THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY Oslo Metropolitan University - read more

The strange and deadly consequences of bacterial sex

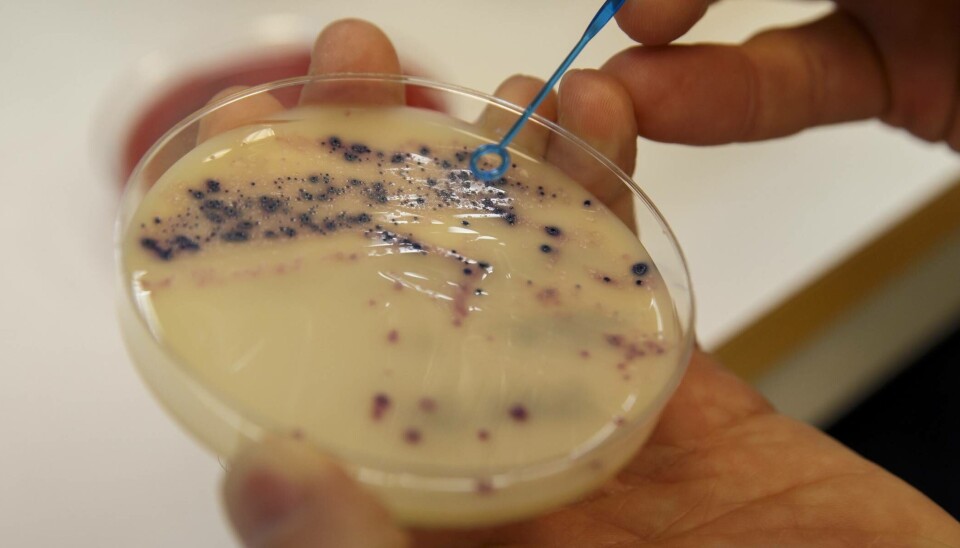

Bacteria that resist antibiotic treatment represent a significant public health challenge. How and why does bacteria exchange DNA — and how can they be prevented from doing so?

Since coming to OsloMet in 2016, Ole Herman Ambur has been tackling one of the biggest questions in biology since before Darwin: What is the adaptive value of sex? Literally — why do we do it?

Combining DNA from different individuals can give an organism many advantageous new traits. However, acquiring such DNA requires expending energy and can expose the organism to dangers.

So why does this ability keep evolving?

“There are several hypothesises about this going back to the 1880s. Now we have a chance to investigate this by doing evolution experiments in the lab,” Ambur says.

What is bacterial sex?

Before we can start investigating, it is worth clarifying a few terms. In casual use, sex can mean many things.

“It can mean physical characteristics, the act of having sex, or reproduction,” Ambur explains. “But in the microbiological world, we understand sex as unifying DNA from two different individuals into one.”

For Ambur and other microbiologists, reproduction and sex are different things. In many ways, they are even opposites.

Reproduction in bacteria, like most single-celled organisms, happens by copying DNA and splitting into exact duplicates. This is great for stability of the species, but it leaves little chance for creating new genetic adaptations that help the bacteria survive when their environments change.

For that, they need to exchange DNA.

They need sex.

Many physical characteristics like body size and shape are controlled by DNA sequences called alleles. In humans, these alleles determine things like hair or eye colour. Sex lets organisms swap alleles to get new traits.

New alleles might give bacteria faster movement or resistance to toxins and antibiotics. On the other hand, a new allele could also damage the fine-tuned cellular machinery and cause the organism die.

When sex does give them an advantageous trait, it’s great for the bacteria, but could be deadly for us if the ones inside us gain the ability to cause disease.

Fears of resilience in pathogenic bacteria

Ambur explains that pathogenic bacteria, the ones that can make us sick, gaining resistance traits is one of the scariest things from a health perspective.

His research follows a World Health Organisation (WHO) mandate to seek new ways of fighting antimicrobial resistant bacteria, or AMR.

AMR are insensitive to even our strongest medicines. They are a huge problem in today’s healthcare system. Over a million people die each year from AMR, more than from HIV or Malaria.

Balancing the good and the bad

The bacteria that live in and on our bodies exist in a careful balance. We are dependent on this symbiotic relationship. They do helpful things for us like break down food, make essential vitamins, and make it difficult for dangerous species to get a foothold.

In return, we give them a safe, food-filled place to live — and have sex.

Bacterial sex is fine when the helpful bacteria become stronger. But when their pathogenic relatives show up and exchange resistance alleles, they create a problem.

When bacteria acquire new alleles that let them out-populate the other bacteria in us, they can disrupt the balance and make us sick. When they also get resistance abilities, they can become unstoppable.

“Looking at the evolution of AMR can tell us about the underlying machinery of that process, and we believe sex is a core part of that,” Ambur says.

Sex is an adaptation that makes bacteria resilient. For a bacterium, this could mean surviving against our immune system or exposure to antibiotics.

There was a time when we were able to easily treat diseases like gonorrhoea. AMR means we no longer have an effective way to handle such infections.

Bacterial sex exacerbates this problem by spreading these resistant alleles to new bacteria.

Hijacking the process

Now, thanks to new technology, Ambur is able to understand the evolutionary value of sex and predict new ways to disrupt it.

“Now we have a chance to explore Darwin’s great theory of evolution by means of natural selection in real time. We can study the evolution of sex and its adaptive value,” he says.

The OsloMet researcher is using a technique called high throughput DNA sequencing, that can quickly identify the entire genomic sequence of a bacteria. A process that used to take months or even years can now be done in a single workday, with time left for lunch breaks.

This, combined with massive public genome databases, has created a treasure trove of genetic information for Ambur and his team.

They are using this information to trace how the alleles are swapped in real time by following a small genetic marker the bacteria use to recognise their own species and sexual partners.

Ambur and his team of bioinformaticists, phylogeneticists, and bioengineers, found that these genetic 'words’ change subtly over time and form different dialects the same way human language does.

Tracing these words and checking each generation, Ambur can identify the specific genetic pathways that allow the bacteria to acquire resistance alleles.

Using this information, he can figure out ways to block this sexual transfer, a bacterial contraceptive if you will, or even create new treatments for AMR by hijacking the process to trick the bacteria into sharing alleles that will kill them.

Exciting developments

“The science is exciting and engaging and we are finding phenomena that are new to science,” Ambur says.

Understanding how and why bacteria have sex opens up entirely new avenues for future research.

Seeking out alternative strategies for intervention is a step toward fighting AMR infections.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by OsloMet

This content is created by Oslo Metropolitan University's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. Oslo Metropolitan University is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from OsloMet:

-

Ukrainian refugees need jobs. So why aren’t more of them being hired?

-

The mural in Oslo City Hall conceals a dramatic story – about the artist’s own life

-

Mental health problems are widespread among Ukrainian refugees

-

Only 1 in 10 Ukrainians want to return

-

How class divisions are maintained in Norway

-

Many adolescents think they're not interested in politics – until a teacher gets them to reflect on their own lives