This article is produced and financed by the University of Oslo - read more

Philosophers aim to help resolve crisis in physics

Researcher Karen Crowther reckons critical thinking can assist with the hunt for the theory that can describe “everything”.

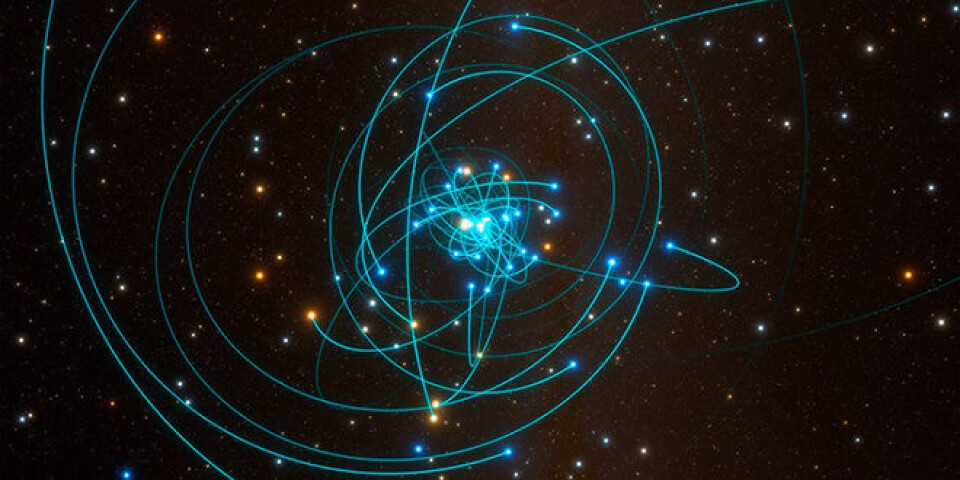

Despite a number of major advances in recent years, such as the first photo of a black hole in 2019 or the discovery of the Higgs boson particle in 2012, physicists are still searching intently for a revolutionary new theory.

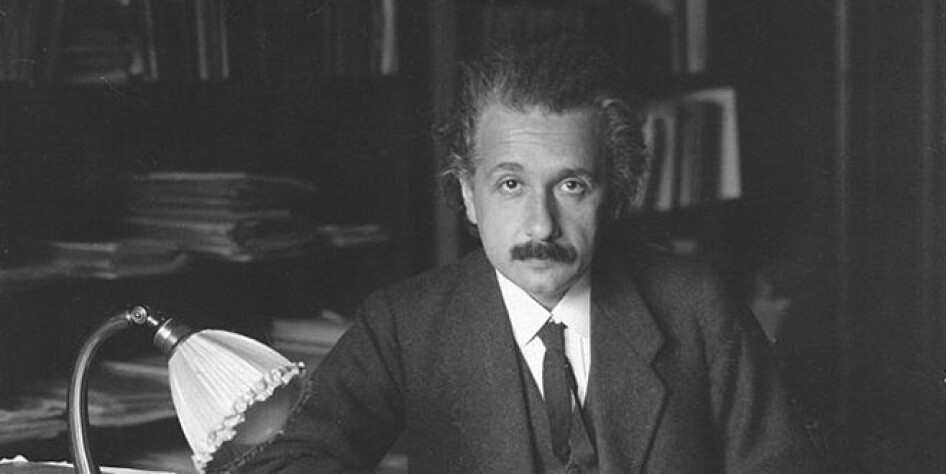

In 1915, Albert Einstein presented his general theory of relativity. Quantum physics was completed in the early 1970s with what is known as the Standard Model, which describes all elementary particles and interactions – with the exception of gravitational force.

“Physicists are now hunting for a theory that can combine the two and so describe everything. They are attempting to develop a theory of quantum gravity,” says Karen Crowther.

Originally from Australia, Crowther is a philosopher of science at the Centre for Philosophy and the Sciences at the University of Oslo, Norway. She has immersed herself in the philosophy of physics, and her ambition is to aid physicists with resolving their major crisis.

From physics to philosophy

It all began with formulae, X’s, square roots and laws.

“When I was a student of physics, I was captivated by harmonic equations and theories that could predict things correctly. But when I took a closer look, I realised that there are many questions left unanswered, and that many theories are incomplete. That bothered me.”

