This article was produced and financed by Nofima The Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research

Eradicating the spores

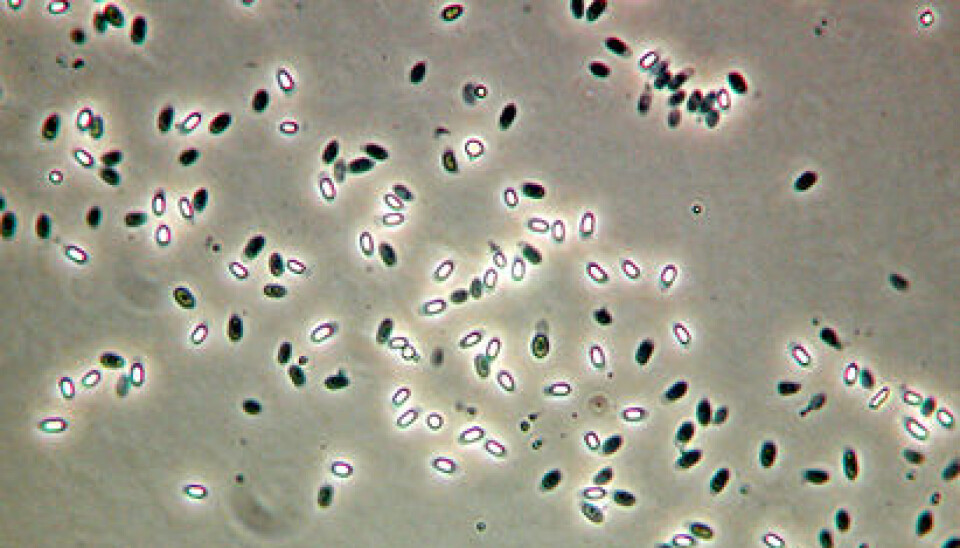

Spore-forming bacteria are one of the greatest microbial challenges to food safety in ready meals, and a single heat treatment at 70–80° C can in fact stimulate the growth of certain bacteria. But could a double heat treatment of ready meals increase the safety?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“The spores’ state of dormancy is quite simply an incredible strategy for survival, one that gives the bacteria an advantage in the microbial world,” says researcher Thomas Rosnes.

Spores can survive in dry ingredients for several years. All the genetic material is stored in the spore, and the biochemical life processes can resume by means of an advanced signaling system. When advantageous conditions are present, such as sufficient nourishment, moisture, and suitable temperature, the bacteria are revivified – as can happen in today’s heat-treated ready meals.

Spores in ready meals – a challenge for the producers

There has been an explosive growth in the market for chilled ready meals that consumers can swiftly heat at home prior to eating them. The ready meals are sufficiently pasteurized to kill bacteria that do not have spores, such as E. coli, but Bacillus spores will often be able to survive such heat treatment.

In many ready meals Bacillus will therefore not have any competing flora, and they lie dormant in closed spores with sufficient nourishment. The objective is to ensure that such bacteria do not pose any risk to the food.

Several strains of Bacillus in the food

The bacteria can produce toxins (poison) either in the food product itself or upon entering human intestines. It is important to acquire more knowledge in this area, and the experiments that Nofima and its partners performed on two strains of Bacillus show that a heat treatment of 70°C for 15 minutes might in fact activate the spores.

Such activation helps switch off the stable heat phase and switch on the biological mechanisms that enable the spore to grow.

It also turns out that the active phase that follows heat treatment can be maintained for up to a week at 6°C. This suggests that the spore would be ready to germinate and grow if for example the storage temperature increases later on during the product’s shelf life.

From molecular biology to practical use

It is important to understand which biochemical and physical factors are necessary for germination to commence and for growth to continue, so that procedures can be established for killing the spores or controlling the growth. In one experiment researchers added spores of B. cereus as well as certain elements that stimulate germination, and heat-treated the mixture at 70°C for 17 minutes.

They followed this up by lowering the temperature to 30°C to allow the activated spores to germinate. When they subsequently heat-treated the mixture for the second time at 80–90°C for 12 minutes, the spore content was significantly reduced.

“This shows that companies are able to achieve both a higher food quality and a higher food safety by choosing the correct procedures for heat treatment,” Rosnes says. “At optimal conditions the double heat treatment can give both a lower cooking temperature and have a corresponding or better reduction of spore content, compared with a single heat treatment," says Thomas Rosnes.