An article from University of Oslo

Design history provides clues about the future

Design is not merely creating something. Design can kill, and design can bring about global progress. Visions of a more sustainable future can be found in the history of design. Now these visions are being dug up.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Today sustainability is a basic principle in all design practice including design education, research and dissemination. But the history of this ‘green revolution’ and how it came about has not yet been written.

Kjetil Fallan, Professor of Design History at the University of Oslo, sees this as a problem.

“It’s about understanding the crucial role design plays in the development of a more sustainable society. If we are to find successful strategies for a better, more sustainable society, we must know how we ended up in the situation we’re now in. We must be familiar with the strategies developed earlier. It is essential to create a solid knowledge base for new decisions,” he says.

Fallan heads a new three-year research project: Back to the Sustainable Future: Visions of Sustainability in the History of Design. The aim of the project is to ensure that the hitherto unexplored history of sustainable design is manifested and utilized in a greater range of humanistic disciplines.

Wants to highlight the ambivalence of design

The researchers intend to explore the period from the sixties up to the present.

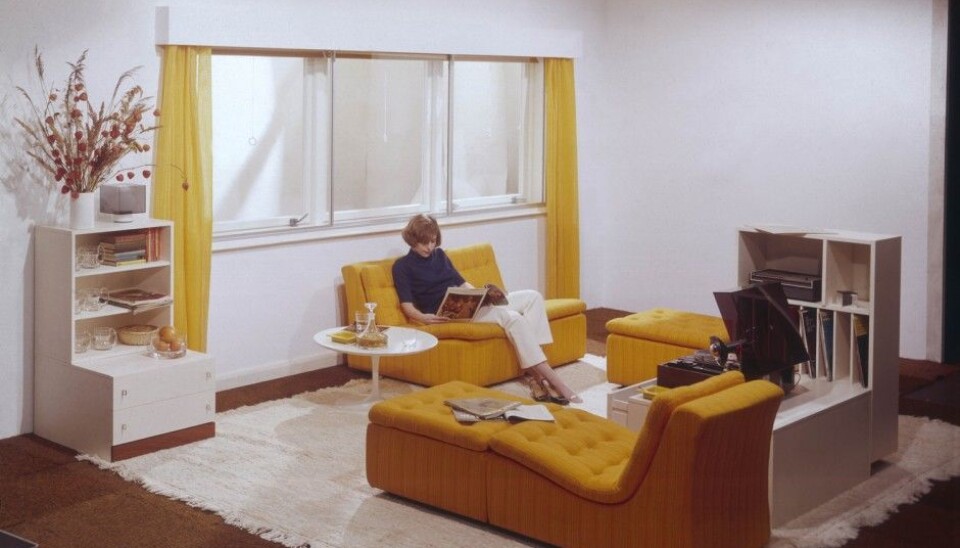

“Dramatic changes have taken place in this period,” says Professor Fallan. Not only does he point to the development in welfare and the explosive growth in consumption but also to the environmental movement and other contemporary counter cultures. In the sixties, photographs of huge landfills in the US illustrated very effectively the underbelly of the consumer society. The recognition of this also created a feeling of crisis in the design world.

Fallan refers to a well-known quotation from the book Design for the Real World in which the author, Victor Papanek, claims that industrial design – with its mass production and the ensuing littering and pollution of the environment – kills. Designers have become a dangerous race, Papanek wrote in 1971.

“The view of the designer as a problem solver was dealt a severe blow. Designers started to criticize their own profession, asking the question: ‘Maybe design actually causes more problems than it solves?’”

Both are true, Fallan points out:

“What Papanek did was to highlight the ambivalence of design. Design is not by definition good. It has the potential to solve problems but this is not inherent.”

More than industrial design

Sustainability is a problematic concept, Kjetil Fallan admits. In the business sector it is quite common to talk about economic sustainability in the sense of what ensures sufficient return for owners and investors.

“In our context it’s about ecological sustainability,” he underlines.

“Why hasn’t research been conducted into the history of sustainable design until now?”

“Yes, good question! The history of design has been closely linked to art history. That’s probably one explanation.”

But the research project is not limited to industrial design.

“If we are to answer all the questions related to design and sustainability, we have to include all kinds of production processes, not only the industrial ones. We want to study the design, planning and production of the whole of our material culture. However, it’s not things in themselves that we’re most interested in; it’s more the history of ideas, including the political aspects underlying the development of the designer’s role. We will be investigating how designers have related to visions of sustainability throughout the history of design but we’ll also be examining the role played by theorists, reviewers, educators and consumers.

The designer as a social activist

One of the goals is to discover how the notion of sustainability has changed throughout design history, says Kjetil Fallan, and gives some examples.

“The 50s was the golden age of Scandinavian design, and also the heyday of teak. But towards the end of the 60s the use of exotic hardwoods was criticized as being contrary to nature. At that time there was no talk about the importance of locally sourced rather than globally sourced materials but in reality that’s what it was all about. So that kind of thinking existed among designers in the 60s and that’s interesting.

The design historian also brings up the topic of social activism at the Norwegian National College of Art and Design in 1968. One of the lecturers, Roar Høyland, who taught design, hung up a large poster with the following text: We have enough teacups!

“Crafts played an important role then, particularly beautiful objects for the home. Høyland said ’No’ and the students were on his side.

“All the same, in spite of growing awareness of sustainability, haven’t we even more teacups today?”

”Yes. However, the picture is more complicated. We see projects like Design without borders and others that have the goal of achieving greater societal sustainability, for example. More designers are involved in small-scale production, and acknowledge the importance of sustainability by producing locally. But yes, the designer’s role today is absolutely problematic.

The history of sustainable design is an area of great interest for many others, not just design historians, Fallan asserts.