THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Can 19th century botany inspire the climate struggle of today?

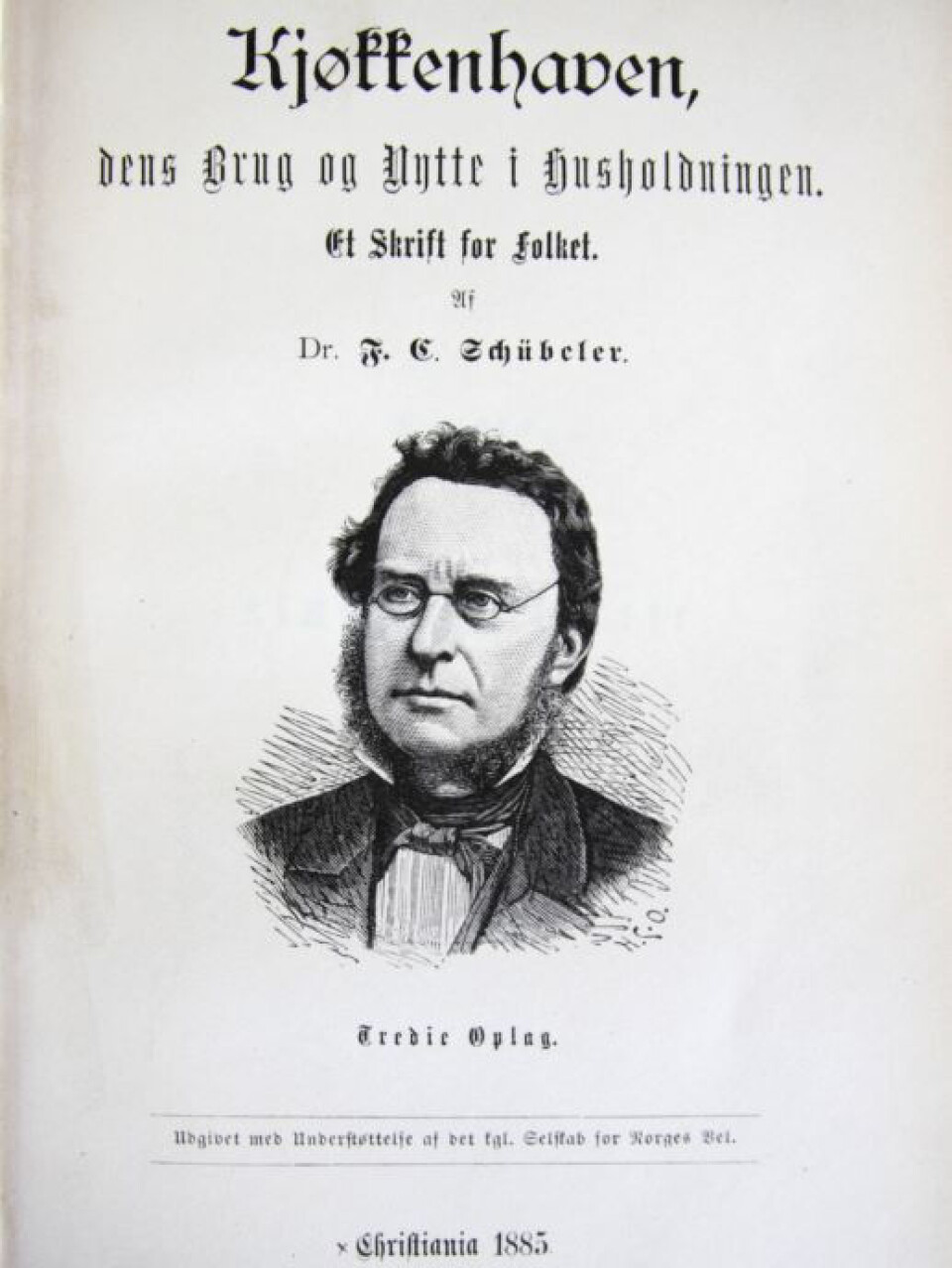

Frederik Schübeler passionately shared his knowledge about nature and taught people how to cultivate their own produce.

Climate change is one of the major societal challenges of our time. This has brought forgotten educators back into focus.

Solveig Siem, a PhD candidate in Cultural History and Museology, has brought Frederik Schübeler, known as the father of Norwegian horticulture, back into the spotlight.

In the project Afterlives of Natural History, she and other researchers from the University of Oslo are studying methods and practices from the history of natural sciences.

The project includes researchers from the Natural History Museum, the Museum of Cultural History, the Norwegian Folklore Collection, and the National Library of Norway.

Dissemination of knowledge relating to nature

Schübeler’s gateway to the natural sciences was, as with his contemporaries, medicine studies in the 1830s. He later became a well-known professor of botany.

