This article is produced and financed by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Place names describe Scandinavia in the Iron and Viking Ages

Every now and then, researchers are lucky enough to experience a Eureka moment — when a series of facts suddenly crystallize into a an entirely new pattern. That’s exactly what happened to Birgit Maixner from the NTNU University Museum when she began looking at artefacts and place names.

Maixner was recording metal detector finds from southeastern Norway when she had this “ah-ha” moment.

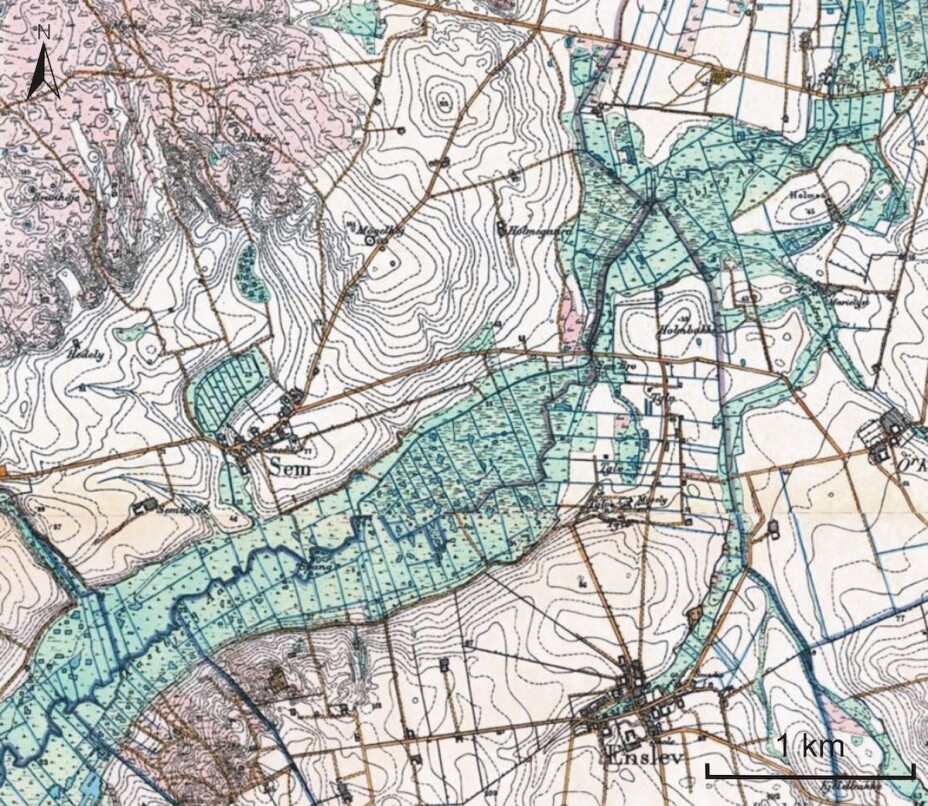

“The idea came to me as I was working with archaeological finds from three different places that had the same name: Sem in Hokksund, Sem in Tønsberg and Sem in Nøtterøy,” said Maixner, who is an associate professor at the museum’s Department of Archaeology and Cultural History.

Sem is a modernized variation of the old Norse place name Sæheimr.

