An article from University of Oslo

Translators leave strong imprints on literature

We read novels in translation with an idea that we are reading the original text. And that is the way we want it, according to researcher.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Perhaps the author was actually Latin American. Or French. Or Arab. And perhaps she wrote some passages that really would have been beyond us.

But what does it matter, when translators and publishers wave their magic wand and provide us with the world’s literary legacy in our own language, formulated in fully understandable sentences?

Cecilia Alvstad, leader of the research project Voices of Translation at the University of Oslo believes that all parties involved have entered into a pact that ranges from the manuscript to bedside reading. This pact enables us as readers to blindly disregard the intervening stages and read a short story by Dostoyevsky as though that is exactly how Dostoyevsky had written it. Reality, however, is different.

"The reader wishes to read Dostoyevsky or Shakespeare, she isn’t interested in the Norwegian translator. But the translator and all other involved parties obviously leave a strong imprint on the end product,"’ explains Alvstad.

Feminine features disappeared

In this project, the researchers have studied literature that has been translated into Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish and Danish, and they have studied the translator’s role in particular.

Their topics include how translators in the different Nordic countries have translated books in varying ways, whereby cultural stereotypes probably have helped produce varying end products.

Eva Refsdal, PhD scholar, found such examples when studying the translations of three Latin American books from the 1960s. Here, the Norwegian translators had toned down feminine features of male characters.

For example, a man who in the original version ‘spoke like a woman’ with a soft, squeaky and false voice had become a man with an ‘ugly, wheezing’ voice in the Norwegian version. Indications of homosexuality were also toned down in the Norwegian translations. Such patterns were not observed in the other Nordic countries.

"Perhaps this could mean that homosexuality was a more sensitive topic in Norway than in other Nordic countries in the 1960s. Or it could mean that more pronounced notions about Latin American men were prevalent in Norway. We do not mean to say that the translator has made a mistake; on the contrary, it shows that translation work often includes an element of adaptation and creativity," says Alvstad.

Adaptation to cultural expectations

She believes that even today’s translated texts bear the stamp of culture and social expectations.

"It’s difficult for us to see how translators adapt texts, because we’re part of it. The work that translators do is based on our own expectations," she says.

If there was an expectation in the 1960s that effeminate characteristics in Latin American men were implausible, a direct translation from Spanish would lack credibility in Norway. The translator would risk breaking the pact, and the reader would pause in bemusement. Such things are being adapted today as well. Features that stand out as implausible are changed.

A current example could be that of an experimental language with alternative grammar and spelling being translated into completely standard Norwegian.

"If the experimental language is translated directly, there is a risk of the reader believing that the translator doesn’t know proper grammar. Thus, translators who render the text with no regard for cultural expectations may end up by drawing attention to themselves."

Wishing to be fooled

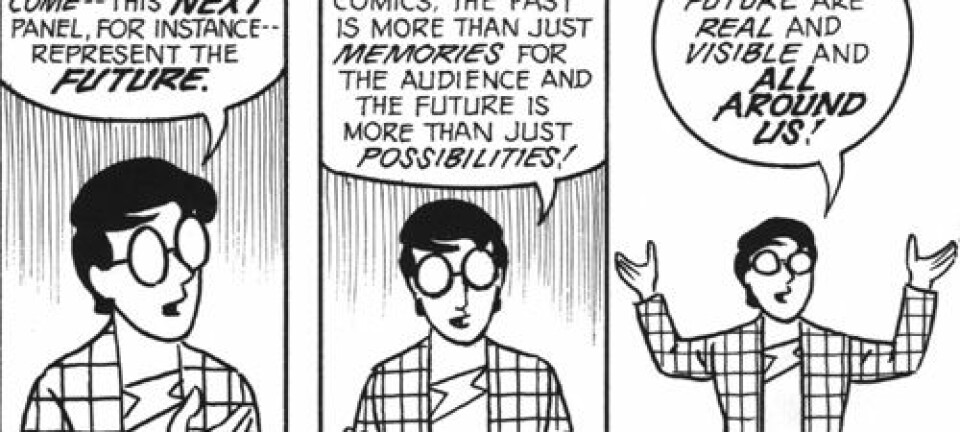

The book’s cover helps maintain the pact that Alvstad describes. The book’s title and the name of the author are highlighted, while the translator’s name is written in small type inside the cover. Occasionally, the translator nevertheless chooses to write a paragraph discussing any difficulties encountered in the translation work.

Although previous studies have indicated that this may help make the reader more aware of the translator’s role, Alvstad claims that it might rather serve to reinforce the impression that the text has been translated from the original language without any major changes.

"For example, we saw that one translator had written that the word “centro” was difficult to translate, and he explained the background for his choice of words. As a reader, one is easily left with the impression that this was the only troublesome word, and that the rest of the job was fairly simple. In this way the translator can play a little trick on the reader, and thereby reinforce the pact," Alvstad explains.

She points out that this is exactly what the reader wants: to be tricked.

The reader wants to maintain the idea that the translation does not change the text. This is a game in which everybody plays along.

The average reader is not the only one to disregard the translator’s role; critics and textbook authors do so too. Previous studies have indicated that the translator is often overlooked: critics may for example refer to specific formulations as though they were the author’s own, while they may equally well be the work of the translator.

Inventive co-creators

The pact that Alvstad describes in her research may conceivably help improve the reading experience, because we feel close to the original text.

Alvstad most certainly does not want to put an end to this pact, but she nevertheless points out that it may have certain negative aspects. For example, we risk perpetuating social prejudices. She also believes that translators remaining near-invisible may also cause readers to regard their work as quite mechanical and simple.

"If one looks really closely at what translators do, one can see that they are inventive co-creators and have a major impact on the text," Alvstad concludes.