This article was produced and financed by Institute of Marine Research

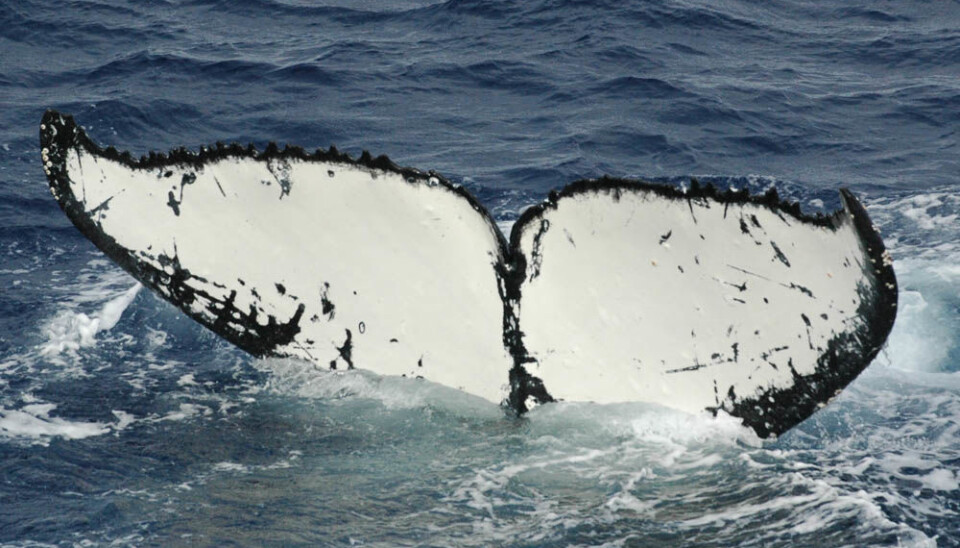

Humpback whales fuel up for a long trip

During the summer, humpback whales eat as much food as possible so that they're able to travel almost 8,000 kilometers to the Caribbean, and back again.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In recent years, some humpback whales have done their final fuelling up very close to the Norwegian coast.

There they have been spotted by many members of the public, people in kayaks and people on land have reported coming into close contact with these giant marine mammals.

Scientist Nils Øien of The Institute of Marine Research explains that herring tempt the humpback whales into the fjords.

“Eating these herring is the final ‘top-up’ for the humpback whales before setting out on their long migration to their overwintering areas in the Caribbean. When the herring come in as close to the coast as they have done for the past two years, the humpback whales follow them.”

Tagging experiments have revealed that humpback whales follow the herring south-west along the Vesterålen archipelago and on south as far as Lofotodden in Northern Norway.

A ceaseless hunt for food

A humpback whale population that numbers around 1,000 individuals spends the summer in the Barents and Norwegian seas.

The whales make use of the whole area. Early in spring, they enter the Norwegian Sea from the south, and many individuals can be found close to the coast of northern Norway. Later in the season, they head up to the area around the island of Bjørnøya. As summer draws to an end, the whales head north-east, where they feed on the big capelin in the area north and east of Hopen.

Throughout the summer, humpback whales are systematic and tireless in their hunt for food. During the feeding season, they probably eat up to five percent of their own weight each day. Humpback whales can weigh up to 30 tonnes, and reach a length of 12-15 metres.

Calves learn the route from their mothers

The whales migrate fairly directly from their feeding grounds to their overwintering areas, and the trip to and from the Caribbean takes around three months each way.

On average, the whales reach the Caribbean at the turn of the month February/March. Once there, the whales have two things on their agendas: calving and mating. There are probably evolutionary reasons why humpback whales give birth to their young exactly here: the water in the tropics is warm and shallow, and fewer predators threaten the calves.

Females with calves stay in the tropics until the calf is old enough to manage the trip to the feeding grounds. The calf learns the migration route to and from the feeding grounds from its mother, and faithfully follows this route for the rest of its life.

Whales head off the beaten track

The humpback whale population in the Barents Sea has been relatively stable for many years. Recently, humpback whales have also started appearing along the whole Norwegian coast. They have also been observed along the Dutch and Belgian coasts. In 2008, one humpback whale even went into the Baltic Sea, which had previously only been observed a couple of times over the past century.

“We don’t know why the humpback whales are heading off the beaten track. Often these trips end up with the whales becoming beached,” says Nils Øien.