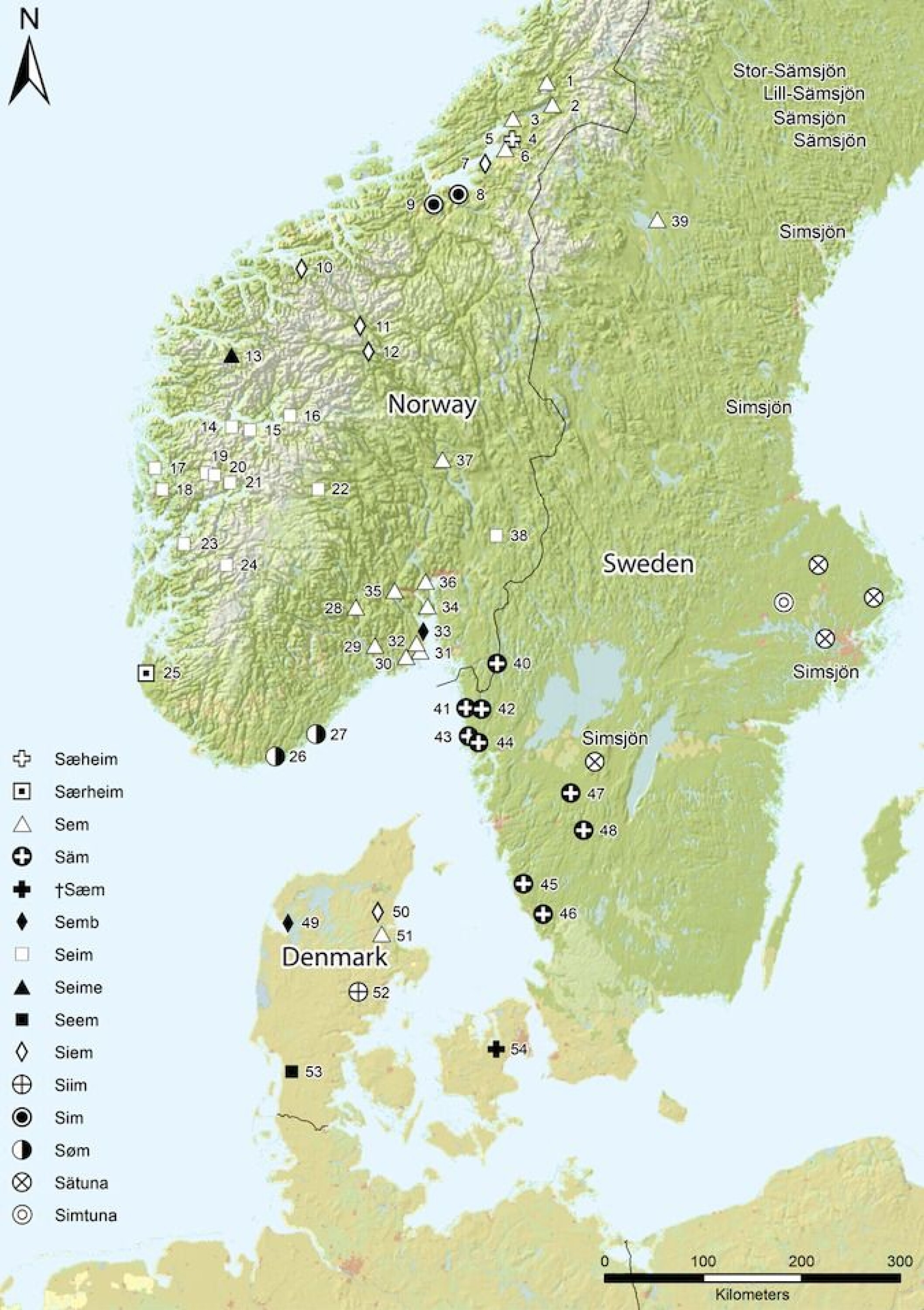

Fragments of this traditional place name can be found all over Scandinavia today: Særheim, Sæheim, Säm, Semb, Sem, Seim, Seime, Seem, Siem, Siim, Sim, Seam and Säm are all names derived from Sæheimr.

Traditionally, these names have been interpreted to mean simply “the settlement by the sea” – sæ = sea + -heim = settlement by.

However, when Maixner looked at the metal detector finds from the three different locations called Sem, she became convinced that the name contained much more than just a geographical description of the landscape.

“It wasn’t just the names that were similar, the metal detector finds were also of the same type. All the places had finds that indicated trade and production – for example coins, weights and production waste,” Maixner said.

“Suddenly it occurred to me that Sæheimr may have been a stereotypical place name referring to Iron Age maritime marketplaces. After that, I just had to do a tremendous amount of work to prove that my theory had something going for it,” Maixner said.

Close to centres of power

Linguists believe that place names ending in -heim or -hem are among the oldest in Scandinavia, and are primarily dated to the Roman Iron Age (ca. 0 AD to 400 AD) and the Migration Period (ca. 400-550 AD).

Researchers have known that the name Sæheimr has been linked to centres of power. The sagas tell of two Norwegian royal manors named Sæheimr. One was in Alver in western Norway – at the place today known as Seim – and the other in Sem in Tønsberg, in eastern Norway.

