An article from Norwegian SciTech News at NTNU

How the brain stores separate but similar events

The brain has an enormous capacity to store memories and to keep memories from getting mixed up in part because of how these memories are stored in the hippocampus, researchers from NTNU’s Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience have shown.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Since the time of the Greeks, people have used a special memory trick called the method of loci, which links memories to familiar places. You retrieve the memory by thinking of the place and calling up the associated memory.

Now researchers from NTNU’s Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience and Centre for Neural Computation have published new findings on how the brain is able to store many separate but similar events, which helps explain how this trick works. Their results have just been published in the 8 December issue of PNAS.

“We are extremely good at remembering places and we are very visual creatures,” says PhD candidate and first author of the paper Charlotte Alme.

Rats (and most likely humans) have a map for each individual place, which is why the method of loci works. Each place (or room in your house) is represented by a unique map or memory, and because we have so many different maps, we can remember many similar places without mixing them up.

Place cells in the hippocampus

The brain creates and stores memories in small networks of brain cells, with the memories of events and places stored in a structure called the hippocampus. Researchers have long wondered if there is an upper limit to our capacity to store memories. Nor do they fully understand how we are able to remember so many events without mixing up events that are very similar.

Alme and her colleagues from the Kavli Institute and from the Czech Republic and Italy explored these issues by testing the ability of rats to remember a number of distinct but similar locations.

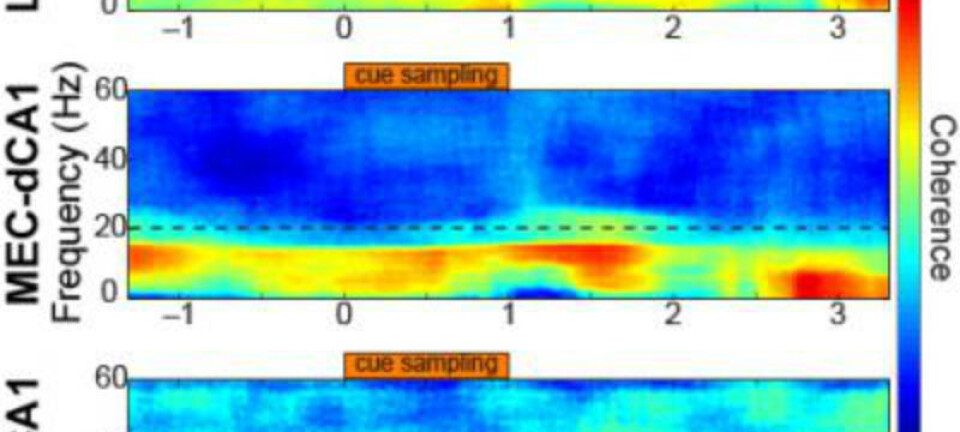

The researchers studied seven laboratory rats as they ran around in 11 distinct yet similar rooms over the course of two days. The freely running rats wandered around the rooms in pursuit of chocolate crumbs while researchers recorded brain activity in specific cells, called CA3 place cells, in the hippocampus. As their name suggests, place cells are neurons that fire in a specific place.

Separate and independent memories

The rooms were very alike, but the rats still managed to create a separate, independent memory, or a map for every environment, the researchers found.

The CA3 place cells the researchers recorded formed unique representations for each environment. The researchers also found that these unique representations or firing patterns were stored in the rats’ memories so that when the animal was introduced to one of the rooms a second time, the spatial map from the rat’s first exposure to the room was reactivated.

“We investigated whether these memories overlapped across some rooms, but all of the memories were completely independent,” Alme said. “This indicates that the brain has an enormous capacity for storage. The ability to create a unique memory or map for every locale explains how we manage to distinguish between very similar memories and how the brain prevents us from mixing up events.”

NTNU Professor and 2014 Nobel Laureate May-Britt Moser, who is the corresponding author of the paper, mentioned the research in her Nobel Lecture on 7 December in Stockholm and said that the findings were important for understanding episodic memory, or memories that are formed from autobiographical experiences.

The publication is a contribution by Professor Moser to a special series of Inaugural Articles being published by the journal in honour of those elected to the academy in 2014. Professor Moser and her husband, colleague and fellow Nobel Laureate Edvard Moser, were both elected as Foreign Associates of the US National Academy of Sciences in April.