This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

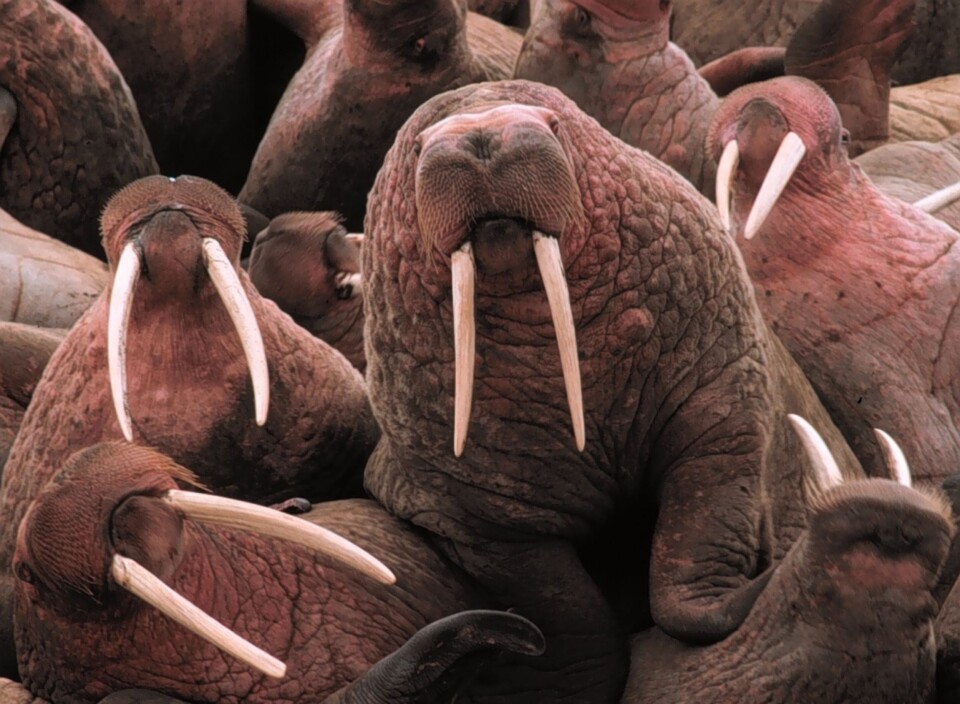

Vikings in Greenland traded exclusive walrus tusks to all of Europe – until there were no walrus left

Archaeological fragments of walrus skulls provide evidence of a widespread trade in ivory tusks across Europe during the Middle Ages. British and Norwegian researchers have now uncovered novel details about the impact of this intense trade: It may have driven the serial depletion of walruses in the High Arctic and led to the collapse of Norse Greenland.

In August 2018, a transdisciplinary team of Norwegian and British researchers found genetic evidence for the importance of walrus ivory trade as a driver for both the success and the decline of the Norse colony in Greenland. The Norse settlements were established by emigrants from Norway and Iceland in the 980s and lasted almost 500 years, until they finally disappeared between 1450 and 1500.

In 2018, the researchers had analysed ancient DNA (aDNA) from up to 1100 years old walrus ivory and skull fragments (originally left attached to traded tusks) found in European museums and collections. In medieval Europe, skulls served as packaging for the walrus ivory used for many art objects.

The same team has now included additional lines of evidence to reveal the intensity of this trade during the Middle Ages. With this evidence, the researchers are able to tell a comprehensive story about globalized trade and the way Norse settlers in Greenland depleted walrus populations.

Luxury products like the Lewis chessmen, made from walrus ivory, helped sustain the Norse settlements on Greenland for almost 500 years. (Photo: Andrew Dunn, Wikimedia Commons)

Valuable ivory from walrus

The Lewis chessmen are a famous example of how walrus ivory could be used to make wonderful art objects and artefacts. The chessmen were probably made in Trondheim shortly before 1200 CE and discovered in the 1830s on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Ivory from walrus tusks has been viewed as a less desirable substitute for elephant ivory in the Middle Ages, but the new study argues that its fashionability simply changed through time.