“Still, no one had done a more detailed survey of the places with names derived from Sæheimr to see if the name had a meaning beyond geography”, Maixner explains.

To test her theory, Maixner assembled Sæheimr variants from all over Scandinavia. She found 54 names in total – from Ribe in southern Denmark to Grong in central Norway. The name was most prevalent in Norway, and all the names – except one – are in use today. Maixner then checked to see if there were archaeological records from these places.

“I discovered that many Sæheimr sites were located near well-known pivotal locations from the Iron Age, or centres with political, administrative and religious functions,” Maixner said.

Similar topography

Land uplift and human impact have changed the landscape in Scandinavia a great deal over the last 2000 years. However, when Maixner adjusted for these changes, she discovered that the 54 sites once had a surprisingly similar topography.

“None of the places are located on the open coast. Instead, they are situated in sheltered positions near river systems of great strategic importance – often on a hill and often at the outlet of a lake. Had the name just referred to an arbitrary settlement by any sea, I would have expected the use of the name to be more widespread, with greater geographical variation,” Maixner says.

According to Maixner, this lends support to the theory she developed when she recorded metal detector finds from Sem, Sem and Sem.

“Everything suggests that Sæheimr has been a specific pan-Scandinavian concept that refers to a trading place accessible by boat. The distance between a Sæheimr site and its assumed centre is normally 1–5 km. The need for protection was great in the Iron Age, which is why the centre was usually located in a protected position in the hinterland,” Maixner says.

“We know that there have been many commonalities across Scandinavian society, for example religion and material culture. Still, considering the distances, it is very fascinating that people all over Scandinavia gave landing sites with market functions the same name, based on a set of criteria. By all accounts, this was a widely known concept. It shows that communication across Scandinavia was good, even in a society that for the most part didn’t write things down,” Maixner said.

Place names are like fossils

The archaeological material Maixner examined suggests that Sæheimr emerged as a place name early in the Iron Age, which matches the linguists’ dating of the name. It does not appear that new Sæheimr emerged after this time. Still, several places have nevertheless retained their function as a trading place throughout the Viking Age and, in part, even into the early Middle Ages.

“This dating is extremely exciting since just a few years ago we hardly knew of any trading places from the early Iron Age in Norway. Names like Kaupang, Lahelle and Laberg are used in association with trading places from the Viking Age and the Middle Ages, but we have been missing the same information for earlier time periods. This means the place name can be an important tool for archaeology,” Maixner says.

Maixner says she would like to test her theory through archaeological investigations.

“We have several promising candidates in central Norway that I would like to take a closer look at. It’s easy to imagine that Sem in Verdal and Sem by Leksdalsvatnet, for example, could have been trading places associated with the rich Iron Age society that once existed in this region,” she said.

She adds that this also demonstrates that there is a great untapped potential for cross-disciplinary research between archeology, linguistics and the study of place names.

“Unfortunately, there has been a dramatic drop in recent years in the number of academic environments studying place names, and just a few researchers remain in this field in Norway today. It’s a pity when you see how much information place names contain. In many ways they are like fossils in the landscape. They tell us stories about the past — if we know how to interpret them,” Maixner says.

Compelling results

“What Maixner has done here is interesting. She has studied whether it’s possible to find common archaeological features behind the creation of place names. It’s never been done in this way before, and the results are quite surprising,” says Peder Gammeltoft, from the University of Bergen.

Gammeltoft is Senior Academic Librarian and Scientific Manager of the Norwegian Language Collections at the university and has also studied place names in the Viking colonies.

“The use of the name Sæheimr can apparently be connected to a centre of power, without the name itself referring to power, hierarchy or the like,” Gammeltoft said.

This means that Maixner has found evidence that certain social functions in Iron Age society were named based on a non-explicit model, rather than the name directly referring to the site’s function, he said.

“This is very exciting. Still, we need to be aware that this is a theoretical reconstruction of the past. We cannot be entirely sure that this is exactly the way it was, but the results look compelling,” he said.

Reference:

Sæheimr: Just a Settlement by the Sea? Dating, Naming Motivation and Function of an Iron Age Maritime Place Name in Scandinavia, Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 2020