THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY Nord University - read more

Animals on the seabed of the Arctic Ocean are barely affected by the seasons

In Arctic regions, living conditions change dramatically through the seasons. But on the ocean floor, life is little affected by whether it is summer or winter. This surprises researchers.

Bristle worms and mussels, crustaceans, and sea stars. They all belong to the group of macrobenthos, or ‘large bottom-dwelling animals’. They feed on what can be found in the sediments, on the bottom, or in the surrounding water.

These animals form an essential part of the ecosystem, both as food for other organisms and as 'factory workers' in the sediments.

“These bottom-dwelling animals are involved in the biogeochemical reactions on the ocean floor, as they modify the sediments and recycle what ends up at the bottom,” researcher Èric Jordà-Molina at Nord University says.

No winter hibernation at the bottom

The food these bottom-dwelling animals depend on comes primarily from organic material that sinks down from the water masses higher up.

This food supply is largely affected by the seasons, with a large bloom of phytoplankton in early spring, followed by rapid growth in zooplankton.

When winter darkness descends again up there, and ice spreads out, the zooplankton hibernates at greater depths, awaiting a new spring.

“The conditions in the Barents Sea change drastically through the seasons. We have the polar night, where the lack of light means no photosynthesis and thus no production of phytoplankton. Therefore, it was believed that winter here was a kind of 'sleeping' period for bottom-dwelling animal communities,” Jordà-Molina says.

But now it turns out that more is going on in the Arctic during the winter than previously thought. For the first time, researchers have studied seasonal changes in bottom-dwelling animal communities in the open sea in the High North.

“We want a better understanding of the rapid climate changes in the northern Barents Sea and the Arctic as a whole. In addition to looking at animal and plant communities, we are particularly interested in the timing and patterns of the processes that occur on the ocean floors,” Professor Henning Reiss at Nord University says.

Stable food supply in the sediments

The study has been part of the Nansen Legacy project, an interdisciplinary collaboration where researchers from Northern Norway have participated together with Akvaplan-niva.

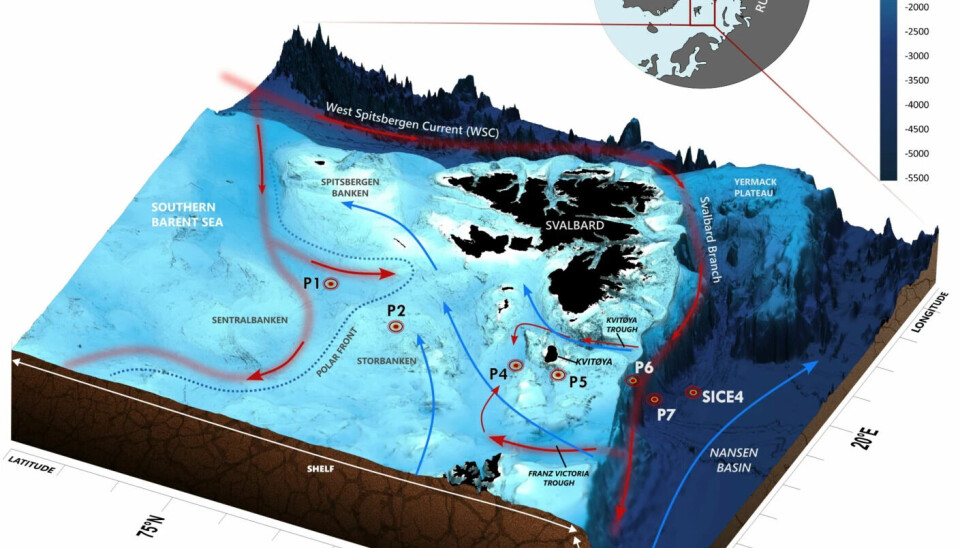

The researchers collected bottom samples from seven stations east of Svalbard in the months of August, December, March, and May.

The stations were chosen to look at animal communities on either side of the Polar Front, where warm Atlantic water meets cold Arctic water.

Furthermore, the researchers wanted to look at bottom-dwelling animal communities both on the continental shelf and down in the Nansen Basin.

The results surprised the researchers. They found little variation among the bottom-dwelling animals throughout the seasons, both in terms of species composition and the number of animals.

“Many bottom-dwelling animals reproduce in the form of larvae that float with the water masses. After a while, these will settle down on the bottom and begin to grow. In seasonal bottom-dwelling animal communities, one would occasionally be able to find larger amounts of such recruits, but that was not the case in our study,” Reiss says.

One reason may be that the sediments act as stable food stores during the nutrient-poor periods.

“It is still just a hypothesis. But due to the high degree of advection from nutrient-rich waters into the Barents Sea and the relatively high primary production in the area, coupled with low water temperatures, marine sediments could accumulate deposited organic matter and act as food ‘fridges’," Jordà-Molinasays.

This could give the possibility for recruits to feed on these reserves all-year long.

"This allows benthic organisms to reproduce at any time of the year, resulting in the lack of seasonality we observed," Jordà-Molina says.

Differences from shelf to basin

Although the animal communities at the different stations did not change throughout the seasons, there were still significant differences among the various stations.

“Many probably think that the ocean floor is the same everywhere, but there is great variation down there,” Jordà-Molina says.

Differences in environmental factors such as ice cover, depth, type of sediment, salinity, and temperature at the ocean floor have a major impact on the animal communities living on the bottom.

Just south of the Polar Front, the researchers found an animal community with high diversity, which could be due to higher productivity in the water masses above and greater access to food for the bottom-dwelling animals.

"In contrast, the animal communities down in the Nansen Basin were quite different, with more specialised and unique animal groups adapted to great depths and limited food conditions,” he says.

These are insights that can be significant when managing ocean resources, for example, when assessing mineral extraction in the Barents Sea.

A safety net

According to Jordà-Molina, this can also affect how – and perhaps when – bottom-dwelling animal communities are affected by climate changes. The Barents Sea is often called the 'Arctic hot spot' in a climate context, with faster temperature increases and effects on the environment than other places on Earth.

“Everything depends on what happens in the water column above. There are great differences in environmental conditions on either side of the polar front, and between shallow and deep water. These environmental conditions are expected to change in the coming years. We could get more Atlantic conditions and less Arctic environmental conditions. This will be able to affect the composition of bottom-dwelling animal communities in the long term,” Jordà-Molina says.

It's not just from the south that the Atlantic is 'creeping up' on the Arctic Ocean. Warmer water is also pressing in from the north into the Arctic habitats.

“That means the Arctic animal groups are being pressured from both sides,” Jordà-Molina says.

That the researchers did not find seasonal variations among the animals living down on the bottom here, however, may mean that the ecosystem has a buffer against major climate changes, according to the researcher.

“What we see is that these animal communities live independently of the seasonal variations in the water masses above them. It buys us time when it comes to changes in the Arctic environment. But it will not last forever, especially in a time where marine heatwaves and weakened ice cover occur increasingly frequently,” he says.

Reference:

Jordà-Molina et al. Lack of strong seasonality in macrobenthic communities from the northern Barents Sea shelf and Nansen Basin, Progress in Oceanography, vol. 219, 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.pocean.2023.103150

This content is paid for and presented by Nord University

This content is created by Nord University's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. Nord University is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from Nord University:

-

Kateryna's university has been bombed three times – but she's still teaching

-

5 things you didn't know about smart cities in the Arctic

-

AI sparked an idea that could improve road safety in Norway

-

These algae have been adapting for hundreds of millions of years

-

Could traces of bacteria in water combat salmon disease?

-

Bladderwrack in animal feed has the potential to reduce methane emissions