THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

Researcher: The people who painted these rock paintings were neither primitive nor naked

In a new exhibition, archaeologist Vibeke Viestad shows how we can use San people's dress and dress practices to interpret their world-renowned rock art in new ways.

For thousands of years, the San people painted fantastic and complex rock paintings that can be found scattered across southern Africa. But despite their early and advanced visual communication, the historical hunter-gatherer population has often been described as primitive Stone Age people.

“The San people were neither primitive nor naked. They used clothes, headdresses, bags, shoes, jewellery, tattoos, colours, and fragrance to create and maintain important social relationships between humans, between humans and animals, and between humans and other living beings,” Vibeke Viestad says.

She is a researcher at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo.

Viestad explains that dressing the body helped create harmonious relationships that were important for living in a world that consisted of many different types of social beings.

Has opened an exhibition in South Africa

Viestad’s exhibition is currently on display at the Origins Centre at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg.

The exhibition, which is based on her research, shows what dress practices has meant to San people.

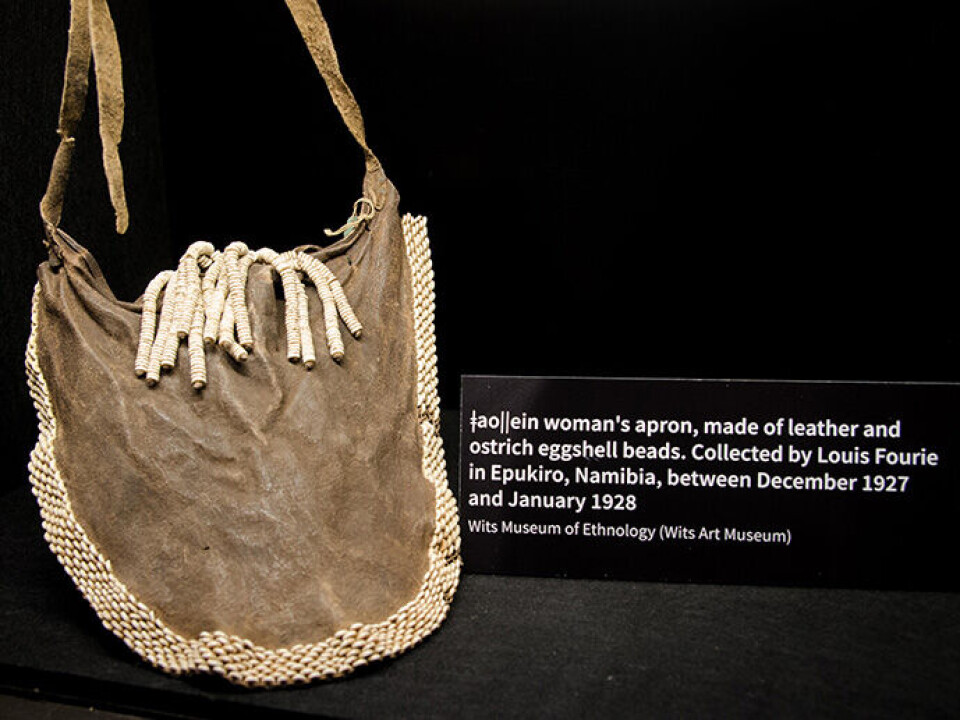

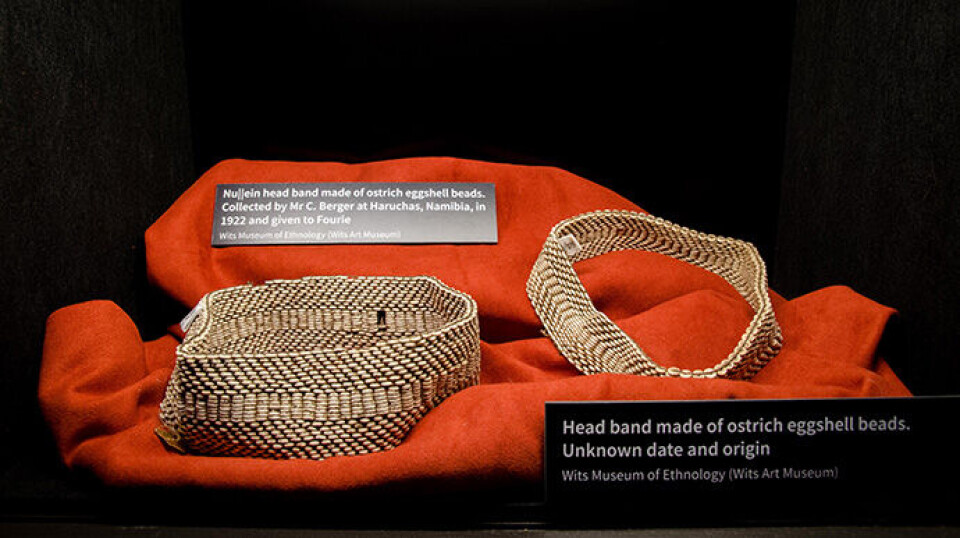

Through ethnographic artifacts, photographs, reproductions of rock art, and information texts, she explains how dress and personal ornamentation have been used intentionally, and that they have had different significance in different phases of San people’s lives.