Luckily, an attentive teacher pointed Crowther in the direction of philosophy of science.

“In philosophy, there is more freedom to explore and ask questions — the most important focus is on critical thinking,” she says.

In most specialist fields, it is easy to get caught up in the rules of the field in question. Many researchers are consumed by the specific challenges that they face. Maybe they should take a step back and look at the issue with fresh eyes? This is where the philosophy of science comes in. Karen Crowther has chosen to approach the huge mystery of quantum gravity with critical eyes.

One theory for everything

“So in other words, we need a theory that can embrace what we have learned from both the theory of relativity and quantum physics. There are many ways in which we can search for this,” says Crowther.

We normally develop a theory in order to explain something that we are presented with, or else we come up with theories by means of experiments. When it comes to quantum gravity, the opposite is true.

“We talk about the inside of black holes, about the Big Bang or extremely small distances and periods. These are parameters that make no sense to us – we cannot see them or create data relating to them. So the question is: what would we do with a theory of this kind?”

Crowther believes that the crisis centres on this question. She has been researching quantum gravity theory for several years and is critical about detaching a new theory from reality.

“When the theories become so abstract, the question is more what the world would have looked like if the theory was true, rather than the opposite. The motivation for finding the quantum gravity theory is abstract and theoretical. For me, the crisis lies in the fact that what the theory should actually do has not been clarified,” she says.

When Einstein developed his theory of relativity, he was in the same situation as the physicists of today in many ways. He experienced discomfort on a theoretical level, according to Crowther.

“Einstein was also motivated by theory, and initially he had no data on which he could base his theory of relativity. It was not until later that the theory was tested and found to actually be true.”

Different approaches – the same problems

According to Crowther, many physicists are working persistently on devising that new theory; but she perceives a number of challenges on the horizon. That the researchers approach the challenge differently is one such challenge; that they do not talk to each other is another.

“They may either work with a top-down approach, or they work on the basis of a theory that already exists. The choice you make is dependent on your background,” she says.

If you work with high-energy particles and principles of quantum mechanics, you will probably end up working with string theory. If you start with the general theory of relativity, you will insist on using it and try to add quantum mechanics.

“Both of these are firmly established starting points, and no questions are asked if physicists choose to lean on either of these theories,” says Crowther.

“But it is also possible to work the other way round as well – adopt a bottom-up approach. This involves building up from fundamental structures and seeing whether what you find can match the theories.”

Whichever way you look at it, the physicists do not have the data they need to reach the finish line.

“Can new technology resolve this?”

“Technology will definitely help us get more accurate, but it will never be accurate enough. We will never get close to the extremely small distances inside black holes. Nor can we ever simulate or create the huge amount of energy required to move at the high speed necessary, not even in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.”

A new look at principles and methods

Crowther reckons that one solution might be to take a long step back and question the methods and principles used as a basis.

“Everyone agrees on the established principles, even though they normally use them in different ways. The question is whether this could limit the search for a new theory.”

According to Crowther, it is typical to assume that new theories must not break with the old ones. The old ones have worked, and so the new ones have to build on them. Many people also follow the virtue dictating that theories have to be elegant and harmonious.

“There are many ‘beautiful’ theories, in the sense that they are harmonious or symmetrical. This has been a feature of good theories in the past; so many people expect new theories to be just as beautiful. I think we have to discard such assumptions if we are to have the opportunity to come up with something completely new.”

Crowther is also critical of the notion that one should be able to use a new theory in fields beyond the one for which it was originally created.

“A theory is a tool, you have to use it for its intended purpose,” she concludes.

Take nothing for granted

Crowther works closely with physicists. She reckons that it is crucial for philosophers of science to be have close ties to researchers in the fields with which they work. She is of the opinion that the answer will be closer at hand for physicists thanks to her contribution.

“I try to help answer questions. Big questions, like what is going on in the universe and what is at the heart of time and space. But fundamental questions as well, the kind of thing that we take for granted when we try to understand reality.”

Reference:

Karen Crowther: Defining a crisis: the roles of principles in the search for a theory of quantum gravity. Synthese, 2018. Doi:10.1007/s11229-018-01970-4 Summary

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no