"Walrus ivory was very popular and valuable especially early in the Middle ages, particularly for use in Romanesque art. But later, in the 1200s, there was a shift in popularity from walrus to elephant tusks around the time when Gothic art developed”, explains the archaeologist Dr. James H. Barrett from the University of Cambridge.

Three roads to the full story

“We have used a combination of three separate methods in our efforts to uncover a detailed story about the trade in walrus products in medieval Europe. We combined archaeological analysis where we treated the skull portions as artefacts with analysis of aDNA extracted from the skulls. We also looked at stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, sulphur and hydrogen from defatted and purified bone collagen”, explains Dr. Barrett.

Before the project started, the researchers had reason to believe that walrus products could have come from different regions in the Arctic. An eastern source, from the Barents Sea region, was documented as early as the late 9th century CE, when the chieftain Ohthere (Ottar) of Hålogaland visited the court of King Alfred of Wessex in England.

“When we presented our last study in August 2018, we did not have the confidence to claim that Greenland was almost the sole source of walrus products for the European market. The reason is that the aDNA told us that some of the walrus products came from the western coast of Greenland, but we were not able to pinpoint where the rest came from”, explains researcher Sanne Boessenkool from the University of Oslo.

“That’s why we needed the extra information from analysing stable isotopes. The isotope signatures relate to the diet of the animals, and to their environment. So, if you have walruses living in the same place and eating the same food, they will have the same isotopic signature”, Barrett explains.

When the researchers added the results from the isotope analysis to the results from the other methods, they found that all but one of 19 medieval European finds of walrus skulls – analysed using both aDNA and isotopes – came from Greenland. A single skull, from the collections at the University Museum of Bergen, must have come from somewhere else.

A clear picture emerged

A modified and decorated walrus skull from medieval Bergen. (Photo: James H. Barrett, CC BY 4.0)

The combined results from the new study reveal fascinating insights into the hunting and trade of walrus by the Greenland Norse.

“We found that specific urban nodes redistributed the walrus ivory originally transported with the skulls. The earliest of these would appear to have been Dublin, Trondheim and Schleswig", Barrett explains.

The backdrop for this story is the population of Iceland in the second half of the ninth century, when Norse settlers migrated across the North Atlantic from Scandinavia. Later, as most Norwegian and Icelandic schoolchildren have learnt, explorers led by Erik the Red set out from Iceland and reached the southwest coast of Greenland in the 980s. The ensuing Norse settlements on Greenland lasted almost 500 years and consisted of emigrants from Norway and Iceland.

Hunting moves from Iceland to Greenland

“Our story starts where the Icelandic story ends. In Iceland, there are walrus finds in early Viking age sites. But later, they are described as a rarity. Previous research shows that the population of walruses in Iceland was hunted to depletion quite quickly after the Viking settlement”, Barrett explains.

When the Vikings could not hunt walrus on Iceland anymore, Greenland emerged as the new hunting ground.

“We had earlier discovered a genetic change, suggesting a major geographical shift from where walruses were obtained. The eureka moment for us came when we discovered that this genetic change coincided with a chronological sequence in the walrus skulls from Greenland – from male to female, and from large to smaller animals" says Researcher Bastiaan Star from the University of Oslo.

"Together, these findings suggest serial depletion as animals with smaller tusks, from sources further north along the western Greenlandic coast, had to be harvested to maintain the medieval trade in walrus ivory”, Barrett adds.

The Norse settlements Vesterbygd and Austerbygd were both on the west coast of Greenland, as starting points for hunting walrus further to the north. (Illustration: Finn Bjørklid, Wikimedia Commons)

Sequential manufacturing

The researchers did not rely only on ancient DNA and isotope analyses, because a trained archaeologist can uncover a lot of information just by looking at the artefacts. In this case, James Barrett was able to identify a surprisingly consistent way of removing the valuable rostrum or snout, that holds the tusks, from the rest of the skull.

