An article from Norwegian School of Economics (NHH)

Media's power over science

The media shape the public's views about controversial scientific issues through the language they use to frame these issues.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

For most people, their news about research and science come filtered through the media. The manner in which the issues are presented and framed by journalists is therefore of major significance to how we view them.

Professor Trine Dahl of the Department of Professional and Intercultural Communication at NHH - Norwegian School of Economics has looked at how contested scientific issues, for example, research into climate change and climate initiatives, are framed in different ways through the language used, thereby giving the reader completely different impressions.

Always an angle

Professor Dahl took the title, lead and statements from sources in six news articles from different publications, all reporting the same research news from the field of climate science. As a linguist, she looked at the expressions that are used and how these are utilised to create meaning in the text.

The news that forms the basis of the articles is an experiment in which the sea is fertilized with iron to bind and sink carbon to the sea floor. The research group was able to demonstrate that this in fact occurred. The experiment goes under the label of geo-engineering, or climate engineering, which is an extremely controversial approach to solving climate-related challenges.

“My linguistic study can be viewed as a type of natural experiment, since the underlying news story is the same for all of the news articles I looked at. I thereby compare multiple representations of an issue that could, in principle, have been written in the same manner, but which, as it turns out, was presented differently. In this way, the framing, as the phenomenon is known, clearly presents itself,” Dahl says.

Loaded expressions

The professor notes that framing an issue or giving it an angle is something we do all the time and is difficult to avoid.

If, for example, you ask two children to recount an event or experience they have both witnessed, they will often bring up completely different things, Professor Dahl says. Since no one who conveys a message is completely neutral, it is important to be able to analyse what one reads, particularly for major and important issues for which there are many viewpoints.

In journalism relating to research news, the angle is shaped through what the writer chooses to make visible, and the descriptive expressions this is linked to. Professor Dahl refers to the description of the duration of the reported climate initiative as a clear example of this.

“For centuries”?

The scientific article that the news texts are based on optimistically reports that the initiative can store carbon “for timescales of centuries in ocean bottom water and for longer in the sediments.”

In line with this, the British BBC writes in its introduction that the initiative “can lock carbon away for centuries.” However, in the popular science magazine, Scientific American, the journalist writes that the carbon can only be kept in the deep ocean “for a few centuries at best”. For its part, The Guardian cites a source that even more critically states that the initiative will only have an effect "for decades to centuries".

Most of the journalists approached the lead author of the scientific article, Dr Smetacek, and obtained quotes from him. Several of them allowed Dr Smetacek to enthusiastically tell them about the scientific process.

In The New York Times, he says “we saw the stocks start to sink, they went down very fast. I was very excited.”

Quotes and framing

However, in Scientific American, attention is drawn to the risks of the experiment, and Dr Smetacek is quoted as saying that “In fact, [the process] could backfire by producing toxic algal blooms or oxygen-depleted “dead zones”. […] At present, scientists have no way to ensure [the desired outcome]. [The process] cannot be controlled at this stage.”

“In this way, the journalists engage in framing because they choose to cite different quotes from the same source. Journalists must of course report what the source actually says, however, they can select what quotes will be included in the article and those that will be left out. The journalist also chooses what the source will be asked about.”

Dahl notes that no representation is neutral and that each person conveying the news will always have a background that can shape their angle. Some media sources have also taken a clear position on issues.

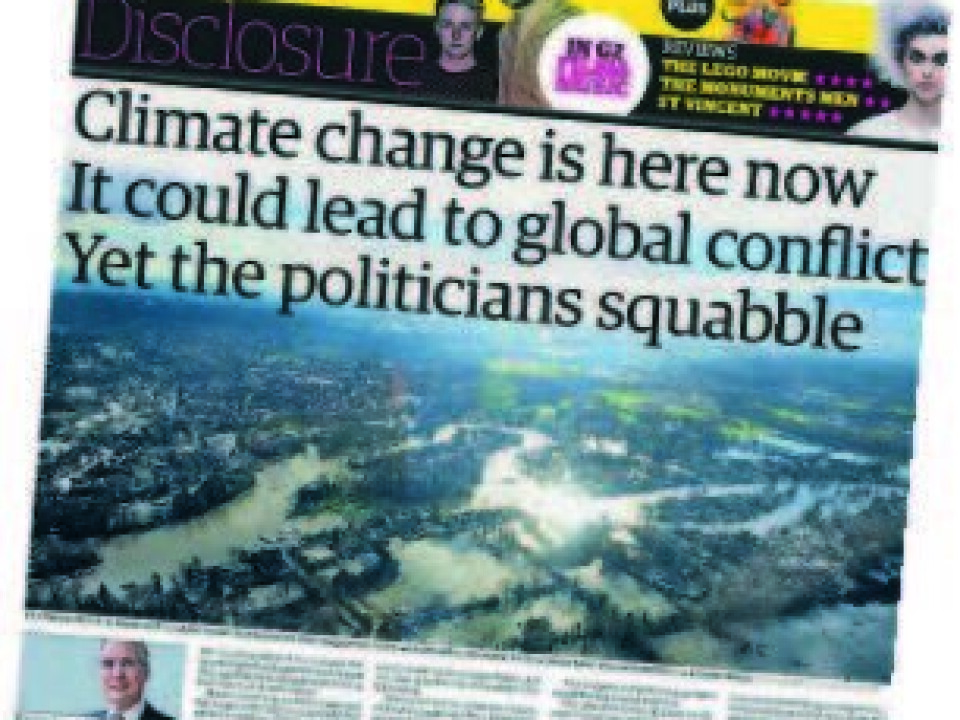

“The Guardian, for example, has taken a very clear position on climate change and it is therefore not particularly surprising that they are sceptical about climate engineering being a solution. Scientific American completely dismisses this approach to the problem. The Daily Mail has, for its part, a more ambivalent approach to climate change and climate research and often tries to present climate researchers as naive and foolish,” Dahl says.

Look for expressions of value

Dahl encourages the public to be more mindful when they read, and hopes to make people more aware of how text and language are framed and form a message.

Her most basic advice is to look for expressions of value that describe things as positive or negative, such as how “just”, “only” and “at best” were used regarding the duration of the climate initiative. In addition, one can look at how the pieces of information are put together and the comparisons that are made. The sources that are given a voice are also important. Is the person in question critical or positive towards this type of initiative?

“In general, it is wise to seek out multiple news sources so that the different angles can be seen in comparison with one another,” says Dahl and adds:

“Some groups, such as communications workers and politicians, know a great deal about these types of linguistic methods and actively use them. I believe knowledge about this could also be interesting and important for the general public when they develop opinions about difficult societal issues.”

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no