This article was produced and financed by University of Bergen

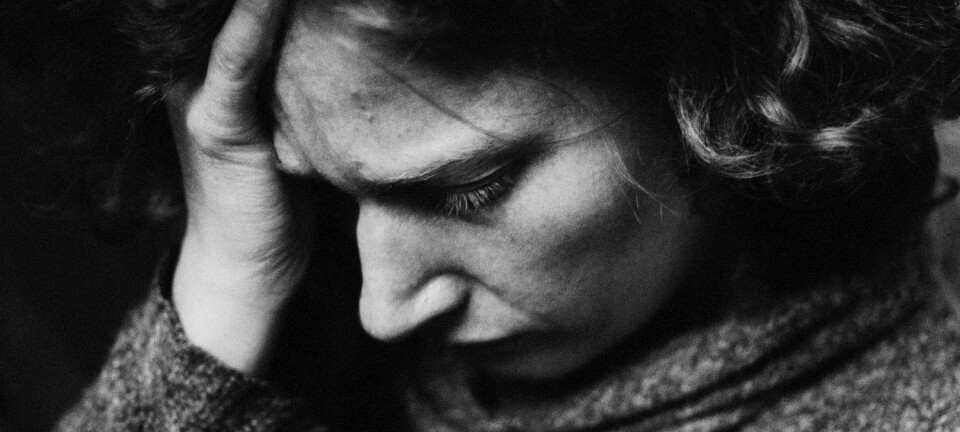

On the mental catwalk

When the diagnostic thresholds are lowered, being normal ends up being as unachievable as the supermodel on the catwalk, according to professor of philosophy.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In Norway, the diagnostic manual for mental disorders (ICD-10) is strongly influenced by the DSM system developed by the American Psychiatric Association. The DSM editions are criticised for constantly lowering the thresholds for qualifying for a psychiatric diagnosis.

When psychiatrists redefine what is normal and abnormal this is not contained in a closed session, but holds wider cultural significance. The steady downgrading of the diagnostic thresholds does something to how human beings view themselves.

"We are in the process of turning the disease into the norm and where the normal becomes the exception. If this continues, we will eventually see that what we deem normal is put on what I call the mental catwalk," says Professor Lars Fredrik Svendsen at the University of Bergen’s (UiB) Department of Philosophy.

Biological power diagnosis

Just like the super models on the catwalk we risk seeing the normal as an aberration and it becomes something that lies beyond what’s humanly achievable, the philosophy professor suggests.

In practise this may imply that more people deviate from the norm and that more people will want to submit to medical treatment simply to approach some semblance of normality. Not unlike the way perfect bodies are being photo-shopped in lifestyle magazines.

"The diagnostic manuals hold a lot of sway, creating biologically determined diagnoses," Svendsen believes. "These manuals shape our lives in unprecedented ways."

Paradoxically we are becoming less tolerant of deviations at the same time as many more of us are deemed to be deviants.

"I believe there is good reason to discuss whether the criteria we use on what is normal and abnormal are reasonable at any given time," he notes.

Only slightly less abnormal

DSM-5, which is scheduled for publication later in 2013, is not just offering new diagnoses, but also sub threshold mental disorders. If a patient does reach the required criteria for a proper diagnosis, he or she will not necessarily fall below the pathological threshold. Instead he or she will be considered only slightly less abnormal.

A proposal that is hotly debated is the diagnosis known as 'psychosis risk syndrome'. The idea behind this diagnosis is to identify people who may be developing schizophrenia early on, so that the patient may receive treatment at a younger age.

The public debate on issues surrounding diagnostic manuals has become so intense that even Allen Frances, chair of DSM-5’s precursor DSM-IV's task force, in 2009 stated that this could easily turn into a 'bonanza for the pharmaceutical industry but at a huge cost to the new false positive patients caught in the excessively wide DSM-5 net.'

Not fit for normal life

Many critics of the diagnostic manuals believe that a number of general human features have become pathologised over the last few years. For example, in a proposal submitted to DSM-5 it is argued that post-death grief qualifies as an unconditional symptom of depression.

"It has become far too easy to be diagnosed for depression," Svendsen argues.

"One has to remember that depression is classified as one of our most severe diseases by the World Health Organization (WHO) and is considered as debilitating as blindness or Down’s syndrome."

According to Svendsen, there has been a gradual shift away from seeing ourselves as relatively resourceful people with an ability to handle life to being chronically vulnerable.

"We are in the process of creating people who are unfit to live life", Svendsen suggests.

A strong identity

Svendsen believes that we should generally be cautious in making a diagnosis, and that a diagnosis is a label that creates an image of who and what you are.

"There is the danger that your diagnosis becomes your identity when the thresholds are lowered. But what we should keep in mind is that the diagnosis says nothing about the positive beliefs and resources inherent in a human being," says Lars Fredrik Svendsen.

Translated by: Sverre Ole Drønen