This article was produced and financed by NINA - Norwegian Institute for Nature Research

Seabirds are contaminated more by food than microplastics

Microplastics are not a significant source of environmental pollutants in fulmars. Seabirds ingest most of these pollutants through food.

Millions of tons of plastic float around in the world's oceans, most of it as microplastics. Waves, wind, and weather wear down the waste material until it is reduced to microscopic particles that remain in the sea for a long time.

It is not unusual for these microplastics to end up in the stomachs of marine organisms, where it can do great harm.

An additional cause of concern is the environmental pollutants linked to plastic, because although not all plastics contain hazardous substances, plastic has the ability to bind to fat-soluble organic pollutants from the environment and therefore reflects the concentration of environmental pollutants in the sea.

The fulmar - an indicator of plastic pollution

Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) belong to the order Procellariformes (“tubenoses”), a group of long-ranging seabirds that spend most of their time on the open sea, only seeking land during the breeding season. They feed on fish, crustaceans and other food in surface waters, and can thus easily confuse waste with food.

Studies have shown that most fulmars have plastic in their digestive systems, and the amount of plastics in fulmars is regarded as a representative indicator of ocean littering.

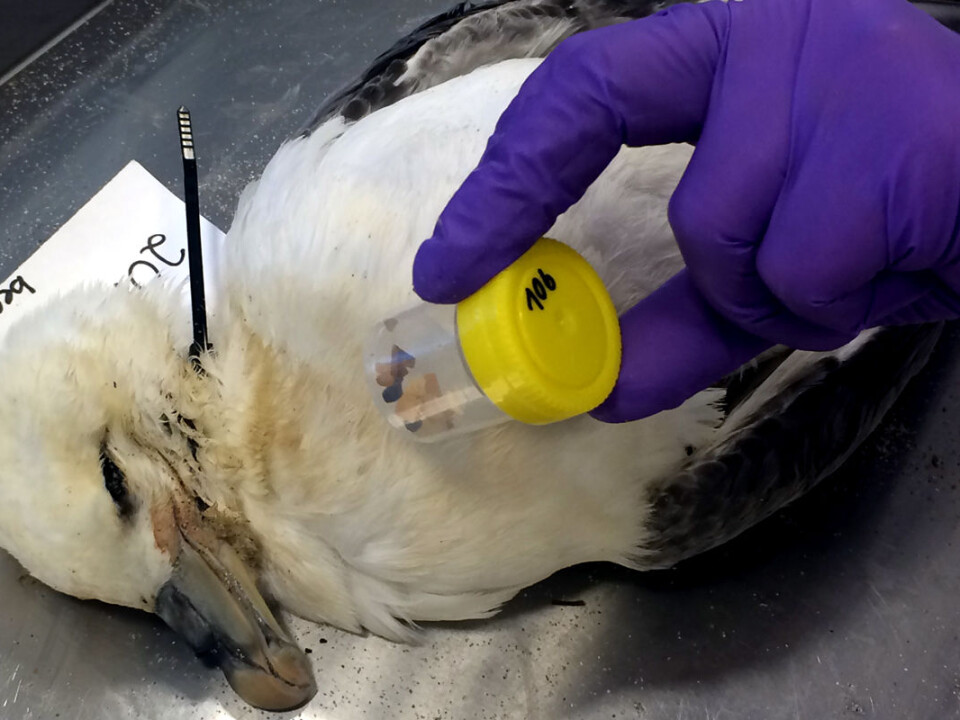

"Microplastics may remain in the bird’s stomach for weeks and months. We wanted to examine the extent to which environmental contaminants from plastic are absorbed by the birds' tissues," says Dorte Herzke, senior scientist and section leader at NILU - Norwegian Institute for Air Research.

Along with Tycho Anker-Nilssen, senior scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), she has led the project in which an interdisciplinary group of researchers from Norway and the Netherlands have investigated the relationship between the amount of plastic and environmental contaminants found in fulmars.

To the researchers' surprise, they found no correlation.

Environmental pollutants derives mainly from food

The researchers looked at a total of 75 fulmars, and compared the amount of environmental contaminants in plastic from the birds’ stomachs with the levels of the same substances in the birds' livers and muscular tissues.

"We found no significant differences in the pollutant concentrations in birds that had eaten a lot of plastic, compared to birds that had less plastic in their stomachs. Plastic is apparently not a major source of environmental pollutants in these birds," Herzke concludes.

On the other hand, the study shows that the environmental pollutant levels found in the fulmars most likely reflects the level of pollutants in their prey.

"Contrary to what we had expected, we found that the plastic does not release environmental pollutants to the fulmar’s stomach to a big extent. What happens to a much larger degree is that the plastic actually absorbs such contaminants from food the bird has eaten, and thus reflects the pollutant levels in the prey," Herzke explains.

"This study also shows that it is not sufficient to look at either plastic pieces from bird stomachs, or to just examine the organs of birds with plastic in their stomachs. To get the full picture, it must be seen in context. We are the first to do that in Norway."

Good news

Since seabirds are top predators, they ingest environmental pollutants from all stages of the food chain. High contaminant levels could have a number of negative effects on seabirds, and among other things lead to hormonal disturbances and thinner eggshells.

"That the plastic does not increase the birds' pollutant load is obviously good news in an otherwise bleak reality for most of our seabirds," Tycho Anker-Nilssen adds.

But the scientists are far from acquitting plastic.

"We cannot exclude the possibility that plastic may transfer some environmental pollutants to the birds. But, now we know that it does so to a far lesser degree than the fulmars’ prey," says Anker-Nilssen. In addition, the plastic takes up space in the stomach, and may thus cause the birds to starve to death.

Although this study was directed specifically towards seabirds, the scientists believe that the results may have relevance for other vertebrates.

This is the first time this kind of study has been done in Norway, and the results were presented in a scientific article in Environmental Science & Technology at Christmastime last year.

The study has already received much attention worldwide.

-----------------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no