Siem is investigating Schübeler’s work at the Botanical Garden in Oslo.

“Schübeler is interesting to the project as he was not only interested in botany as a science, but also collected information about the geography and histories of plants. He even cited the Norse Sagas,” she says.

She explains that he felt that these pre-scientific works had value. So much value in fact, that he felt they deserved to be mentioned and discussed alongside the new cutting edge knowledge he was producing about plants in Norway.

Schübeler was part of the 19th century network of naturalists, in an era when new disciplines were emerging and there was more specialisation in subjects.

His expertise was in botany, but unlike others he was not concerned with science for the sake of science, instead being more concerned with the practical benefits for the general population.

“I am interested in Schübeler not only as a botanist, but as a museum pioneer. I want to look at how he used the museum and the garden to bring knowledge from universities to the population at large,” Siem says.

The botanist who taught people how to use their gardens

Schübeler frequently published scientific and historical knowledge of plants through journals, books and newspapers.

He also received international recognition for the work he did together with priests and priests’ wives in a network of 80 research stations dotted across Norway.

The collaboration with priests and their wives meant that Schübeler was able to collect knowledge of how various species of plants grew in different parts of Norway.

Siem has looked through archives and digitised newspapers, and has also examined letters between Schübeler and the amateurs at the research stations.

“The collaboration with research stations benefited both parties. While Schübeler was able to collect knowledge of plants, the priests and their wives at the research stations learned how to cultivate plants and share their knowledge with people in the local community,” she explains.

Schübeler was invested in collecting knowledge about acclimatisation and contributed to the development of a machine that would pulverise fish waste into fertiliser.

However, not all of Schübeler’s experiments were successful. One example is his attempt to acclimatise various plants, which means adapting the plants to a new environment.

The unsuccessful experiments did not help strengthen his legacy in the academic community. He was nevertheless considered a hero by the horticultural societies he helped establish.

“Despite a few unsuccessful attempts at acclimatising plants, he did help many people learn about horticulture and was able to spread his knowledge,” Siem says.

Today, several botanists have revived Schübeler’s work. Members of the KVANN Norwegian Seed Savers organisation are working on restoring his research stations throughout the country.

“For a while, Schübeler was forgotten in the history books. But he has once again become an interesting figure to look at in light of our climate challenges,” Siem explains.

Public education in the era of specialisation

Schübeler’s dedicated dissemination and organisation efforts did not lead to recognition in the academic community.

As a scientist, Schübeler faced challenges when he demonstrated his commitment to spreading knowledge to benefit a general public.

“He helped a lot of people get started with horticulture, but it resulted in a lot of debate within the academic community,” Siem says.

Nevertheless, Schübeler made sure to disseminate scientific knowledge through various media. But he had to fight to be taken seriously.

He drew criticism from those who considered his exhibitions and horticultural books for the general public to be ‘modern nonsense’.

Several horticultural societies’ chronicles refer to him as the individual who made the greatest contribution towards the spread of horticulture in Norway.

Interdisciplinary work required

Schübeler was not the only one passionate about public education.

Siem explains that his ‘partner in crime’ was the fairytale collector Peter Chr. Asbjørnsen, who was also a naturalist.

Asbjørnsen and Schübeler helped each other identify opportunities for funding in order to publish the work they considered to be both important and interesting. They also helped one another collect plants, animals, objects, and information that could contribute to their work and passion.

“Their shared passion for natural history is visible from the letters they wrote to one another,” Siem says.

She believes that the way in which the two of them worked to create networks within and outside of academia is now relevant again. Siem references the current academic ideal of interdisciplinary work to solve major societal challenges, especially in relation to climate change.

The Museum: a place to apply your knowledge

Schübeler’s exhibition at the Botanical Museum and Garden also helped him gain the influence required to make such useful connections.

He was a curator at the Botanical Museum in the 1850s and the manager of the Botanical Garden in Oslo from the 1860s. With the museum and later the garden as his base, he taught people throughout the country how to apply the knowledge he had collected.

“Not everyone believed that the garden should be used to teach horticulture to the people. They felt that someone who worked at the Botanical Museum and Garden should focus primarily on science,” Siem says.

She believes that the museums of today could learn from the way in which Schübeler spread his knowledge.

“We can also use museums and botanical gardens in this way today, to teach skills that can be useful in everyday life,” she says.

Siem envisions museums that not only inspire the general public but also initiate larger projects with knowledge from university and museum research.

She believes that this could help create new cultural practices, organisations, and even businesses and careers.

"It is a major undertaking. But I hope that by looking at how it has been done in the past, we can be inspired to take more risks in the present," she says.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family