It is here that the connection to rock art becomes evident: The knowledge of dress and dress practices can contribute to understanding parts of the rock art and its symbolism in new ways, according to Viestad.

The traditional interpretation of rock art is that it shows trance dance as a ritual practice, specifically the shaman's role and ability to move between different worlds during a trance.

“By emphasising what clothes, bags, and decoration of the body have meant in different situations, we can understand the symbolism and significance of rock art in other ways. It's likely that the art was created and used in many different contexts, not just to convey the shaman's perspective and experiences,” Viestad says.

Shows the man as a hunter, the woman as a gatherer

Viestad believes that many of the rock art images can be linked to rites of passage – and to the man's identity as a hunter and the woman's identity as a gatherer.

“We know that dressing in new or borrowed clothes and getting tattooed or painted has been an important part of rituals of transition from young to adult woman, from young boy to adult hunter or from novice to healer,” she says.

She shows examples of this in the exhibition. There are pictures of a group of people sitting close together covered in large skin cloaks, inside an enclosure that is secluded from the rest of the world.

Hunting bags have been painted over their heads, and in some of the pictures the distinction between animal and human is almost non-existing because the group can also be seen as the body of a large antelope.

Viestad explains that this represents the rite of passage for young hunters, and that the interpretation coincides with what has been described in written sources from the early 20th century.

“In some overhangs, several of these groups are painted, probably at different points in time. Perhaps they came back to perform the ritual, or to commemorate it,” Viestad says.

San people tattooed themselves before hunting to identify with the animal

Viestad's exhibition consists of six sections that follow the dressed body: leather clothes, bags, shoes, tattoos, beadwork, and tortoise shell boxes filled with fragrant herbs and plants.

Each section presents brief summaries of myths and stories where clothing and personal adornment play a crucial role. Viestad points out that myths can help explain actions, or associations that were important in the real world, and exemplifies: In the story of when animals became animals and humans became humans, all animals had marks and stripes branded into their fur.

The different characteristics set them apart as separate species, and people thought the patterns were so beautiful that they wanted to imitate the marks on their own bodies.

“In the real world, girls' tattoos were often directly compared to the beauty of the zebra. And for the hunter, it was important to ‘know’ or ‘feel’ the animal, identify with it, so that the animal he was hunting would not be frightened and disappear. He was able to achieve this by rubbing charred meat from previous hunts into parallel cuts on his arms, face, or back,” Viestad explains.

It was important to create harmonious relationships

Another myth tells the story about a young girl who rubs the powder of fragrant plants over the neck of the ‘Water’ to calm the creature and escape herself. Viestad believes that we can draw parallels from this story to young girls in the real world, because San-girls have used similar powder, collected in beautiful boxes made from tortoise shell.

“By powdering themselves and their loved ones, they became protected from the ‘angry water’ that falls with lightning and thunder. The hope was that it would rather be the soft rain that would come to penetrate the dry ground, making it fertile,” Viestad explains.

She further states that there are several examples in rock art that can be interpreted as decorated boxes made from tortoise shell.

“It seems that we can connect these boxes to the beliefs surrounding water and young girls' special relationship with water,” she says.

The importance of studying dress and dress practices

According to Viestad, studying the practice of dress and bodily expression is one of several keys to understanding cultural, ritual, and economic behaviour among people.

“In other fields of anthropological and archaeological research, clothing has often been taken seriously. When it comes to previous research on the San people, however, this has not been done to the same extent,” she says.

She believes that this is due to Western prejudices that San people were naked, or almost naked. Viestad believes that her research has contributed to a new perspective on this – and on the complex culture of the historical San people.

“The research has contributed to an increased knowledge about their lives and world views. In this way, I have also helped to expose some of the underlying prejudices that still prevail about San people and their culture,” she says.

The first exhibition of its kind

As far as Viestad knows, the exhibition is the first of its kind to present the importance of dress as cultural practice among the San people.

“The exhibition adds to the knowledge about southern Africa's indigenous hunter-gatherer population, who live as highly marginalised and vulnerable minorities in their respective countries today,” she says.

The Origins Centre is an important museum institution in terms of creating awareness with weekly visits from schools and students, a group Viestad believes is particularly important to reach with this type of knowledge.

“I want to contribute to increased understanding and tolerance between people. I think reaching young people is crucial to achieving this,” Viestad says.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family