“In most of the cases, the cutmarks are all from the same angle. They tell us that the hunter each time stood over a dead walrus laying on its left side and chopped off the rostrum with an axe or a large knife. Later, the tusks were modified and decorated. We found that almost all the skulls had been prepared in the same way, and the likely explanation is that the work was done by people living in the same settlements”, Barrett says.

The driving forces

There are many theories as to why the Norse settlements in Greenland collapsed after surviving for some 450–500 years. One theory says that the Norse settlements were undermined because there was no longer a demand for walrus ivory. Other theories for collapse of the colonies have included climate change – the “Little Ice Age”, a sustained period of lower temperatures, began in the 14th century – as well as unsustainable farming methods, conflict with the Inuit and even the Black Death.

The hypothesis about disappearing demand for walrus ivory appears inconsistent with the new evidence presented by British and Norwegian researchers.

“Instead, we are seeing an increased harvesting and depletion of the walrus population as time passes. The Norse Greenlanders still wanted to trade with Europe because they needed iron and wood and so on, so they had to continue hunting walrus in order to have something to trade with. However, the value of ivory from Greenland decreased both because of the competition from elephant ivory, and because of the reduced size of the animals they hunted in Greenland. If the unit price is lower, you need to produce more of it”, Barrett explains.

The conclusion is that the hunting of walruses increased because of lowered unit prices per tusk, instead of being reduced because nobody wanted walrus ivory anymore.

What does this tell us about the collapse of the Norse settlements in Greenland? Historians have told us that there were two Norse settlements in Greenland, and the western settlement – closest to the hunting grounds – disappeared as early as in the 1300s. The result was that the distance from the remaining settlement to the hunting grounds became larger, and increasingly larger when the hunters had to travel further and further to the north in order to find walruses.

“Imagine what a huge investment it must have been to row and sail in their small boats each summer, all the way from the Norse settlements, which were in south-west Greenland, to the hunting grounds. Discoveries of Norse artefacts in Inuit settlements show that the Norse settlers travelled as far as Ellesmere Island, which is very far to the north. I think it must have become pretty untenable to continue in this way. It is possible that this huge effort finally undermined the resilience of the Norse settlements in Greenland”, Barrett says.

Striking observations

Researcher Bastiaan Star finds it very striking that every observation the researchers have done during the investigation points toward the same story, which is described in detail in their new scientific paper.

“I was also struck by the fact that a lot of the stuff we make from plastics today, like small gaming pieces, dice, belt buckles and so on, could be made from ivory back then. The artisans in the Middle Ages were also able to make both beautiful pieces of high art and delightful folk art. Among my favourite examples are small figurines of Arctic animals that are carved from walrus teeth and are anatomically correct. One example from medieval Trondheim is of a walrus itself, complete with flippers and tusks. The interesting thing is that the carving could only have been done by someone who had seen a real walrus”, Star says.

A transdisciplinary project

In 2014, the Research Council of Norway funded an Oslo-led project named Tracking Viking-assisted Dispersal of Biodiversity using Ancient DNA. At approximately the same time, the Leverhulme Trust in the UK funded a Cambridge-led archaeology project on medieval Arctic trade called Northern Journeys. These projects later combined forces and have used aDNA to uncover new stories about the Viking Age.

In the new study, archaeologist James H. Barrett studied the skulls of walruses from museums. He also worked on the archaeological and stable isotope interpretations. The researchers Sanne Boessenkool and Bastiaan Star at the University of Oslo focused on sequencing and analysing the ancient DNA. The study of stable isotopes in the laboratory was performed by Catherine J. Kneale and Tamsin C. O’Connell at the University of Cambridge.

References:

J.H. Barrett et.al: «Ecological globalisation, serial depletion and the medieval trade of walrus rostra». doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106122

B. Star et.al: «Ancient DNA reveals the chronology of walrus ivory from Norse Greenland». Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 08 August 2018.

A.T. Gondek et.al: «A stainless-steel mortar, pestle and sleeve design for the efficient fragmentation of ancient bone». Biotechniques 2018, doi: 10.2144/btn-2018-0008

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no