An article from Oslo University Hospital

Machines will be able to diagnose cancer

Norwegian researchers are working on the automation of the work being done by medical specialists today.

"More Patients will get more accurate treatment, says project manager," Prof. Håvard E. Danielsen.

When a doctor suspects cancer somewhere in the body of a patient, he or she takes a sample of the tissue in order to provide an answer. But tissue samples may remain on hold for up to two months in Norway due to the lack of medical specialists who can make a cancer diagnosis. Most health systems in the world are in the same situation.

A new research project called DoMore! at the Oslo University Hospital aims to automate the task.

So far, 7,000 patients and 20,000 tissue samples are included in the project. Initially, the goal is to automate the diagnosis of prostate-, colon- and lung cancer.

Varying cancer diagnoses

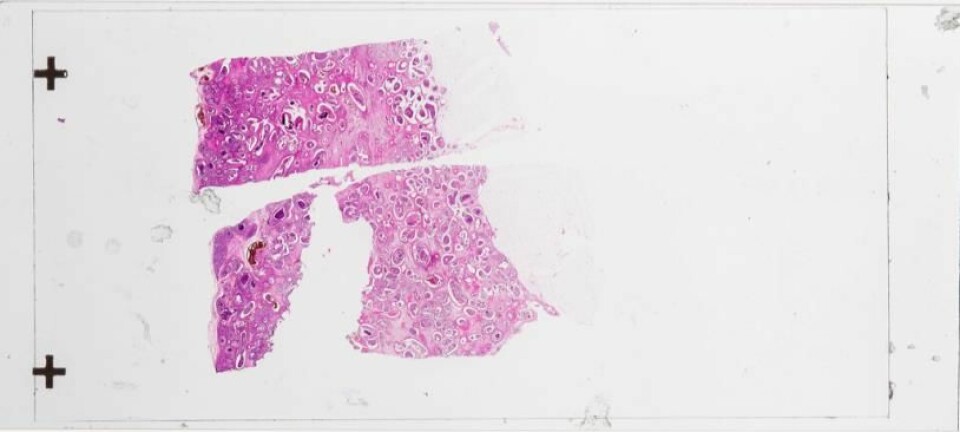

Physician specialists who make cancer diagnoses today are mainly pathologists, who work with tissue specimens, examining them with the help of tools such as microscopes. But pathology is also a subjective science, according to Håvard E. Danielsen, professor in genetics and computer science, who heads the DoMore! research project.

"When we compare the results, we can see that various pathologists make different conclusions on the same sample. One pathologist can also make different conclusions about a single sample assessed on separate occasions."

Danielsen underlines that major mistakes do not generally happen when it comes to the actual cancer diagnosis - the question of whether it is cancer or not. In these cases, the conclusions rarely prove to be wrong.

However, more errors are made when pathologists assess how serious the cancer is and the development of the actual disease, says Danielsen.

"These assessments are only correct in about 60 percent of cases, which means that there is an enormous potential for improvement," he adds.

From human to machine

Danielsen's research group at the Institute for Cancer Genetics and Informatics aims to ensure that a new digital system will be ready by 2021.

This system will not only be able to answer whether cancer is present in the tissue or not, but also indicate how the cancer might develop in the future.

In the same way that meteorologists use large amounts of information to calculate what kind of weather we can expect, this new system could predict a likely outcome for a given cancer.

Today, doctors are making these assessments and their conclusion determines which treatment the patient receives.

The goal of the new system is to make more accurate evaluations by using large amounts of data.

Pathologists fear outsourcing

Inger Nina Farstad works as a senior consultant and professor at the Oslo University’s Department of Pathology. Farstad, who is involved in the digitalization of pathology at both a regional and a national level, describes the development as a paradigm shift in the field of pathology.

According to Farstad, pathologists mainly worry about three things: that the technology will not fulfill its promises, how they will physically complete their work, and the perils of becoming outsourced.

"There is a fear that the tasks will be outsourced remotely in the future, for example in India," she says.

Farstad believes the problem is not that the pathologists make the wrong diagnosis, but rather that it may not be precise enough at times. Furthermore, it would be too time-consuming to reach a higher degree of precision.

"Therefore I see a greater risk in automation resulting in requirements for pathologists having to work even faster, rather than the risk of losing their job," she says.

Farstad prefers, however, to focus on the positive aspects of the development.

"Once processes are transferred over to computers, it will also increase opportunities for education and other types of knowledge sharing, which in turn will increase the level of knowledge. This is especially great from a patient perspective. The possibilities of sharing, also imply a new role for pathologists, who are used to being the experts who make the final diagnosis."

Hazardous cancer cells are not detected

One of the challenges of current cancer diagnoses is that they are based on samples from only a small portion of the tumor.

When a patient is checked for prostate cancer, for example, the sample taken by the doctor can be as small as one-thousandth of the tumor, despite that there can be great differences within one single tumor. Some parts of the tumor may contain cancer cells that cause little or no harm as long as the patient lives.

Other areas of the tumor may contain dangerous cancer cells that have the ability to proliferate and ultimately kill the patient. The assessment of the cancer’s severity thus depends on where in the tumor the samples are taken from. When there is already a lack of pathologists, introducing multiple samples per patient presents a challenge. If machines take over this job, it may be easier to map multiple samples per patient.

Surveillance instead of surgery

To be on the safe side, physicians today also treat tumors that are not necessarily dangerous. In other cases, patients do not get enough treatment before it is too late.

Both over- and under treatment of cancer is common, which is a major burden for patients and can be costly for society.

Prostate cancer is a good example of what is at stake. For many patients, the cancer develops so slowly that it is not considered to be dangerous. Because doctors do not know for sure which tumors this may apply to, many patients receive more treatment than they actually need.

With an automated system, more patients can receive more accurate treatment and society will save a lot of money, according to Danielsen.

"Active surveillance of a patient with prostate cancer instead of opting for surgery, means a cost reduction of 10,000 USD for each patient on average," says Danielsen.

The DoMore! project is a Lighthouse Project funded by the Norwegian Research Council.