This article was produced and financed by Norwegian centre for E-health research - read more

Diabetes patients may benefit from sharing health data

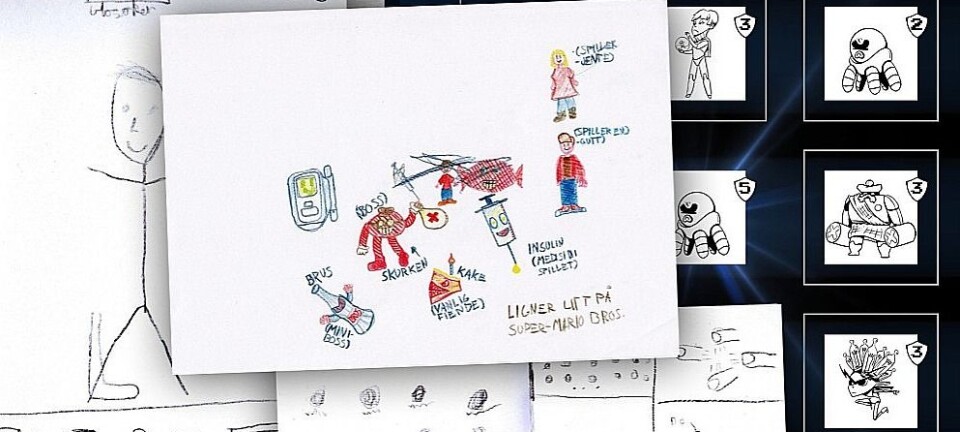

A new system that transfers health data from apps, smart insulin pens and sensors to health personnel may help diabetes patients receive more specific feedback and improved follow up.

The objective is to investigate how consultations of the future should ideally be, when patients collect more and more health information themselves. Users hope this will lead to fewer visits to the doctor.

Health technology allows patients to control their own daily lives more than ever before.

Whereas diabetes patients previously had to travel to a hospital or GP centre for a check-up, they can now record information in their current location with the aid of apps and other smart technological tools.

Self-collected and shared data can provide more information about a patient’s health status. When patients submit information from digital tools to health personnel, the information can provide a better foundation for advising the patient.

“Examples of such tools are insulin pens with communication, smart watches and armbands such as Fitbit, as well as apps that record physical activity. For example, the popular Runkeeper app,” says Alain Giordanengo from the Norwegian Centre for E-health Research. He recently published a scientific article on the subject.

Information from missing information

In a project financed by the Norwegian Research Council, and with supervisors and research colleagues, Giordanengo has developed a system that enables more relevant information to be extracted from shared data.

The data is systematised and could result in health personnel giving patients more detailed personalised advice and treatment. Indeed, the information that a patient shares says a lot about his or her health between consultations.

“The patient can simply feel better in that the technology detects, for example, the situations in which the patient has low blood sugar. The possibilities are there, but we must be realistic,” the researcher says.

Other research in this field has shown that much of the information about a patient’s health is hidden in the data diabetes patients collect themselves.

The advantage of technology is that patients can report their health status, regardless of where they are.

“They could be on a trip in the mountains and share data with a doctor via their mobile phone. The technology can also be used regardless of whether you are eight or eighty,” he stresses.

Hopefully fewer visits to the doctor

Diabetes patient, Hans-Henrik Hamrebø, is positive towards more direct sharing of health data and believes it could help patients.

“For example, I currently share data on glucose levels when I’´m having a check-up with the diabetes nurse. It takes a while, but not excessively long, for the nurse to upload the data. With direct sharing, I believe that more data covering a longer period of time will be available and provide the basis for better advice from health personnel,” says Hamrebø.

He believes that sharing data on, for example, activity, weight, volume of insulin and food results in fewer visits to the doctor and reduces the time spent on matters related to diabetes.

“For those of us who live about one hour’s drive from a city or town, three hours are soon saved for each check-up. If more data is shared instead of attending hospital check-ups, I expect that doctors, nurses and patients will have more freedom,” he says.

Hamrebø believes that all this depends on the willingness of patients to share correct data.

“This is probably not for everyone, but personally I would appreciate such communication between the health service and the patient. It will require some personal effort, but I believe that those who are willing to do this will be greatly rewarded.

Data from diaries

Blood sugar levels exemplify what patients can report without having to travel to a GP centre. Other examples are what they eat, medication and the type of physical exercise they do.

They can add details about what they eat/drink and how much they exercise, where they are in the their menstrual cycle, their stress level and how many calories they consume.

They can record when they inject their insulin and what mood they are in.

When combined, the data can provide considerable information about the clinical picture and whether it has changed since the last consultation. For example, whether the patient has better blood sugar values than earlier.

“As such, health personnel have the opportunity to give the patient better advice by looking at and suggesting changes in the patient’s daily life,” says Alain Giordanengo, IT Researcher.

Among other things, the research team will investigate whether closer collaboration between patients and health personnel can increase motivation for personal coping. Hopefully, self-reporting will help patients obtain a better understanding of how the various factors affect their diabetes, as this can vary from person-to-person.

“The objective of the system is that it will lead to a good reciprocity ring, where patients recognise the advantages of collecting and sharing data with health personnel - and health personnel see the resulting possibilities for more personalised follow up,” says Giordanengo.

Time-consuming for doctors

Giordanengo believes that the clinical and self-reporting parts are in many ways two different worlds. If you get them to talk together, it could be good.

Clinicians today mainly have access to information from what they analyse at the lab and what patients say.

Now, however, they can also access data patients share with them. The biggest problem is that it is time-consuming for doctors to go through the high volume of information in order to personalise treatment.

“GPs may not have time to prepare themselves properly. They have too much to do and sorting data for each patient will be an additional task for them. An app does not work alone. It’s essential to look at it in terms of how the collected data can be used in the simplest and best possible way,” he says.

Multiple users

Another problem is that doctors cannot always trust the technology, as they have not had time to learn it, and the third problem is that patients can manipulate the technology and ‘embellish the truth’ about what they are reporting.

“They may forget to record data or submit erroneous reports, or choose not to tell the doctor the truth,” says the researcher.

The researcher emphasises that the technology can also be transferred to other diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), overweightness and heart disease. However, this will not be possible in the foreseeable future.

Giordanengo and the team are now going to implement a study to test the system in hospitals and with GPs.

“Gradually, it could be implemented everywhere, but further testing must be done first. At best, it could be ready for rollout in 18 months time,” he says.