This article is produced and financed by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

The first battle for oil in Norway

The world’s richest man and the world’s largest oil company dominated the petroleum market in Norway long before landmark finds on the Norwegian continental shelf and the Norwegian oil fund.

Although it might seem like it, Norway’s oil history did not begin with the major Ekofisk discovery in 1969 by Phillips Petroleum Co. It didn’t even begin with the Balder discovery a couple of years earlier, or Norway’s claim to large areas in the North Sea in 1963.

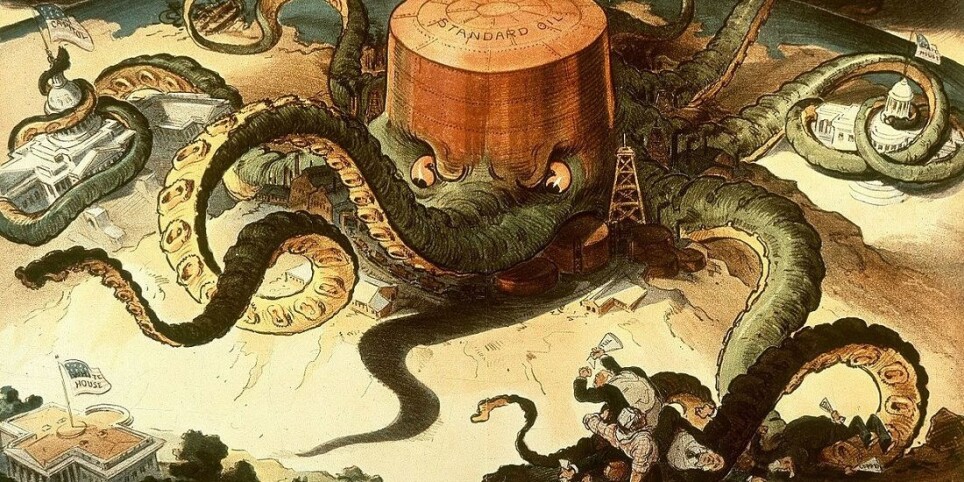

A better place to look for a kind of beginning is at the end of the 19th century. The story involves one of the richest men of all time, John D. Rockefeller, and his giant company Standard Oil.

It’s also the story of how governments in small countries struggle to fight economic giants.

Heavy-handed methods

“In the first phase starting in 1890, the Norwegian, Swedish and Danish oil markets were dominated by the large global oil company Standard Oil, which didn’t hold back from using rather heavy-handed tactics to control the market,” says Espen Storli a professor at NTNU’s Department of Modern History and Society.

This aspect of Norwegian and Scandinavian oil history has not been studied that much to date, but Storli and his colleague Pål Thonstad Sandvik address the period in an article in the Scandinavian Economic History Review.

“Standard Oil’s approach is a typical example of how large companies try to gain advantages and monopolies by leveraging their financial power and taking control of value chains,” Sandvik says.

World’s richest private individual

In terms of money, both Standard Oil and the company’s famous owner, John D. Rockefeller, had more than enough.

If you don’t include royals and dictators who ruled whole countries, Rockefeller stands out as perhaps the richest person in history. He became the first billionaire in the United States, at a time when an ordinary industrial worker had an annual salary of about US $500. Relatively speaking, Rockefeller was far richer than Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, the world’s richest living person today.

Ron Chernow, who wrote a biography about Rockefeller, described him like this:

“He could be extraordinarily violent when he wanted to force competitors to submit. But at the same time he did not exert this pressure casually, and where possible, preferred patience and argumentation rather than intimidation.”

Rockefeller’s wealth came largely from his oil company Standard Oil, which he helped start in 1870. Through ingenuity, cunning, acquisitions and a not-so-little use of muscle, the company became completely dominant in the national and global oil sector. Eventually, this applied to all parts of the value chain.

Market access

At the beginning of the last century, few European countries had known petroleum reserves. As a consequence, oil companies in Norway competed most for access to the sale of products like kerosene and petrol, and not for extraction rights or other parts of the value chain.

“Product sales were also where the oil companies collided most directly. The need for regulation quickly became clear to the authorities,” says Sandvik.

But this task was far from easy for inexperienced politicians and officials. Their opponent used varied tactics and had much more experience and money.

Danish company became a pawn

In Scandinavia, Standard Oil used the company Det Danske Petroleums Aktieselskab (DDPA) as a pawn. Standard Oil bought into DDPA as early as 1891, and later owned half of its stock.

In practice, DDPA became a subdivision of Standard Oil, because the management in Denmark had to consult with the American company in all important decisions.

The Danes already had a solid position in Scandinavia before Standard Oil came in, but only with American money did things really turn around. Sometimes the methods were ingenious.

For example, DDPA had long-term contracts with sellers of petroleum products. These sellers were not allowed to sell products from suppliers other than DDPA. If the sellers broke these contracts, they had to pay large fines, not to DDPA, but to local charities. This was probably a wise strategy, because protesting against a company that appeared to be running a charity was more difficult.

DDPA and Standard Oil eventually succeeded in taking over large parts of the market, but they never secured a complete monopoly. Actors such as the Europäische Petroleum Union and Pure Oil gave them solid competition at times, even if they were proportionally much smaller companies.

Most people worried

Standard Oil’s dominant position gradually became a concern for more than just the authorities and competitors.

“The debate about Standard Oil gradually grew, but it wasn’t easy for the authorities to do anything given the company’s power. For small countries with limited resources, it was difficult to respond to cartel activities and cooperation between companies that exploited their position in the oil market,” says Storli.

But the company wasn’t able to hold its position without Norwegian politicians being fully involved.

“Standard Oil’s grip on the Scandinavian oil market gradually weakened due to competing companies,” Sandvik says.

This was partly due to the fact that the company could not continue operating in the same way following a court decision in the USA.

Grew too big

Standard Oil grew too large, and in 1911 the Supreme Court of the United States had had enough. The court sought to dissolve the company because it had used illegal methods to gain a monopoly-like power over the US oil market. Standard Oil was then split into 34 different companies.

Standard Oil’s successors were also big in Scandinavia until 1939, if not as dominant as before. Some of the companies that stemmed from this split are still among the world’s largest, such as Amoco, ExxonMobil, Marathon and Chevron.

Rockefeller himself gradually withdrew from business life starting in 1896 and eventually concentrated mostly on philanthropic activities. He died in 1937, almost 98 years old.

Lingering effects today

The effects of the strong oil dominance at that time can be seen even today.

“The oil companies’ abuse of market power was exactly what Norwegian politicians wanted to avoid. This experience was important when Norway’s parliament passed strict competition legislation and comprehensive regulation of Norwegian natural resources such as hydropower, forests and minerals,” says Sandvik.

These regulations would come in handy a few decades later, when Norway itself proved to be sitting on large petroleum riches. Unlike many other countries, the country has largely managed to retain large parts of these riches, to a great extent because the Norwegian authorities already had extensive experience in regulating natural resources.

“Norwegian politicians and bureaucrats were well informed about the phenomenon of market power in the oil industry. This affected how they related to the large foreign oil companies in both the 1960s and 1970s,” Storli says.

“Of course, it’s always difficult to say where politicians and officials draw their perception of reality from, but it isn’t surprising that domestic experiences have been an important factor,” he says.

Reference:

Pål Thonstad Sandvik & Espen Storli: The quest for a non-competitive market: Standard oil, the international oil industry and the Scandinavian states, 1890–1939. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 2020.