THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

Manga: Social criticism in comic strip form

In the 1970s, Japanese comics transported their readers to ‘exotic Europe’ when characters engaged in activities that were taboo and the Japanese society was to be criticised.

Spiky hair, exaggerated expressions of emotion, and large eyes. These are some of the typical characteristics of characters in manga – Japanese comics.

Manga has become a cultural phenomenon, with many of the stories being adapted into animated films, TV series, and games.

“There is manga for children, for the elderly, for all ages really. They can be about sports, erotica, history, science fiction, or current social issues. There is probably not a single topic that cannot be discussed in manga,” Rebecca Suter says.

She is an associate professor in Japan Studies at the University of Oslo. Suter has recently contributed to the book Reconsidering Postwar Japanese History: A Handbook, in which she has written a chapter about manga’s role as a builder of identity in postwar Japan.

From the postwar period up until the 1970s, there were socially critical manga written by authors on the political left. They dealt with, among other things, the difficult conditions of the working class and outsiders in society.

The West as free and exotic

A form of manga that has fascinated Suter are those set in a European context. Japanese manga authors primarily set their stories in France and Germany.

They are detailed and realistic, and many of the authors travelled to the countries themselves to study the architecture and culture.

“It is interesting to see how they use Europe as a kind of fantasy world where the characters can do things that were not possible in Japan. Here, the characters have more freedom, not least sexually,” Suter says.

The genre was especially popular in the 1970s and 1980s. Suter describes this exotic portrayal of Europe as a kind of ‘reverse Orientalism’.

The term Orientalism originates from literary historian Edward Said and refers to the West's stereotypical perceptions of countries in East and Southeast Asia, often referred to as the Orient.

‘Boys love’ in Germany and France

Among the most popular stories set in Europe were those known as ‘boys love’.

These are stories about homosexual relationships, often set in boarding school environments in France and Germany in the 1920s. The stories were not written solely for entertainment, but also contained social criticism, Suter points out.

“The authors placed the action in the distant and exotic Europe to criticise Japanese society from the outside. It was safer to have some distance when the stories revolved around homosexuality and challenged traditional Japanese conventions,” she says.

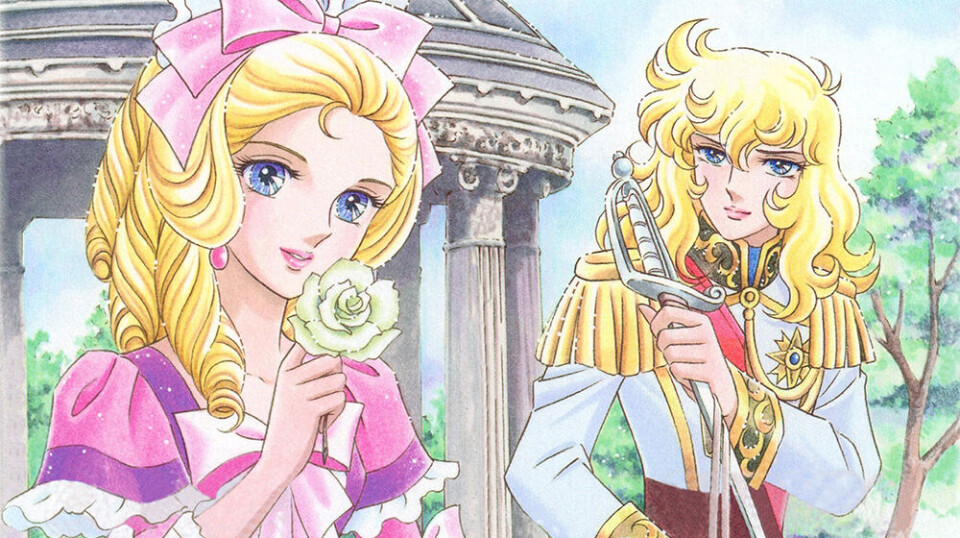

One of the most famous stories is The Rose of Versailles, which is set in France during the time of the French Revolution.

The main character, Oscar, is a girl who has been raised as a boy and becomes captain of the royal guard.

“Cross-dressing, or dressing as the opposite gender, is a major theme. This is not just wild imagination, but a way to present readers with a world in which there is more freedom and choice,” Suter explains.

The hospitable Europe

In a new research project, Suter is set to examine a trend in Japanese manga from the past 20 years: Stories that take place in the Nordic countries and around the Mediterranean.

Despite being located at opposite ends of the European map, these countries are portrayed as cultures with many similarities.

“I call this ‘the new West’ or the ‘alternative West’. These countries represent the West, but at the same time, they differ from the stereotypes. They're presented as something more exotic, yet more similar to Japan, compared with the series set in Germany and France,” Suter explains.

One similarity with Japanese society that she sees highlighted is the closeness to and the appreciation for nature, as well as the cultural significance of ‘motenashi’ – the Japanese word for hospitality.

“Japanese people like to portray motenashi as something unique to Japanese culture. But in manga, we see that Swedes and Italians can master motenashi as well,” Suter says.

Criticising Japanese work culture

Japan is known for its demanding work culture, where long hours, overtime, and limited vacation are common.

In the manga Suter has examined, countries in the Mediterranean and Scandinavia are often portrayed as the opposite of this, with a focus on a relaxed lifestyle and a good balance between work and leisure.

“One story is about a couple that moves to Sweden. When they get home from work, it's only three in the afternoon. They're overjoyed about the fact that they still have the whole day ahead of them,” Suter explains.

It is primarily the positive aspects of Nordic and Mediterranean culture that are portrayed. Family and more time for friends are also important elements.

“They indirectly point out something that doesn't work so well in Japan – this idea of work-life balance. By showing how well this works elsewhere, it is a form of criticism of Japanese society. It's a gentle way of criticising,” Suter says.

Is manga uniquely Japanese?

How uniquely Japanese is manga really?

There are different approaches to this question – from those who draw a direct line from Japanese traditions from the Middle Ages to the present day, to those who point out that manga is also influenced by Western culture.

Suter belongs to the latter group. It wasn't until the late 19th century that manga became an established term for comics in Japan.

“The first comics in Japan were inspired by the European and American humor magazine tradition. In the 20th century, it became common to have humorous comics in newspapers, like in the USA. However, the themes and scenes were from Japanese society,” Suter says.

As Suter sees it, Japanese manga developed its distinctive expression as we know it today in the 1950s. They became an important part of Japanese postwar identity.

Manga as cultural export

For many, Pokémon is the first encounter with characters that have a typical manga appearance. Pokémon became so popular at the turn of the millennium that it sparked a global phenomenon known as Pokémania.

“The idea that manga is a distinct expression of Japanese culture was something that Japanese authorities began to promote in the 2000s,” Suter explains.

In the 1990s, several European manga authors emerged, and in 2006, the Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs initiated the creation of a new award, The Japan International Manga Award to honor the best foreign manga authors.

“Manga was used to generate buzz about Japanese culture,” Suter says.

In Norway, a genre called ‘Nordic manga’ has appeared, a term coined by the publishing house Egmont, according to the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK).

The book series Nordlys, which is rooted in Norwegian folklore and fairy tales, is often highlighted as a catalyst for the genre.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"