This article is produced and financed by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Conflicting consequences of climate change for Arctic geese

Climate change is the big wild card when it comes to the survival of many Arctic species. A new study shows that climate change will be both good and bad for Svalbard barnacle geese populations — although the balance may tip depending upon the severity of future temperature increases and how other species react.

Life over the last half century has been pretty good for populations of Svalbard barnacle geese. A hunting ban implemented in the 1950s in their overwintering area in Scotland has led to explosive population growth — from roughly 2800 birds in 1960 to more than 40000 birds today.

But what will happen to these birds and others like them, which migrate to Arctic nesting grounds, as the climate grows warmer?

You might think that a warmer climate in the Arctic would only be beneficial, but shorter winters with earlier springs — as has already been recorded in places like Svalbard — are not necessarily good for birds that migrate there. Birds can arrive too late to match their breeding period with peak availability of their food.

And that’s just one possible issue raised by climate change. Another problem is that even when the birds can benefit from earlier springs, their predators can benefit from climate change, too.

Now, a team of researchers from Norway and the Netherlands has put together the puzzle of just how climate change affected a local Svalbard barnacle geese population. They’ve found that so far, climate change has been both good and bad for the birds — with a net zero effect.

“When you consider the earlier springs, it’s good news so far,” says Kate Layton-Matthews, a PhD candidate at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s Centre for Biodiversity Dynamics and the first author of the new study. “But the predation part outbalances the benefits from climate change.”

3487 birds over 28 years

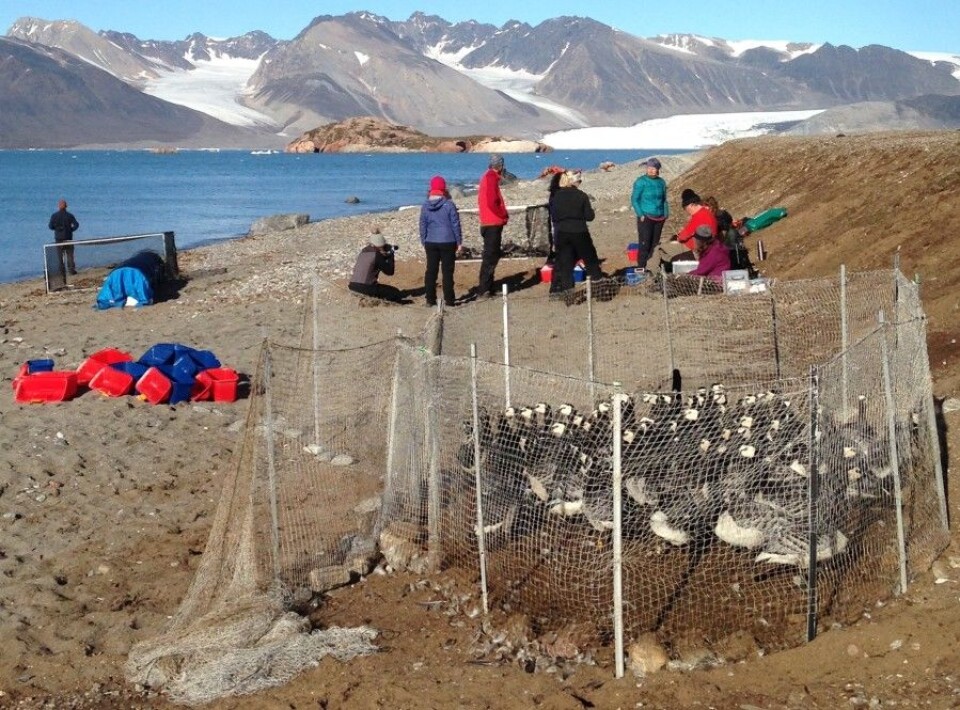

The researchers relied on data on from 3487 geese that have been collected since 1990 from Ny-Ålesund, a small town in the Svalbard archipelago.

Over that period, senior author Maarten J. J. E. Loonen at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands collected sightings and physical data from the birds — their number of eggs, number of hatchlings and much more — and also put rings on the birds’ legs so they could be re-identified, year after year.

That wealth of information allows the researchers to be able to track overall population changes and to combine population data with other measurable variables, such as temperatures, time of snowmelt, start of growing season and the like. Co-author Eva Fuglei at the Norwegian Polar Institute also collected annual data on the abundance of the main predator, the Arctic fox.

