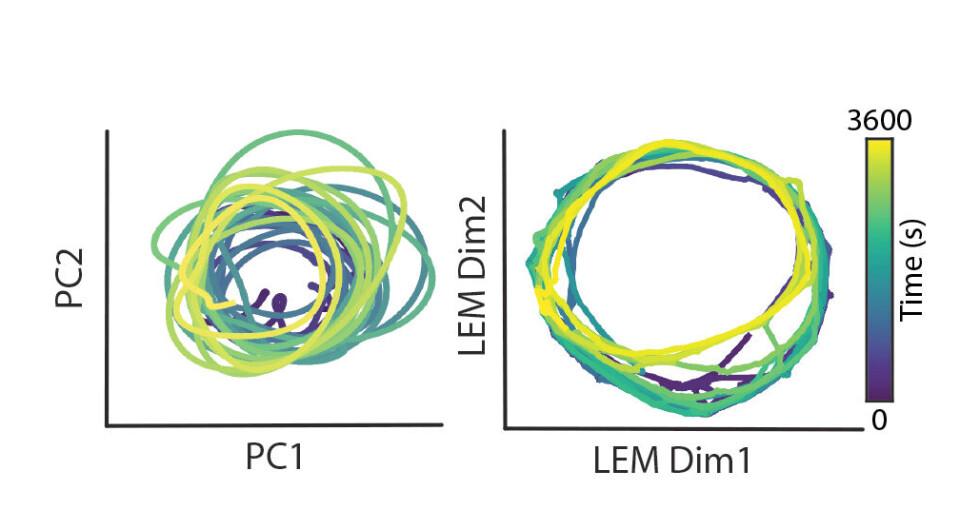

“If you fold the raster plot into a tube, so that the top and the bottom of the figure overlap, you will see that the diagonal stripes connect to form a coherent spiral. The spiral represents the network activity over time,” May-Britt Moser explains.

If you rotate the spiral by 90 degrees, you will see a ring. All the cells in the network have their set time to fire, distributed across the surface of this ring. The signal travels through the entire ring structure before returning to the same cell.

“This ring is a signature for coordination patterns in the form of repetitive sequences, which is what we found in the MEC. Other brain areas have different coordination patterns,” Cogno says.

Your brain may already be equipped with this ring before you experience anything in this world. It is acquired through evolution and may be specified in our genes.

“What excites me most about this discovery is the prospect that these sequences may open up for new ways of understanding the brain. The discoveries that follow may challenge the way we think about coordination throughout the brain. Cells that are so different still seem to be coordinated and work together on different timescales,” Cogno says.

Reference:

Cogno et al. Minute-scale oscillatory sequences in medial entorhinal cortex, Nature, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06864-1

More content from NTNU:

-

This determines whether your income level rises or falls

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?