THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

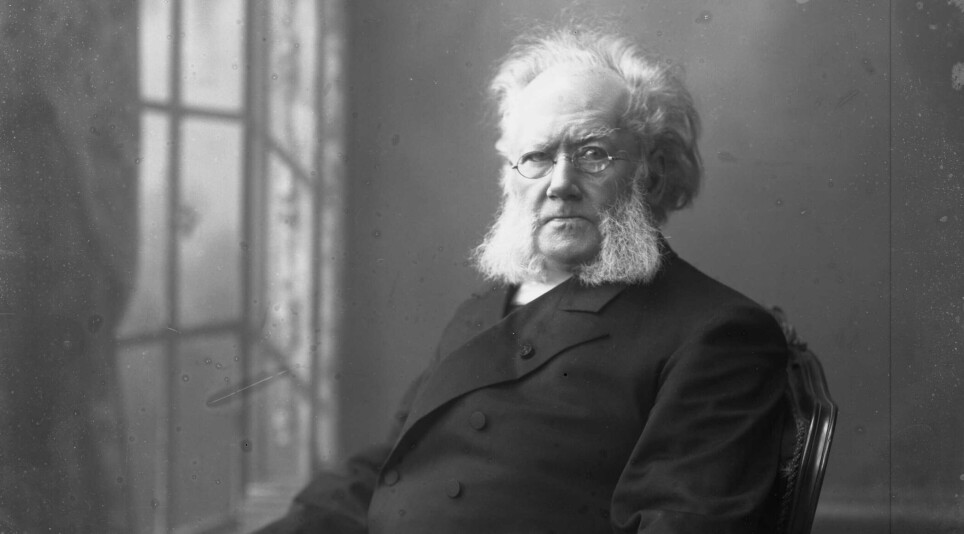

Ibsen's international success is a tale of rewrites and copyright piracy

The lack of copyright protection plays a big part in the story of Henrik Ibsen’s rise to stardom, argues Giuliano D’Amico in a new book.

Peer Gynt. A Doll's House. Ghosts. Henrik Ibsen's plays have been read and seen all over the world.

“The number of books Ibsen sold in Scandinavia and abroad was phenomenal,” says Giuliano D'Amico from Centre for Ibsen Studies at The University of Oslo.

But that does not mean that Ibsen immediately became rich from sales abroad.

“He was not protected by copyright, which means that in principle anyone could translate and publish his books, or produce his plays in theatres, without having to pay him.”

In the new book Ibsen in Context, D'Amico contributes with a chapter where he describes how the lack of copyright affected Ibsen's international career, particularly in the 1870s and 1880s.

The fact that there were no laws and regulations to ensure that the author of the popular plays was paid did not only result in a lean wallet. It also meant that European audiences were presented quite different versions of Ibsen's works than Norwegians read in the originals.

“Nevertheless, the lack of copyright contributed to Ibsen becoming a world class writer – at home and abroad,” D'Amico says.

Staging Ibsen was free

To become acknowledged in Europe in the 19th century, it was important to make it big in Germany. Ibsen made his way to many German bookshelves.

Up until 1917, 4.5 million copies of Ibsen's books had been printed in German. The powerful publishing house Reclam sold these cheap pocket editions, and hardly paid any royalties to the author.

“One might wonder whether they would have printed or sold as many books if Ibsen had been protected by copyright,” says D'Amico, adding that the same thing happened with stage productions:

“Pillars of Society in particular was performed often in Germany in the late 1870s. This would of course not have happened, if the audience had not liked it. But it was very lucrative to produce Ibsen’s plays, precisely because they were free of charge.”

Ibsen wrote letters about money

In 1886, the Berne Convention, which was intended to ensure authors the right to be paid for their works outside their home country, was adopted.

But neither Norway, nor Denmark, where Ibsen's publications legally belonged, ratified the convention.

“The Scandinavian countries imported a great deal of literature from abroad, and feared a situation in which foreign literature would become very expensive.”

Ibsen was frustrated with the situation. D'Amico has read through the letters Ibsen sent at the time, among them many business letters.

“He asks people to pay him for the work he does, and he seems very concerned about being in control of his own finances.”

The playwright also wrote to the Norwegian government.