“I have been studying this goose population for more than 30 years, and have seen increasing complexity in explaining population trends. Too many factors were changing at the same time, including climate change,” Loonen said. “The beauty for me in working with the team in Norway is that they could bring many of these factors together, especially related to climate change all along the flyway. The long data series from the Arctic is unique in its detail, but also the spatial scale on which these migratory birds operated and are affected by climate change.”

In short, this huge complex dataset gives a detailed picture of the birds’ lifecycles and how and why this has changed over the years, especially as the climate has warmed.

Warmer springs and winters are beneficial

The birds fly to Svalbard from their overwintering grounds in Solway Firth in Scotland. Many of the geese stop in Helgeland, a coastal area in northern Norway, before reaching their nesting grounds in the spring, while others make the flight direct from Scotland to Ny-Ålesund, a distance of 3000 kilometres.

Once on Svalbard, the birds can lay as many as six eggs on islands off Ny-Ålesund. When the goslings have hatched, the birds move inland into the tiny town, in search of more food for them and their young.

All of these different steps in their life cycle can be affected in both good and bad ways by climate change, Layton-Matthews says.

For example, earlier snow melt has so far increased production of eggs, and more of those eggs become goslings, because it has improved the availability of nest sites and food plants.

The researchers were more surprised to discover that the birds survived better when winters were mild in Scotland. If winters get milder in the future, which is expected due to global warming, the result can be that the overwintering populations continue to climb.

“Based on previous research I wasn’t expecting to find these pretty large, positive effects from winter temperatures,” she said, because the geese are fairly big and don’t seem as if the winter cold should be a problem for them.

Predators benefit, too

The benefit of the increased number of eggs and goslings due to warmer springs in Svalbard was also a benefit for the critters that prey on them, mainly Arctic foxes and polar bears. In fact, the healthier the goose population on Ny-Ålesund was, the more food there was for both of these animals, particularly for foxes.

Arctic fox numbers on Svalbard are partly linked to the number of reindeer, since they feed on the carcasses in winter and spring. In Svalbard as a whole, reindeer numbers have been increasing due to another effect of climate change: warmer, longer summers and “Arctic greening”.

However, as documented by Brage Bremset Hansen, one of the paper’s co-authors and Layton-Matthews’s supervisor, reindeer populations can also suffer in winters with rain-on-snow events, which cause their grazing areas to be covered with an impenetrable layer of ice. Such winters are bad news for the reindeer, but good news for foxes, because it boosts cub production in the spring.

And the more Arctic foxes there are, the more they can devastate goose numbers, Layton-Matthews said. “The foxes mainly feed on the goslings,” she said. “Which means that, even though gosling production increases with climate change, the net result is fewer adult geese recruited to the population.”

“It’s a real cascading effect,” she said.

Managing goose populations for the future

Still, the huge increase in overwintering birds in Scotland and elsewhere in Europe has led to calls from farmers to regulate the goose populations, Layton-Matthews said. The overwintering geese can reduce the amount of grass or wheat in a field a lot, Layton-Matthews said.

The trouble is, there’s little evidence that culling birds in Scotland will actually lead to reduced goose numbers, she said. Culling overwintering birds in Scotland means the birds that haven’t been culled will have more food to eat. The geese are also still colonizing new breeding areas in Svalbard which have come available due to the longer summer seasons, which open up new areas for an entire breeding cycle.

But if the production of young continues to be restricted by hungry foxes and polar bears, the net effect of all these changes may bring population numbers down, over time. Over the last two years in the study area, there has been more and more predation on the geese by polar bears, which is similar to trends observed elsewhere, Loonen said.

“That means any management of Arctic-breeding geese needs to factor climate change into the plan,” Layton-Matthews said.

“Future management plans to appease both the farming community and conservationists have to consider the potential for direct and indirect effects of climate change, all the way from the Arctic to Europe,” she said.

Reference:

Contrasting consequence of climate change for migratory geese: predation, density dependence and carryover effects offset benefits of high-arctic warming. Global Change Biology 2019. Kate Layton-Matthews, Brage Bremset Hansen, Vidar Grøtan, Eva Fuglei and Maarten JJE Loonen. DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14773S