THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

Geese can impact the permafrost on Svalbard

Sharp beaks tear into the moss.

Svalbard is becoming greener. As the air gets warmer, giving the tundra more to offer, birds are tempted to migrate further north. Flocks of geese feast in the valleys with table manners that both enhance and work against the greening.

“The tundra looks as if a lot of people have been hiking there with poles,” says Lise Øvreås, describing valley floors perforated by goose beaks.

The professor at the University of Bergen's Department of Biological Sciences and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research coordinates a research project on birds and permafrost.

The aim is to find out how grazing geese influence the thawing ground as well as its microbes and plants.

“Moss is important. Moss keeps the soil cool, humid, and stable,” she says.

When large flocks of geese search for food, they chop up the insulating layer of moss that shields the ground from sun and mild summer air.

Warmer weather is obviously the most important factor behind the thawing of permafrost. But what happens when thousands of beaks dig into the moss?

How much of a menace can a goose be?

Pretended to be birds

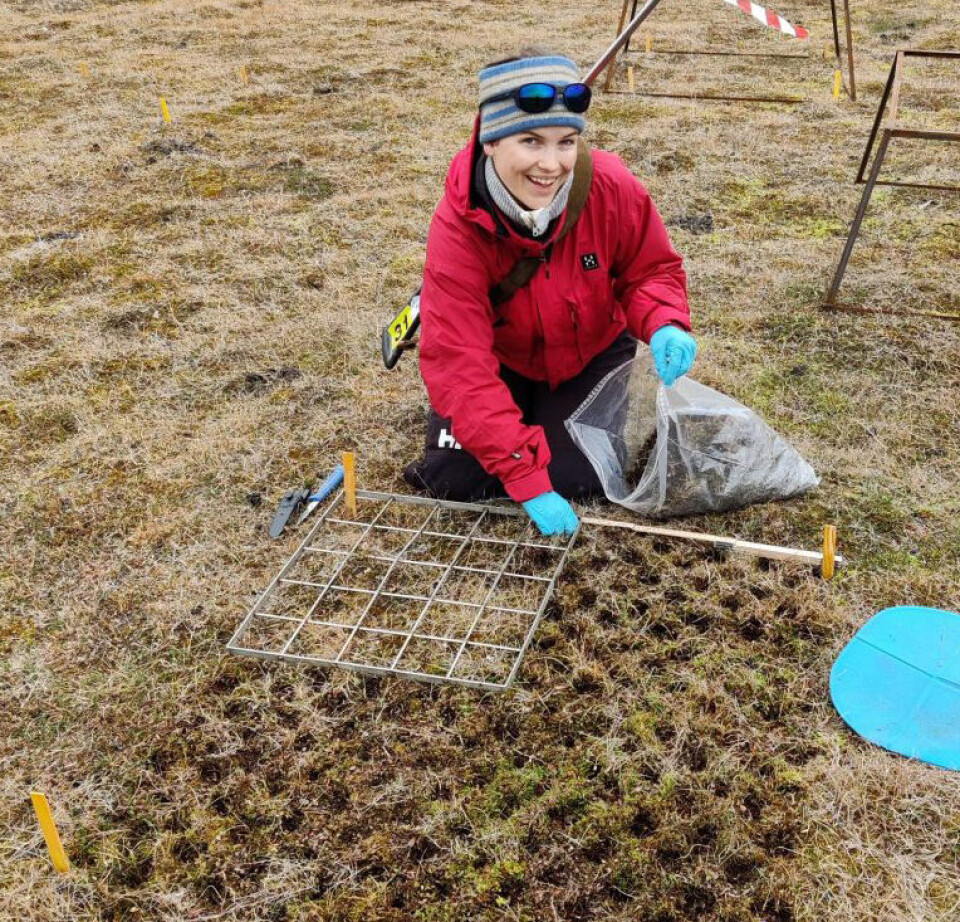

In the valleys around Longyearbyen, biology professor Øvreås and colleagues from the University of Bergen and the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) have marked off small plots of land, each about one square metre.

Each patch represents specific characteristics of the tundra: with or without species like Dryas octopetala and Salix polaris. With or without ice in winter. And most importantly: With or without pecking beaks.

“We pretended to be geese and rubbed and picked at the moss,” she says.

Lise Øvreås forms a goose beak with her hand and chops in the air to illustrate the work of researchers and birds.