“In the 1870s, both Ibsen and Nobel Laureate Bjørnstierne Bjørnson understood that they had a market abroad, but that they were not getting paid. In the early 1880s, they wrote to the Norwegian government saying that this was unacceptable. But while Bjørnson argued that Norway should enter into agreements with other countries, Ibsen realized that it would raise the price of literature,” D'Amico says.

“Ibsen then said that ‘as a good Norwegian’, he hoped that the government would raise the Poet’s allowance.”

Parallel markets

Ibsen understands that he cannot change the system, and instead secures payment wherever he can. He establishes a network of publishers and theatrical agencies all over Europe. These are granted the rights to the official translations of his works, while the unauthorized translations are relegated to a life on their own.

Thus, some people read Ibsen's authorized translations, while far more got their hands on a cheap pocket edition. Ibsen accepted this, and in Germany he even asked his main publisher to let Reclam continue.

“Although he loses money initially, it helps him reach a large readership. It may also mean that more people start going to the theatre,” D'Amico points out.

D'Amico believes Ibsen's lack of rights when the works were translated and published in Germany undoubtedly had a major impact on his international success. Nevertheless, the Ibsen researcher finds it difficult to speculate about whether Ibsen would have been as great if copyright law had been different.

“He probably would have achieved success anyway, but we cannot know whether it would have happened later, or if he would have had as much impact as he did.”

Free to embellish controversial content

The fact that anyone who wanted to could publish translations of Ibsen in Europe had consequences, not only economic but also artistic.

“Ibsen may seem a bit stingy, and he probably was. But the lack of copyright protection also meant he had no control over his own art,” D'Amico explains.

In A Doll’s House, the protagonist Nora chooses to leave her husband and children. At the end of the 19th century, this was controversial, and when the play was performed in Germany in 1880, it was given an alternative ending: Nora stayed with her husband Torvald.

Ibsen had rewritten the end of the play himself.

“He wasn't afraid of the German audience; this was instead a matter of copyright issues and pressure from an agent. Ibsen realized that the agents wanted a different ending, and that if he didn't write it himself, they would.”

Nora was not the only one to encounter an alternative fate on the theatre stages of Europe. In 1881, Ibsen wrote the controversial play Ghosts, in which he addresses infidelity, venereal disease and double standards. The play was censored in many European countries, and was therefore a failure. Except in Italy.

“In Italy, they made major changes to Ibsen's texts: they simplified and cut texts, and made them more sentimental. Ghosts went from being a terrible tragedy about a mother who cannot break free from a marriage, and a son who has been diagnosed with syphilis, to a melodrama about a poor, suffering artist. This became Ibsen's most successful piece in Italy: people loved it.”

Giuliano D'Amico supposes Ibsen was not exactly satisfied with this, but the researcher also believes it is an example of an artist who sometimes has to compromise.

“There is always a tension between autonomy and the market. There is, and has always been, a middle ground, between being 100 percent uncompromising on behalf of art, and writing commercial blockbusters for the sake of money.”

Ibsen is second to none

Copyright regulations are just one of the many perspectives explored in the book Ibsen in Context, published as part of a prestigious series by Cambridge University Press.

“Here Ibsen is found in the company of a series of English-language classics, as well as authors such as Marcel Proust and Fjodor Dostoyevski. This confirms Ibsen's status in the world,” says Tore Rem, who edited the book together with Narve Fulsås from UiT – The Arctic University of Norway.

According to Rem, studying the context in which Ibsen wrote is crucial when wanting to understand how a merchant’s son from the small town of Skien could become part of world literature.

“It’s about understanding how the Ibsen phenomenon was possible. In order to do this, we must study both his Nordic originating contexts and his global reception.”

In the book, a number of Scandinavian and international researchers follow Ibsen from early reception in Scandinavia and Europe to recent productions in Japan, China and India.

“We see that there is still a huge interest in Ibsen, and in the book we disseminate new research and encourage new readings of his texts,” Rem explains.

Both Rem and D'Amico emphasize that Ibsen is not merely a Norwegian writer.

“There are many, many Ibsens. You have a German Ibsen tradition, a French Ibsen tradition, an English, an Italian, and so on. And the different conceptions of Ibsen around the world are, among other things, the result of a lack of copyright protection,” D'Amico says.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"