This article was produced and financed by The Research Council of Norway

When hallucinatory voices suppress real ones

A brain mechanism in patients who hear inner voices prevents them from hearing real ones. A simple electronic application may help the patient learn to shift focus.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“The patient experiences the inner voices as 100 per cent real, just as if someone was standing next to him and speaking,” explains Professor Kenneth Hugdahl of the University of Bergen. “At the same time, he can’t hear voices of others actually present in the same room.”

Auditory hallucinations are one of the most common symptoms associated with schizophrenia.

Neural activity ceases

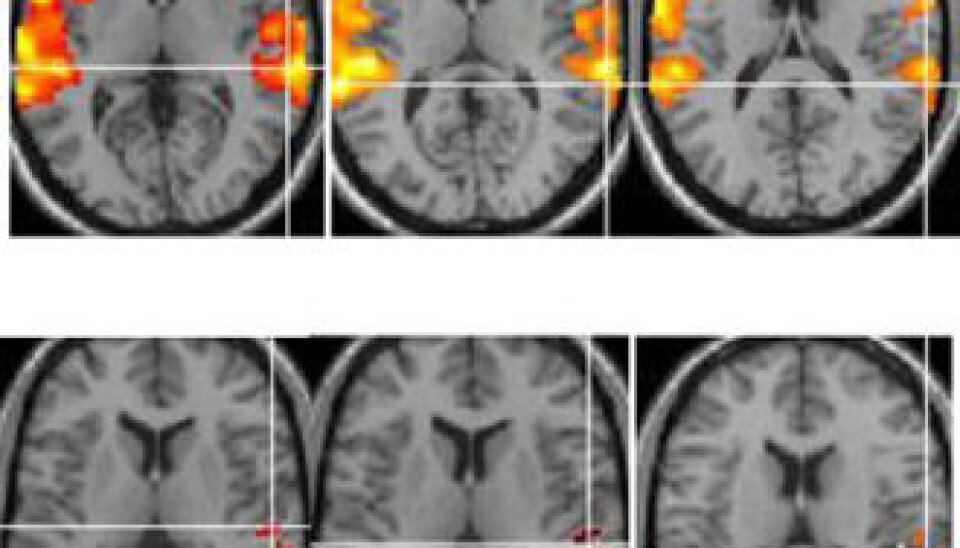

Hugdahl’s research group has made use of a variety of neuroimaging techniques, including functional magnetic resonance imaging technology (fMRI) to enable them quite literally to see what happens inside the brain when the inner voices make their presence known.

Images of patients’ brains reveal a spontaneous activation of neurons in a particular area of the brain – specifically the rear, upper region of the left temporal lobe. This is the area responsible for speech perception, and when healthy people hear speech it becomes activated. So what happens when patients with schizophrenia hear a real voice and a hallucinatory one at the same time?

“It would be natural to assume that neural activity would increase somewhat – even twofold. But quite the opposite takes place; we actually observed that the activity ceased altogether,” states Hugdahl.

Losing contact with the outside world

In order to learn more about what was happening, Hugdahl and his colleagues Kristiina Kompus and René Westerhausen carried out a meta-analysis of 23 studies. These studies focused either on spontaneous inner-voice triggered neural activation in subjects with schizophrenia or the stimulatory reaction prompted by actual sounds in both healthy and schizophrenic subjects.

They found that many researchers had observed either that a spontaneous activation of neurons occurs in patients hearing inner voices or that the patients’ perception of actual voices becomes suppressed when these are heard simultaneously with inner voices. No one had seen the connection between these findings.

“Previously, we thought these were two separate phenomena. But our analyses revealed that the one causes the other: when neurons become activated by inner voices it inhibits perception of outside speech. The neurons become ‘preoccupied’ and can’t ‘process’ voices from the outside,” explains Hugdahl.

“This may explain why schizophrenic patients close themselves off so completely and lose touch with the outside world when experiencing hallucinations,” he says.

Electronic app designed to improve impulse control

Hugdal and his colleagues made yet another discovery that may well help explain how the lives of these individuals become consumed by inner voices. It turns out that the frontal lobe in the brains of schizophrenia patients does not function exactly the way it should. As a result, these patients have a lesser degree of impulse control and are unable to filter out their inner voices.

“Every one of us hears inner voices or melodies from time to time. The difference between non-afflicted individuals and schizophrenia patients is that the former manage to tune these out better,” the professor points out.

If patients could learn to stifle inner noise it could have a huge impact on our ability to treat schizophrenia, he states. To this end, Hugdahl’s research group has developed an application that can be used on mobile phones and other simple electronic devices, to help patients improve their filters.

Wearing headphones, the patient is exposed to simple speech sounds with different sounds played in each ear. The task is to practice hearing the sound in one ear while blocking out sound in the other. The application has only been tested on two patients with schizophrenia so far. The response from these patients is promising, Hugdahl relates.

“The voices are still there, but the test subjects feel that they have control over the voices instead of the other way around. The patient feels it is a breakthrough since it means he can actively shift his focus from the inner voices over to the sounds coming from the outside,” the professor explains.

Translated by: Glenn Wells/Carol B. Eckmann