Thawing permafrost is associated with collapsed houses and sinkholes. But the changes also have smaller-scale consequences for plants and microbes in the soil.

When the frost no longer acts as a barrier, bacteria and other microbes move deeper.

The microbes are also influenced in other ways. Geese do more than merely expose frozen ground.

Goose droppings turn the valley green

“They poop like crazy,” says the professor.

In recent years, Lise Øvreås has seen the tundra becoming greener in the geese's grazing fields. Not only do the birds poop, they poop in their own food tray, with great success. They fertilise the soil with nitrogen, which Svalbard plants otherwise have limited access to.

To find out how much this additional supply of nitrogen means, the researchers collected a kilogram of goose droppings, dried it, and distributed it in their test field.

Fertilisation would have limited benefits if not for the microbes beneath the soil surface.

Plants cannot absorb all forms of nitrogen from the soil, and certainly not from the air. Their uptake depends on interactions with bacteria.

In goose droppings, nitrogen is present in the form of ammonia, which plants can absorb directly, unlike nitrogen gas. However, absorption is more efficient when microbes first convert ammonia into nitrate.

Beneficial cohabitation

The roots of pea and raspberry plants have tubers containing rhizobia – soil bacteria that fix nitrogen from the air and pass it on to the plant.

On the mainland, where plants and trees are abundant, this symbiosis between plants and rhizobia is important. Though sparse, the vegetation in Svalbard has been shown to be richer in rhizobia than previously assumed.

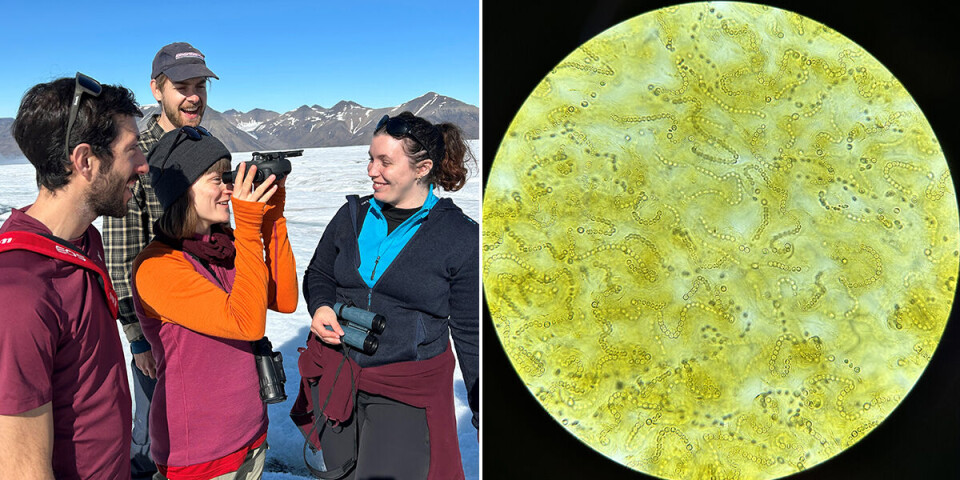

“Cyanobacteria,” says Lise Øvreås. “Large, green blobs of rubbery flakes you can pick up. We find a lot of these in Svalbard, and they also fix nitrogen.”

"These are large, green blobs of rubbery flakes you can pick up," she says.

The field microscope she always carries is sufficient to see the glass-like cells the flakes consist of. These cells absorb nitrogen from the air and make it available to plants.

Plants might get less nitrogen

Traditionally, cyanobacteria have been considered important for providing tundra plants with nitrogen. The question now is whether this will continue to be the case.

“Recent research suggests that biological nitrogen fixation has been optimised for low temperatures, so that the climate change now seen in the Arctic, may lead to a decrease,” says Lise Øvreås.

After two years of measurements, the researchers have packed up their equipment. Now, the analysis of all the data they have collected remains, including nitrogen, carbon, temperature, humidity, ice, and, most importantly:

“Moss,” says Lise Øvreås. “Gases have been trapped in the permafrost for thousands of years. Now they are being released.”

The geese have flown south, but will soon return.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

The proteins in your blood can reveal early signs of heart problems

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early

-

Researcher: Politicians fuel conflicts, but fail to quell them

-

The West influenced the Marshall Islands: "They ended up creating more inequality"

-

Banned gases reveal the age of water