An article from University of Oslo

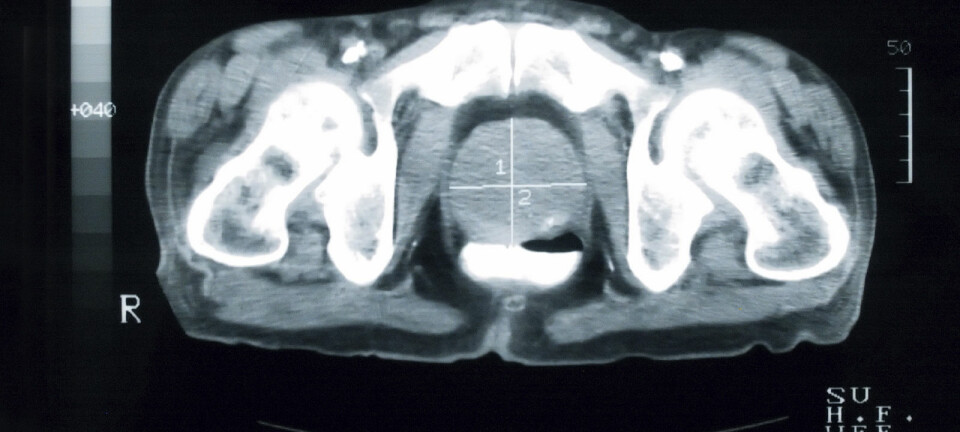

The hunt for prostate cancer

New biomarkers can make hunting for prostate cancer more accurate.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer among men. One in eight men will be affected during their lifetime.

But not all forms of prostate cancer are as aggressive, and not all require the same extensive treatment. The challenge is to identify the different types.

Vesicles hold the secret

The answer may lie in vesicles, and scientist Alicia Llorente is working to crack the code.

"Vesicles are small bubbles of liquid found in all biological fluids. All cells secrete vesicles for a specific purpose," she explains.

Just like any motorist trying to find the fastest and least winding road, Llorente is trying to find the easiest and most accurate way of detecting prostate cancer. She wants to drive on the highway, not a crooked county road with an uncertain destination.

Her research group is working on intracellular transport. They are studying how molecules are transported into cells and how they move from organelle to organelle inside the cells.

The different organelles are like small workshop artisans, each of whom has a special function. There is constant movement in a cell. Proteins and other molecules move constantly, not only inside a cell, but also from cell to cell via the vesicles.

The biological detector

A biomarker can be compared to a snitch who tells you that cancer has arrived. It's a molecule that shows whether a person is healthy or sick.

"The molecule makes the difference. A sick person has it, a healthy person does not," says Llorente.

Many biomarkers are found in tissues. Consequently, biopsy always involves a surgical procedure to a greater or lesser degree. Llorente is working to find biomarkers in the vesicles present in biological fluids such as blood or urine.

The biomarker used to detect prostate cancer has been used for many years, and is called Prostate Specific Antigen, PSA. While this marker is in the blood, it has a relatively large margin of error.

"A high PSA may indicate cancer, but can also be a sign of inflammation in the prostate," she says.

This means that people can be diagnosed as cancer patients, without having cancer. They undergo extra biopsies and additional treatment. In addition, they suffer the mental strain of being diagnosed with cancer. Scientists are therefore working to find new biomarkers that hit the target more often.

A higher degree of precision

In some cases the cancer is not very aggressive and grows slowly. Patients with this form of prostate cancer can live with the disease for many years, without the equally comprehensive treatment that people with a more aggressive type of cancer must undergo. The problem is that the accuracy level of the biomarkers used today is not high enough.

This makes it difficult to distinguish between the various types of prostate cancer. Which one requires immediate treatment and which is a less aggressive variant that does not require the same treatment?

Llorente wants to find the answer.

"Using biomarkers that are more precise will make it possible to specify the type of cancer and provide a more accurate diagnosis. It will be possible to distinguish between aggressive and slow-growing variants," she explains.

Such accuracy will benefit hundreds of patients in Norway every year.

Dispersal mechanisms

Vesicle secretion is an important communication mechanism that takes place between cells. The information exchanged between healthy cells is harmless. It is only when cancer cells secrete vesicles that there is danger afoot.

The reason is that vesicles from tumour cells transmit harmful molecules to surrounding cells, causing the cancer to spread.

"This is at least what the research suggests," emphasises Llorente.

Researchers are trying to find the mechanisms the cells have for secreting vesicles precisely because vesicle secretion is believed to contribute to the spread of cancer.

"We are trying to identify the secretion mechanisms, and to prevent them from working. If we can stop the secretion of vesicles from tumour cells, this could be a possible treatment for cancer patients," says Llorente.