This article was produced and financed by the University of South-Eastern Norway - read more

Norwegian researchers reject that Northern Norway is part of the Arctic

If you have visited the Northern Coast of Norway and thought you were in the Arctic, then you were mistaken.

This is according to Norwegian researchers who have mapped vegetation and temperature in Finnmark, the northernmost part of Norway.

For the tourist industry, the Arctic begins at the Arctic circle. The industry invites you to enjoy the midnight sun in summer and the play of the northern lights in winter, while farmers speak of ‘Arctic agriculture’ where the mild waters of the gulf stream warm the northwest coast of Norway.

But for ecologists, the Arctic begins where characteristic Arctic vegetation takes over and the ‘Arctic biome’ begins. The point of contention lies far to the north along the coast of Finnmark, which includes the northermost point in mainland Europe, the North Cape.

Biomes are broad geographical zones where the natural vegetation is similar due to the effects of climate and soil. Most of Norway is covered with the birch and conifer woods of the boreal zone, the northernmost forest biome. In the high north, the birchwoods of the northern boreal zone give way to the treeless heathlands of the Arctic.

Whether the northernmost parts of Norway belong to the Arctic or not has been a matter of debate for over fifty years.

In 2005, an international expert panel divided the Arctic biome into five subzones (A – E). They placed the heathlands of northern Finnmark in Arctic zone E, because these regions were considered to lie beyond the northern boundary of the birch forest and have an average July temperature under 10 °C.

Wrong use of treeline

In North America and Siberia, the boundary between the boreal forest and the Arctic zone is well-mapped, and in both these regions the treeline is several hundred kilometers north of the coast of Finnmark. Yet in spite of this, the importance given to the treeline has led researchers to include the heathlands on the north coast of Finnmark in the Arctic.

According to Professor emeritus Arvid Odland, however, it is the stormy waters of the Barents see that are responsible for the lack of trees in the far north of Norway.

«It is mostly due to lack of suitable growth sites, strong wind and sea-spray", he says.

"We have mapped air temperature, soil temperature, soil type, flora and vegetation. All these are clearly different from Arctic Siberia and North America. And in much of northern Finnmark the average temperature in July is over 10 °C, so temperature doesn’t hold as an argument either», Odland says.

Data from PhD project

Odland is a vegetational ecologist and he has travelled far and wide finding out why vegetation is as it is.

He was supervisor for Gauri Bandekar’s PhD at the University of South-Eastern Norway, which contradicts the accepted view that the northernmost coast of Finnmark is Arctic – even though the limit of birch woodlands lies to the south.

«On the contrary, the coastal regions in northern Finnmark have a great deal of ecological similarity with regions further south», says professor emeritus Arvid Odland.

Two summers of fieldwork

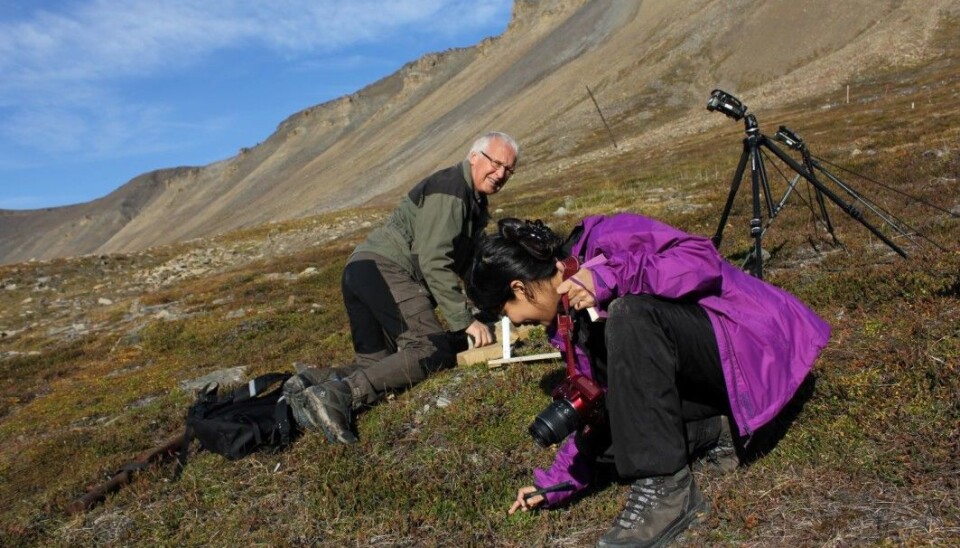

Odland and Gauri Bandekar travelled back-and-forth through Finnmark and Spitsbergen collecting field data for two summers. At every site they buried data loggers in the ground to record the variations in soil temperature. Staff of the Meteorological station helped to collect data on the inaccessible Arctic island of Bjørnøya.

«We have studied conditions in heathlands north and south of the treeline in Finnmark, and they were strikingly similar. In fact there was no real ecological difference between them. On the other hand, conditions were very different from those we found on Bjørnøya and Spitsbergen and clearly distinct from the description we have from North America and Siberia.», says Arvid Odland.

Boundary pushed south to the Arctic Circle

Now he hopes that the new findings will help to clarify the significance of the term ‘Arctic’. Different disciplines use different definitions of ‘Arctic’ and some push the boundary all the way to the Arctic Circle.

Odland considers that for biological sciences, such a boundary is meaningless and that the term must be based on thorough, multidisciplinary studies.

Gauri Bandekar presented her results and defended her PhD thesis in June 2018, and she is first author of a newly-published open-access article on the subject.

«Based on investigation of air and soil temperature, the soil characteristics and the absence of permafrost in Finnmark, we conclude that the regions both north and south of the treeline in Finnmark should be classified as boreal, not Arctic», states Bandekar.

References:

Gauri Bandekar et al: Bioclimatic gradients and soil property trends from northernmost mainland Norway to the Svalbard archipelago. Does the arctic biome extend into mainland Norway? PLOS One, 2020. Doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239183

Donald A. Walker mfl.: The Circumpolar Arctic vegetation map. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2005. Summary. Doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2005.tb02365.x

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no